An Analysis of the Federal Voting Assistance Program and Recommendations for Improvement

Key Takeaways

« The Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP), created to help service members and U.S. citizens overseas vote in federal elections, has drifted far beyond its mission, expanding federal involvement while failing to engage its core constituents.

« Weak participation remains the underlying issue, showing that FVAP’s advancement of new technologies, pilot initiatives, and narrowly targeted outreach has not reduced barriers to voting.

« The program’s growing involvement in state-run election functions and promotion of insecure ballot methods have added complexity and risk while neglecting military voters.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) was established in 1986 to help service members, their families, and U.S. citizens overseas register to vote and cast ballots in federal elections. Nearly four decades later, many still face obstacles, reflected in persistently low participation rates that show that the program is not fully serving the people it was created to help.

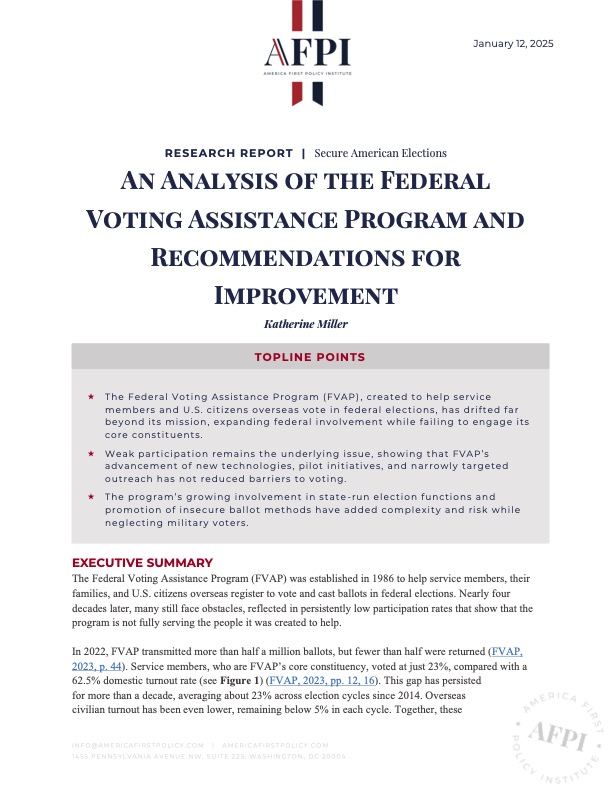

In 2022, FVAP transmitted more than half a million ballots, but fewer than half were returned (FVAP, 2023, p. 44). Service members, who are FVAP’s core constituency, voted at just 23%, compared with a 62.5% domestic turnout rate (see Figure 1) (FVAP, 2023, pp. 12, 16). This gap has persisted for more than a decade, averaging about 23% across election cycles since 2014. Overseas civilian turnout has been even lower, remaining below 5% in each cycle. Together, these figures indicate that FVAP has failed to increase participation among the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) voters (FVAP, 2015, p. 8; FVAP, 2023, p. 12).

Figure 1

Domestic and Overseas Voting Rates, 2022

Underlying these turnout disparities are procedural and logistical barriers that appear early in the voting process, such as registration confusion, varying state requirements, and mail delays that slow ballot transmission and return. These challenges are especially acute for service members, whose frequent relocations, limited access to reliable internet, and deployment schedules make it difficult to register, request ballots, and meet state registration and ballot return deadlines. Despite extensive investments in technology, outreach, and Voting Assistance Officer (VAO) training, FVAP’s strategies have not alleviated these obstacles due to three systemic weaknesses in its design and implementation.

First, the program does not meaningfully reach its intended audience. The Voting Assistance Ambassadors Pilot, for example, reached only 2,316 UOCAVA voters—78% of whom were civilians overseas (FVAP, 2023, p. 79). Although FVAP receives roughly $5 million in annual federal appropriations, its narrow reach among service members seems difficult to justify. The result is a costly initiative with minimal impact for those it was created to support.

Second, FVAP has drifted beyond its statutory mandate of providing voter assistance and education. By promoting DOW Common Access Cards (CACs) as digital signatures and funding ballot-tracking pilots with the U.S. Postal Service and private vendors, the program has introduced new federal processes into areas traditionally managed by the states (FVAP, 2023, pp. 76–81). These initiatives duplicate existing state systems, add unnecessary administrative layers, and divert limited resources that should be devoted to improving voter outreach and assistance for service members.

