Supporting the Emerging Civil Rights State

Key Takeaways

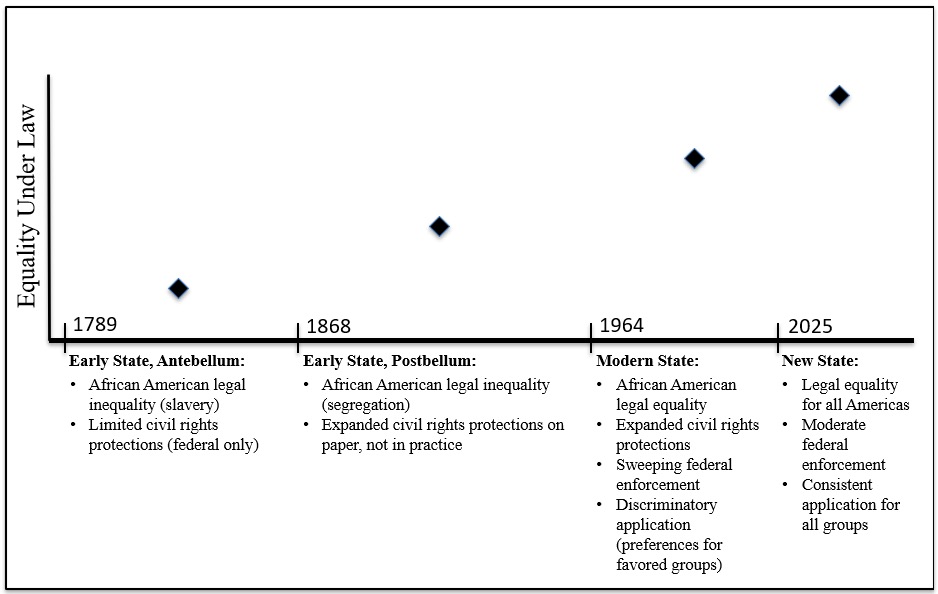

« The United States’ civil rights enforcement apparatus or “state” underwent a profound transformation during the mid-1960s. The resulting “modern” civil rights state expanded civil rights protections overall but also reduced them in important respects.

« The Trump Administration is closing these gaps by using its civil rights enforcement authorities to eliminate institutionalized equity-based discrimination.

« In doing so, the Administration is laying the foundations for yet another civil rights state, one that will finally dispense with both de jure and de facto discrimination and guarantee equal treatment under law for all Americans.

Introduction

A defining feature of the second Trump Administration has been the stunning pace and scope of its policy reform agenda. Yet, even against this backdrop, recent changes to civil rights enforcement stand apart. Properly understood, these changes form the foundations for a new civil rights state.

This process of state transformation is eliminating previously tolerated—and, in some cases, mandated—discrimination from American public life. This is most evident at elite universities where the Administration’s Title VI enforcement is extending civil rights protections to members of previously excluded groups. This includes so-called “majority groups” (i.e., whites) facing discrimination under the guise of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies; Jewish Americans facing harassment, intimidation, and violence; and Asian Americans facing discrimination in college admissions. Other divisive agendas linked to misapplied civil rights statutes (e.g., transgender policies) are similarly being rooted out.

Paradoxically, the legal basis for dramatically revamping civil rights enforcement is found in the text of existing civil rights law. Given longstanding institutionalized racial discrimination under the guise of affirmative action—and more recently, DEI—it is easy to imagine that U.S. constitutional and/or statutory law recognizes special classes of Americans: some of whom possess and others of whom lack civil rights protections. Though this situation existed in effect for six decades, it was never lawful.

This report explores the Trump Administration’s transformative civil rights agenda, situating recent changes in a broader historical context. It argues that the emerging civil rights state is poised to transform American politics and political culture. Finally, this report aims to spur new research and activism to advance the cause of equality under law for all Americans.

America’s Early and Modern Civil Rights States

The U.S. political system differs in practice from the system described by the U.S. Constitution. That document created a new national entity, the federal government, by assuming a list of powers from state governments. Federal power was further limited by the Bill of Rights, a list of civil liberties and civil rights protections.[1]

Following the passage of the 14th Amendment, the jurisdiction of the Bill of Rights expanded to encompass state governments. On paper, incorporating the Bill of Rights substantially altered the political order; however, in practice, the civil rights and liberties of the American people changed little during this period. This is because newly expanded protections for civil rights and liberties were roundly ignored in the American South. The same was true for new voting (civil) rights protections added by the 15th Amendment.