Third, the program continues to promote electronic ballot return despite warnings from federal security agencies—including the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Election Assistance Commission (EAC)—that such systems are “difficult, if not impossible” to secure (CISA et al., 2020, p. 2). Secure mail delivery, and other proven low-risk methods, such as the Federal Post Card Application (FPCA) and Federal Write-In Absentee Ballots (FWAB), remain the safest and most reliable options for absentee voting—methods from which FVAP has no reason to deviate.

To realign with its statutory purpose, FVAP must refocus on military voters, who have been overlooked due to the program’s emphasis on overseas civilians. It should also strengthen outreach and coordination with state election systems, uphold secure and auditable voting methods, and ensure transparent oversight of its funding and performance.

INTRODUCTION

FVAP is a DOW initiative established under the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Act (UOCAVA) of 1986. UOCAVA guarantees the right of service members, their families, and U.S. citizens residing overseas to register and cast absentee ballots in federal elections. UOCAVA delegates responsibility for carrying out this mandate to the Secretary of War, which is implemented through the FVAP Director, who, in turn, is responsible to the Under Secretary of War for Personnel and Readiness.

Over the past several decades, Congress has strengthened these UOCAVA protections through successive reforms. The Help America Vote Act of 2002 provided federal funds to states to modernize voting systems following the 2000 presidential election, when machine malfunctions, registration database errors, and ballot-design issues disrupted absentee voting. Followed by the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act of 2009, requiring states to send absentee ballots to UOCAVA voters at least 45 days before federal elections and authorized electronic delivery of registration and ballot materials to mitigate mail delays.

Despite these measures, absentee voters still experience challenges. As of 2022, FVAP officials estimated that approximately 2.8 million voting-age U.S. citizens lived abroad, yet fewer than half were aware of program services (FVAP, 2023, pp. 5, 39–40). Program officials attribute this communication gap to their frequent relocations and overseas assignments, but this shortfall more accurately reflects weaknesses in the program’s outreach structure and uneven support for Voting Assistance Officers. VAOs are typically unit-level military staff responsible for voter assistance alongside their regular duties but can also include civilian staff and independent contractors, including advocacy-aligned NGOs. Because these roles are part-time and rotate frequently, many VAOs lack the continuity and training needed to provide consistent guidance. As a result, service members often navigate the process independently, which helps explain why program participation continues to lag behind that of civilians.

These shortcomings point to a deeper management failure that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) identified as early as 2016 (GAO, 2016, pp. 28–31). The GAO found that FVAP lacked adequate data collection and analysis, clear implementation timelines, and defined performance measures for evaluating its initiatives. Although the program has since expanded its data collection through additional surveys and reports, it still lacks measurable benchmarks to assess progress or evaluate impact. Without such standards, participation is likely to remain stagnant, and federal funds will continue to be squandered at the expense of taxpayers and UOCAVA constituents.

FAILURE TO PRIORITIZE MILITARY VOTERS

These management failures the GAO identified have hindered FVAP’s ability to understand why participation among service members remains low. This has led the program to continue promoting standardized reforms shaped largely around how civilians vote, rather than the conditions military voters face, given their frequent relocation, deployment, and limited communication access in remote locations.

One of the clearest disparities lies in how ballots are transmitted. In 2022, 67% of overseas civilians received blank ballots electronically, compared with just 34% of active-duty personnel, who primarily receive ballots by mail because electronic delivery is often impractical in deployed settings (FVAP, 2023, p. 54). For deployed personnel, unreliable internet access, classified network restrictions, and limited power supplies make online ballot systems impractical for many field settings. Even when available, these systems introduce security risks that mail does not. Any breach involving deployed personnel could expose operational locations or identifying information—risks that far outweigh the marginal convenience of electronic ballot return. FVAP’s continued emphasis on digital systems ignores these realities, resulting in the same late arrivals and rejections that have long undermined military ballots, while introducing new cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

A similar imbalance is visible in FVAP’s Voting Assistance Officer (VAO) program. FVAP has increased the number of VAOs in Europe, where they mainly serve civilian populations, but has not made comparable investments in deployed or remote locations. As a result, many service members now lack direct, in-person support for ballot requests, verification, or troubleshooting—tasks that are essential in locations with limited or no connectivity. Roughly 7–10% of the active-duty force is deployed in forward or remote locations where internet and mail access are unreliable, making in-person assistance indispensable (DOD, 2024, p. 35). Without accessible VAOs, minor administrative issues can delay or invalidate ballots that otherwise could have been resolved on site immediately.

These coverage gaps also disproportionately affect younger and more mobile service members. FVAP’s 2022 Post-Election Survey of Active-Duty Military found that only 48% of service members aged 18-24 sought voting assistance, compared with 70% of those aged 25 and older. Across the services, members of the Navy and Air Force who sought help were significantly more likely to return their ballots successfully, while Marines were less likely to do so—evidence that VAO programs operate unevenly across branches and installations (FVAP, 2023, pp. 40–41).

Although assistance clearly improves outcomes when available, access to it continues to decline. In 2022, only about one-third of service members reported receiving help from a Unit or Installation VAO—down from nearly 60% in 2020—even though those who received any DOW assistance were almost five times as likely to return a ballot successfully (about 37%, compared with about 8% among those who did not)(FVAP, 2023, p. 40). While access has declined, the share of members who needed help but never sought it has risen compared to previous election cycles, showing that FVAP’s support network now reaches fewer voters even as its civilian outreach has grown, leaving service members—who most depend on it—with the least access to it.

FVAP has also extended services to civilian federal employees at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Public Health Service, even as long-standing issues for military voters remain unresolved. This pattern shows that the program lacks clear priorities, pursuing new responsibilities rather than strengthening the systems on which military voters depend.

PERSISTENT BARRIERS AND OPERATIONAL FAILURES

FVAP continues to launch new pilots, partnerships, and technology projects to modernize absentee voting. However, these efforts overlook the underlying problem: both overseas civilians and military voters still struggle to understand how to register, request, and return their ballots correctly.

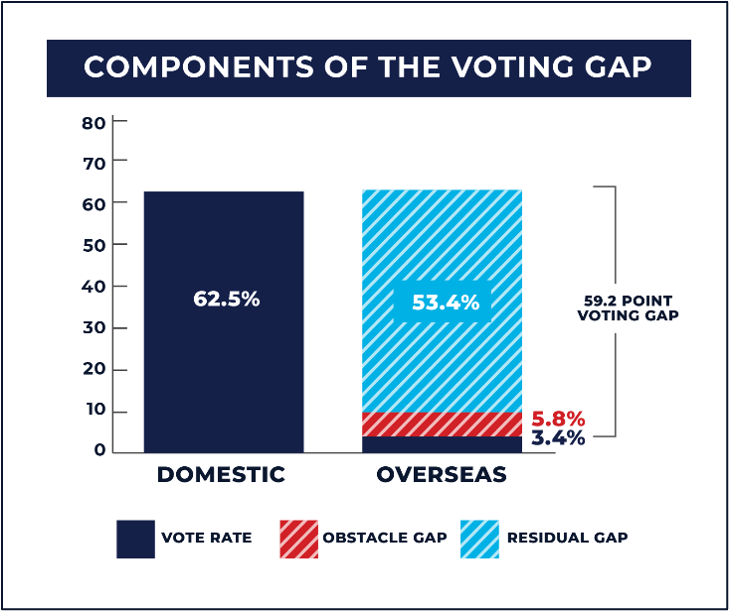

Survey data show that 21% of Americans abroad struggled to register, 22% had difficulty understanding the process, and 20% found it overly complicated (FVAP, 2023, p. 91). For younger overseas civilians aged 18–34, these procedural complications outweighed a lack of interest by as much as 19 times, indicating that confusion, rather than apathy, discourages participation.

Figure 2

Barriers to Ballot Return

Note.

Percentages are from FVAP’s 2022 OCPA (Question 17). Small differences may reflect rounding or how the results are summarized.

This confusion continues through every stage of absentee voting. In 2022, only 65% of U.S. citizens requested an absentee ballot—down from 91% in 2020, when expanded mail voting during the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily boosted participation (FVAP, 2023, pp. 38-39). Even after accounting for that surge, the 2022 rate still points to a breakdown in voter understanding: just over half (53%) expected to automatically receive a ballot, suggesting that many voters did not understand the need to request one. This misunderstanding remains a critical stumbling block to participation.

Registration among active-duty service members also lags behind that of civilians by about 11 percentage points, even after adjusting for demographics such as age, sex, and education (FVAP, 2023, p. 13). This shortfall reflects FVAP’s larger communication failure: many voters are not reached by its outreach at all, and for those who are, the information they receive is inconsistent or unclear. As a result, even when guidance reaches its audience, it fails to clarify the absentee voting process.