By the mid-20th century, this situation had become untenable. The “early” civil rights state, characterized de facto legal inequality for African Americans, came under immense public pressure for reform. Before the Civil Rights Movement concluded, that state had transformed into a new entity. The “modern” civil rights state sought to purge American society of racial discrimination against members of historically discriminated against (now government favored) groups, and to achieve broad social equality for members of all groups.

To this end, the federal government assumed sweeping new powers to prohibit discrimination in employment, education, public accommodations, housing, and voting.[2] To remedy the effects of past discrimination and still worse forms of oppression (slavery), the federal government additionally imposed racial hiring preferences (“affirmative action”) internally and for recipients of federal contracts (Johnson, 1965). Due to the broad scope of federal reach and ambiguities in the enforcement of civil rights law, affirmative action, like antidiscrimination law, became a de facto nationwide mandate in employment and education (Hananiah, 2023).

The effects of the civil rights state transformation extended to even the constitutional structure of the American political order. The Civil Rights Act (CRA, 1964) effectively revoked the 1st Amendment’s free association clause where businesses serving the public were concerned (Epstein, 2014). Conversely, the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause was resurrected during this period to dismantle Jim Crow—yet this same clause was simultaneously reburied for racial majorities through discriminatory affirmative action policies, and through various racial set-asides and preferences such as scholarships and business loans (La Noue, 2025). This inconsistency was no less apparent to the nation’s courts as to its mass public; however, the Supreme Court allowed these policies to continue, for a time, in the hopes of ameliorating the nation’s deep racial wounds (Grutter v. Bollinger, 2003).

Without question, the most fundamental change initiated by the modern civil rights state was the institutionalization of large-scale federal monitoring and enforcement of social values throughout the public sphere of American life. This was a power never intended by the Framers and one they would have unquestionably regarded as tyrannical. The U.S. political system had been carefully crafted to avoid the accumulation of total power by the federal government—something the modern civil rights state came close to attaining.[3]

The Unwritten Constitution of the Modern Civil Rights State

Under the early civil rights state, civil rights enforcement never approached its constitutional or statutory limits. Conversely, under the modern civil rights state, those limits were breached almost immediately. Consider the case of so-called “disparate impact discrimination,” the notion that neutral policies—those making no distinctions between members of groups—can be regarded as “discriminatory” if they adversely impact members of some groups vis-à-vis others, on average (Legal Dictionary, 2016).

Disparate impact theory has been a potent tool for federal agencies and courts to expand their reach into state and local governments, and the private sector. Prominent examples include:

- Restricting employment aptitude tests, including written exams and physical fitness tests (Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 1971; Bushey v. New York Civil Service Commission, 1984; United States v. City of Erie, Pa., 2025).

- Restricting the use of criminal background checks in employment and housing (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. BMW, 2013; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2016).

- Forcing K-12 schools to reduce discipline standards for black students relative to white students (Lhamon & Samuels, 2014).

Of course, equal treatment almost necessarily results in disparate outcomes. The reason is simple: no natural law provides for the random distribution of talents, interests, and habits across whatever identity categories happen to be of particular interest to government bureaucrats and judges. Consequently, disparate impact analysis has no obvious limiting principle. Taking disparate impact seriously, is it not “racist” to require a bachelor’s degree as a condition of employment or for admission to graduate school (McElrath & Martin, 2021)? What about punishing crime? Surely enforcing laws must be racist as well as sexist, given measurable disparities in the commission of crimes including illegal drug use, theft, assault, and murder, just to name a few (FBI Crime Data Explorer, n.d.).