The 2022 FVAP Report to Congress documents a similar pattern. Of the 654,786 UOCAVA absentee ballots transmitted, just 267,403 were returned, and only 261,104 were counted—fewer than half of those sent. Although the median rejection rate was 1.4%, this seemingly low figure masks deeper issues, since it excludes the large share of ballots that were never returned at all. Most rejections stemmed from ballots arriving too late—60.1% of military ballots and 67.4% of civilian ballots missed the deadline—or from signature problems (22.1% of military rejections and 17.2% of civilian rejections) (FVAP, 2023, pp. 44–45). While FVAP has identified these surface-level causes, it offers no detailed plan to address them beyond what is already provided through general outreach and coordination, demonstrating again that, while the program has augmented its data collection, it means little if the information is not applied to practical reform.

The EAC reports a similar trend nationally. Of the more than 1.3 million UOCAVA ballots transmitted in 2024, only about two-thirds were returned, with fewer than 4% rejected. Notably, 70% of these ballots were transmitted to overseas civilians, revealing that participation gaps affect all UOCAVA voters, not only military personnel (EAC, 2025, p. iv).

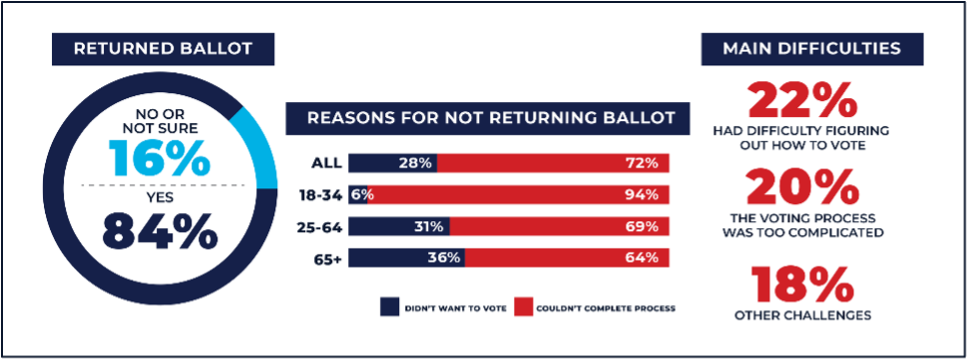

Regional data follow the same trend. Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Central America record higher obstacle gaps, yet Europe accounts for the largest number of “lost” votes—approximately 36,000 ballots that would have been cast if not for existing barriers (see Figure 3) (FVAP, 2023, pp. 27–28). The high volume of lost votes in this region, despite reliable mail service, again points to procedural confusion, rather than delivery delays, as the chief deterrent to participation. This is a fixable problem: FVAP can reallocate resources to strengthen VAO coverage on installations, revise training to clarify ballot procedures, and use regional metrics to track where ballots are delayed or lost. These changes will not solve every obstacle, but they can correct the basic procedural changes that discourage participation.

Figure 3

Estimated “Lost” Votes Due to Obstacles by Region, 2022

Taken together, this evidence shows that procedural complexity, rather than technology or logistics alone, remains the chief barrier to participation. Until FVAP delivers clearer guidance for all UOCAVA voters—especially stronger VAO support for service members and closer coordination with state election offices—they will continue to face the same procedural challenges, regardless of how many new pilots or tools the program introduces.

SECURITY RISKS AND INCREASED COSTS

FVAP continues to promote electronic ballot return as a solution for delivery and timing challenges, despite evidence that it improves neither and is, in fact, counterproductive to national security. Federal security agencies have repeatedly warned that it poses serious risks to election integrity.

For military voters in sensitive or remote locations with limited connectivity, electronic return offers little practical benefit while exposing ballots to additional privacy and security risks. One example is the agency’s email-to-fax service, which allows voters to submit ballots electronically. Between 2018 and 2022, its use grew by 122%, reaching nearly 3,500 transactions in the 2022 election cycle (FVAP, 2023, p. 66). Although this growth likely reflects greater awareness of the tool, it does not necessarily improve voting access, since it largely excludes deployed service members with limited connectivity and greater exposure to sensitive data leaks. Yet the agency promotes it as a uniform solution for all voters (FVAP, 2023, pp. 78–79).

The DHS, FBI, EAC, and NIST have cautioned that this system “creates significant security risks to the confidentiality of ballot and voter data, integrity of the voted ballot, and availability of the system,” adding, “We view electronic ballot return as high risk” (CISA et al., 2020, p. 2). Given such strong warnings, FVAP should take a more cautious approach to ballot reforms and ensure that any updates fully comply with the highest security standards.

Even so, data show that the electronic ballot return process itself achieved the results FVAP anticipated. Nearly half of electronically returned ballots were submitted in the final week before Election Day, increasing rejection risks and undermining the agency’s claim that electronic return resolves timing issues (FVAP, 2023, p. 56). This pattern suggests that late submissions stem more from voter uncertainty than transmission delays, confirming that technology alone cannot overcome the main barriers to participation.

Electronic returns also create additional burdens and costs for state election officials. According to the 2022 Post-Election Survey of State Election Officials, 79% of states accepted electronically returned ballots submitted without the inner “secrecy” envelopes used to protect voter confidentiality, and 63% of states processed FWABs as valid ballots (FVAP, 2023, PEVS-SEO, pp. 28–29). By accepting ballots without secrecy envelopes and processing FWABs as valid, states preserved ballots that otherwise would have been rejected but required labor-intensive workarounds, such as duplicating faxed or emailed submissions onto scannable paper, maintaining separate IT systems, and introducing new procedures that varied by jurisdiction. All of these accommodations place significant demands on staff time and equipment, requiring additional oversight and ultimately adding administrative complexity and driving up costs.

Without consistent procedures, states operate under fragmented standards for ballot management, which lengthen processing times, raise expenses, and weaken chain-of-custody safeguards—all of which threaten election integrity. These inefficiencies not only burden state election officials but also undercut FVAP’s assertion that electronic systems encourage participation. In reality, their complexity discourages it.

Moreover, these systems are used only by a minority of voters. FVAP’s own data show that even among overseas citizens who had the option to use electronic ballot return, more than 40% of voters opted not to, instead preferring mail—the method used by 56% of Americans abroad in 2022 (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, pp. 31, 40–41). This trend, based on post-pandemic election results, suggests that the limited use of electronic return reflects genuine voter preference rather than temporary COVID-era circumstances. Therefore, the program should realign with users’ favoring secure mail, rather than supporting a system that serves a small minority at the expense of most voters.

FEDERAL OVERREACH INTO STATE-RUN ELECTIONS

Despite these demonstrated risks and minimal benefits, FVAP has continued to expand federal initiatives—such as ballot-tracking pilots and digital-signature programs—that introduce new layers into state-run election systems.

In recent years, FVAP has overstepped into areas traditionally left to the states. In its 2022 Report to Congress, the program pledged to “aggressively engage” with state and local election officials by promoting Common Access Cards (CACs) as digital signatures and funding ballot-tracking pilots with the U.S. Postal Service, the Military Postal Service Agency, the State Department, and with private vendors (FVAP, 2023, pp. 7, 76–81). While framed as a way to streamline ballot delivery, these initiatives duplicate existing state processes and pressure local officials to adopt new procedures or share voter data that has long been managed at the state level.

By promoting CACs as digital signatures, FVAP pressures states to modify their voter-verification systems to align with federal forms of identification—not to strengthen verification standards, but to impose a federal model on a process already governed at the state level. Its ballot-tracking pilots add redundant scanning steps and new inter-agency systems that disrupt state-managed chain-of-custody procedures. Yet, responsibilities such as setting election timelines and procedures, maintaining voter-registration databases, and enforcing voter-verification have long fallen under the authority of the states (U.S. Const. art. I, § 4; Help America Vote Act of 2002; National Voter Registration Act of 1993). The result is unnecessary complexity, where additional vendor contracts, multiple scanning points, and mismatched systems increase the risk of lost ballots, inaccurate tracking, or delayed delivery—all without demonstrable gains in reliability. Through such actions, FVAP has exceeded its statutory mandate of providing voter assistance and education, complicating ballot processing, and setting a troubling precedent for expanding federal influence over state-run elections.

Equally troubling is the lack of coordination across FVAP’s initiatives. A 2021 Inspector General review found that FVAP had not established formal agreements (such as memorandums of understanding) with partner agencies, including the Department of Justice, DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or state election offices, to guide collaboration or implementation (DOD OIG, 2021; DOD OIG, 2025). Two years later, FVAP has yet to adopt these recommendations, a failure that constitutes a serious lapse in oversight given the program’s continued launch of new projects.

State election officials likewise report limited value in coordinating with FVAP. Survey data show that 69% of officials did not refer colleagues to its training programs because comparable resources already existed, and fewer than one in three used its policy papers or reports (FVAP, 2023, PEVS-SEO, pp. 14–16). These responses suggest that the program’s mission creep has made it less useful to its intended state and local partners.

These concerns have been raised by state officials. In Montana et al. v. Biden et al. (D. Kan., filed Aug. 13, 2024), nine state attorneys general argued that Executive Order 14019 “swamps state regulatory authority” and “undermines the regulatory structures Plaintiff States have created,” by forcing states to manage new federal voter-registration programs, adjust their procedures to federal schedules, and divert limited resources to federal oversight (Montana et al. v. Biden et al., 2024, ¶¶ 143–144). This case illustrates how federal “assistance” can and has quickly evolved into administrative overreach.

RISKS OF BIASED AND INEFFECTIVE OUTREACH

Parallel to these federal expansions, FVAP’s public-facing communication strategy has shifted toward behavior-based digital outreach, raising further concerns about neutrality and effectiveness.

FVAP has increasingly relied on data-driven campaigns, using “behavior-based” strategies, paid media, and mass email communications that together generated more than half of FVAP.gov’s traffic during the 2022 cycle (FVAP, 2023, pp. 67–68, 80). Built around the habits of younger, higher-educated civilians who are most active online, this strategy has failed to engage that audience and done even less for service members, who need more direct support, as previously highlighted. The issue lies not only in the program’s reliance on digital outreach but also in its messaging design. It targets a narrow segment of overseas civilians whose demographics skew liberal, and it offers voters little in the way of clear or practical guidance. As a result, the program struggles to reach many groups effectively, thus leaving service members with less online access and support. This limited approach also risks creating the perception of political bias, given its significant focus on a single voter profile that does not represent the broader UOCAVA population.

Demographic data reinforces this concern. Americans abroad are disproportionately well-educated, with 68% holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 34% domestically. They are also younger, with only 9% aged 65 or older, compared to 22% above 65 domestically (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, p. 12). Among those who requested ballots that year, nearly four in five held at least a bachelor’s degree, almost half reported household incomes above $75,000, and the median age was 49 (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, pp. 36–37). These findings show that FVAP’s outreach targets those who should be the easiest to reach online, yet their participation among them remains low. This suggests the main barrier is not technology but the quality and clarity of the program’s communication. For military voters—especially enlisted military personnel, who comprise more than 80% of the active-duty force—these weaknesses are even more consequential, making them more dependent upon direct assistance from VAOs rather than online engagement (DOD, 2024, pp. 18–19).

FVAP’s outreach focus also overlaps with groups actively targeted by political campaigns, which deepens the perception of bias. In 2022, 12% of U.S. citizens abroad received absentee voting information directly from political parties or candidates—slightly below 13% in 2020, when COVID-related outreach temporarily expanded digital campaigning, but well above 8% recorded in 2016 and in 2018 (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, pp. 38–39, 44-45). While comparable data for domestic absentee voters are not collected at the federal level, this trend shows that overseas voters have become a consistent target for partisan outreach. As FVAP continues to direct its own messaging toward this same group, the distinction between nonpartisan voter assistance and political campaigning becomes harder to maintain. When a federal program’s audience mirrors that of political actors, public confidence in its neutrality inevitably erodes.

This risk is reflected in FVAP’s own outreach materials, which now resemble activist-style voter registration drives rather than neutral government guidance. In 2022, the agency distributed more than 172,000 informational kits, posters, and workshop materials across 41 countries and 105 installations (FVAP, 2023, pp. 72–73). One poster juxtaposed “how overseas citizens grocery shop” with “how they vote,” using casual slogans and lifestyle imagery more typical of commercial advertising than official instruction (see Images 1 and 2) (FVAP, 2024, Election Outreach Toolkit). Such messaging risks trivializing the act of voting and endorsing civilian experiences over military realities. In doing so, FVAP alienates the very service members the program was designed to support—a disconnect that helps explain why these campaigns have failed to build trust or improve engagement.

Image 1. FVAP overseas outreach graphic. |

Image 2. FVAP overseas outreach graphic. |

Image 1. FVAP overseas outreach graphic.

Image 2. FVAP overseas outreach graphic.

Even with this new style of approach and expanded digital campaigns, the program achieved no meaningful gains in voter awareness or participation. Only 39% of Americans overseas were aware of FVAP during the 2022 election cycle; just one in three saw any FVAP election messaging; and only 14% recalled its most recognizable advertisement. Voting outcomes reflect the same shortfall: two-thirds of respondents said they voted, but state records verified only about 53% as having an accepted and counted ballot—well below the domestic voting rate of 62.5% (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, pp. 41-42). These results show that FVAP’s emphasis on lifestyle branding over clear instruction has not improved engagement or recognition among voters. Rather than simplifying the process, the program continues to complicate itself with unnecessary marketing and design choices that dilute its core purpose: helping voters understand how to cast a ballot successfully.

FVAP’s official guidance materials reinforce the same communication problems seen in its outreach. The Voting Assistance Guide, published biennially by the Office of the Under Secretary of War for Personnel and Readiness, instructs voters to file a new FPCA each year and allows FWABs to be completed by naming either a candidate or a political party. FVAP’s accompanying policy briefs also highlight the program’s encouragement of states to broaden voting access by expanding eligibility for “never-resided” voters who have never lived in the United States but could vote in a parent’s last state of residence, and by extending automatic voter registration (FVAP, 2016; FVAP, 2017). These policies, which are widely perceived as characteristic of Democratic-led states, reinforce perceptions of partisanship and add to the program’s pattern of blurred neutrality.

The use of FVAP’s digital tools shows a similar pattern of diminishing trust. In 2022, 55% of U.S. citizens overseas—drawn from the program’s own respondent pool of voters already aware of the absentee process—reported visiting FVAP.gov at least once, down from 72% in 2020. Only 10% used the Online Assistant Tool, compared with 41% in 2020 and 33% in 2018. Because these figures represent self-reported awareness rather than unique site users, they indicate shrinking engagement among FVAP’s most active audience. By contrast, larger shares relied on international media (54%), general web searches (49%), or state and local election sources (41%) (FVAP, 2023, OCPA, pp. 43–44). This continued shift away from FVAP’s official resources underscores a larger credibility problem: voters no longer view the program as a clear or trusted authority on the absentee voting process.

Taken together, these findings point to a steady decline in FVAP’s effectiveness. As its communications have grown more complex, they have become less practical, focusing heavily on image, policy expansion, and experimentation instead of clarity. In a highly polarized online environment, this confusion has tangible consequences: when official information feels politicized or inconsistent, voters turn to informal or partisan sources, which compounds misinformation issues and further undermines trust in absentee voting. Each layer of unclear communication also increases the burden on VAOs and state election officials, who must correct or clarify information that FVAP should have provided clearly in the first place. To restore confidence, the program must return to its statutory role: providing simple, neutral, and consistent instructions that help all voters easily and successfully cast their ballots.

Recent expansions and credibility failures, coupled with the structural and operational weaknesses detailed above, underscore the need for specific policy reforms to restore FVAP’s neutrality, accountability, and focus.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Congressional Actions

- Establish budget transparency requirements for FVAP appropriations, requiring annual disclosure of how funds are divided between military and civilian support activities.

- Mandate measurable performance benchmarks for military registration and ballot-return rates, tying future funding increases to demonstrated improvement.

- Phase out electronic ballot return and restore reliance on secure, auditable mail-based systems (FPCA and FWAB), which remain the most widely used methods globally and are endorsed by federal security agencies as safer than electronic return. Strengthen mail delivery timelines, tracking, and contingency tools rather than expanding high-risk digital return systems.

- Implement stricter identity verification for absentee voters (particularly those who have never resided in the United States) and crack down on vulnerabilities in electronic or mail-in absentee voting.

- Disclose all NGO expenditures by name, amount, and purpose of grants or other payments regarding federal voting assistance during the 2024 election cycle.

- Codify FVAP’s limited statutory mandate to reaffirm that its role is to facilitate, not administer, absentee voting and to preserve state authority over registration, verification, and counting.

Department of War Actions

- Reallocate VAO resources available to strengthen cybersecurity, protect voter data, uphold state-based verification standards for overseas ballots—without adopting CACs or other federal digital ID systems—as part of a secure, auditable mail-based process for active-duty service members.

- Audit and revise VAO training and public-facing materials to ensure strict neutrality, legal compliance, and clarity focused solely on absentee voting procedures.

- Ensure that non-military VAOs meet clear, uniform training and neutrality requirements, excluding politically aligned or advocacy-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs) from any staffing or training functions.

- Require the DOW to assess awareness of UOCAVA rights among active-duty personnel through secure, anonymized reporting mechanisms that protect operational security.

- Ensure future FVAP resource allocations prioritize military and dependent voters while maintaining statutory service for overseas civilians under UOCAVA, to correct current imbalances.

- Review all third-party and NGO agreements to ensure FVAP contractors do not engage in voter registration or advocacy inconsistent with FVAP’s neutral mission.

FVAP Internal Administrative Action

- Require FVAP to publish standardized performance metrics—covering registration, ballot transmission, and return rates—disaggregated by service branch and overseas region in each biennial report to Congress, thus enabling measurable oversight of participation trends and resource effectiveness.

- Audit all FVAP grants and, where permitted by law, redirect or rescind funding that does not directly support UOCAVA voters—especially active-duty service members—or strengthen election integrity.

- Strengthen partnerships with state election officials to ensure resources promote election integrity, state-led UOCAVA compliance, and limited federal interference

Inspector General Oversigh

- Require the DOW Inspector General to conduct biennial, independent audits of FVAP’s budget, grantmaking, and program outcomes, with findings publicly reported to Congress and summarized in FVAP’s biennial Report to Congress.

PROBLEM-POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The table below summarizes the report’s eight core problems and their corresponding policy solutions.

Problem |

Policy Solution |

Mission Creep and Federal Overreach: FVAP has moved into state election functions via CAC promotion and ballot-tracking pilots—activities the GAO and DOW IG found exceeded its mandate. |

Codify FVAP’s limited mandate to reaffirm its facilitative role. End CAC-based and digital-signature programs and require compliance with state verification standards to preserve state control. |

Limited Coordination with States: FVAP duplicates existing state programs and lacks formal implementation agreements with state and federal partners. 69% of state officials report little to no use for its training resources. |

Establish formal coordination agreements (MOUs) with state and federal partners. Streamline training and data-sharing to eliminate duplication and to support consistent UOCAVA compliance. |

Persistent Ballot Rejections: Of 654,786 ballots transmitted in 2022, fewer than half were returned; 60% arrived late; and 22% were rejected for signature errors (FVAP, 2023). |

Refocus VAOs on resolving mail delays and signature issues. Set performance benchmarks for registration and ballot-return rates, tying funding to measurable improvement. |

Electronic Ballot Return Is Insecure: DHS, FBI, NIST, and EAC (2020) warned that electronic ballot return is “difficult, if not impossible, to secure,” yet FVAP continues to promote it. |

Phase out electronic ballot return and restore reliance on secure, auditable mail-based systems (e.g., FPCA and FWAB). Require DOW IG cybersecurity review of any technology pilots. |

Declining Awareness of Tools: Awareness of FWAB fell from 38% in 2020 to 17% in 2022, and FPCA awareness dropped to 29%. |

Simplify VAO training and outreach with clear FPCA/FWAB instructions. Publish standardized metrics in biennial reports and expand VAO coverage where awareness is lowest. |

Civilian Over-Prioritization: In 2022, roughly 77% of FPCA submissions came from civilians, while only about 21% came from service members (FVAP, 2023). |

Reallocate VAO resources to deployed and remote units. Prioritize trained service members in VAO roles and require budget transparency between military and civilian activities. |

Excessive NGO and Vendor Reliance: FVAP funds external groups with limited transparency and unclear outcomes. |

Audit and disclose all grants and contracts by name, amount, and purpose. Exclude advocacy groups from staffing or training roles and redirect funds to direct military support. |

Weak Accountability and Oversight: GAO and DOW IG found that FVAP lacked performance benchmarks and budget transparency across its $5 million appropriation. |

Mandate biennial independent IG audits with results to Congress. Require annual budget reports and strengthen ID-verification standards to improve integrity and oversight. |

CONCLUSION

FVAP’s steady trend toward expansion has eclipsed the simplicity the program was meant to preserve, and what allows it to function best. The program has tried to “innovate” through new pilots, partnerships, and technology initiatives, but these have only added complexity and produced negligible change in how easily service members can register and return their ballots. FVAP continues to collect detailed data through additional surveys and reports, but this information has clearly not informed the program’s design approach to solving these problems, as shown by persistently low turnout among all UOCAVA voters for more than a decade. To be effective, FVAP must return to the essentials: clear registration guidance, greater institutional support for VAOs, and coordination with state election offices to ensure ballots are reliably received and counted. Overseas citizens and service members deserve a program that puts their needs first to ensure the voting process is simple and easy to navigate—not one that tries to do more than it was created to.

Works Cited