In wielding these expansive and intrusive powers, courts and federal agencies claimed authorities provided by Civil Rights Act, yet the phrase “disparate impact” is nowhere to be found in that statute. More importantly, the plain language of the Civil Rights Act explicitly rejects the rationale on which disparate impact theory rests. In Title VII, the law states,

Nothing contained in this [law] shall be interpreted to require any employer, employment agency, labor organization, or joint labor-management committee subject to this [law] to grant preferential treatment to any individual or to any group because of the race, color, religion, sex, or national origin of such individual or group on account of an imbalance which may exist with respect to the total number or percentage of persons of any race, color, religion, sex, or national origin employed…in comparison with the total number or percentage of persons of such race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in any community, State, section, or other area, or in the available work force in any community, State, section, or other area. (CRA, 1964, Title VII, p. 16)

Prior to 1991, a plain reading of civil rights law should have prohibited rather than abetted the use of disparate impact analysis. In effect, disparate impact law existed entirely within what could be called the “unwritten constitution” of the modern civil rights state: an informal understanding that constitutional and statutory guarantees of legal equality can and should be set aside to advance the higher imperative of leveling group disparities.

During this period, and still today, the unwritten constitution manifested in inconsistencies in the use of the word “discrimination.” According to Webster’s Dictionary, “discrimination” describes both “distinguishing, or noting and marking differences” and “unfair treatment of a person or group on the basis of prejudice” (Webster, 1913). Similarly, Wordnet dictionary describes discrimination as both “the cognitive process whereby two or more stimuli are distinguished” and “unfair treatment of a person or group on the basis of prejudice” (Open English Wordnet, 2020).

It follows that racial discrimination describes choosing or distinguishing between people based on a racial category distinction—a practice with a well-earned negative connotation (hence the descriptor “unfair”). Yet, oddly, choosing between college or job applicants based on racial category distinctions was not publicly (or legally) understood to constitute racial discrimination during this period (Burgess, 2020). At best, such practices might have been referred to as “reverse discrimination”—a strange term that suggests discrimination against certain groups is not true discrimination (Smith, 2025).

The fact that such conventions were themselves discriminatory was irrelevant. Employers rarely needed to consider how a given hiring or promotion policy might disproportionately disadvantage members of government-disfavored groups, such as whites, males, or heterosexuals. It was widely understood that the federal agencies, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Justice Office for Civil Rights, would never demand accounting for such practices.[4] By contrast, policies adversely impacting members of government favored groups—e.g., blacks, women, and homosexuals—risked attracting ruinous federal attention (Hananiah, 2023).

Another characteristic of the modern civil rights state was the tendency to pay lip service to its stated (i.e., textual) goals while simultaneously pursuing its unwritten goals. This “doublespeak” was present almost from the modern civil rights state’s beginnings. For example, Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 executive order (EO) created nationwide affirmative action policies (“disparate treatment”) while also prohibiting racial discrimination. The order states,

It is the policy of the Government of the United States to provide equal opportunity in Federal employment for all qualified persons, to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin… (1) The contractor will not discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin. The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin…The contractor will, in all solicitations or advertisements for employees placed by or on behalf of the contractor, state that all qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, creed, color, or national origin. (Johnson, 1965; italics added)

Similarly, defenders of affirmative action have long argued against reading the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause in a straightforward way. The clause reads,

… No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. (U.S. Const. amend. XIV, 1868; italics added)

Noting that the amendment was enacted to protect members of a marginalized group (freed slaves), affirmative action proponents assert the 14th Amendment confers no similar protections to members of “majority” groups. However, the text itself references only “citizens of the United States” and “any person(s).” It says nothing about majorities or minorities.

To assert that these abuses and linguistic absurdities derive from an unwritten constitution is to emphasize their absence of statutory or constitutional justification. This is generally accurate, albeit with one qualification. Following several court decisions that narrowed the application of disparate impact law, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1991, thereby codifying disparate impact law for employment discrimination cases (CRA, 1991). This retroactive justification notwithstanding, disparate impact theory derives from the same premise that animate government-mandated racial discrimination, linguistic absurdities, and double standards under the modern civil rights state: the idea that formal legal equality may be set aside to advance equity.

When considered alongside America’s constitution, founding principles, the bulk of its civil rights law, and the values of its people, the unwritten constitution appears to have always been an anomalous, rogue element in the U.S. political system. Its embrace of doublespeak, its circumvention of statutory limitations, and its rejection of equal treatment under law are all in tension with core American values and traditions. The unwritten constitution took root, in large part, due to the American public’s fervent desire to redress past wrongs. However well-meaning, it must be recognized that the function of the unwritten constitution has been to undermine equality under law.

Politics in the Modern Civil Rights State

The early-to-modern transformation of the American civil rights state coincided with a similarly dramatic transformation of the world’s oldest political party: the Democratic Party. Formed in the 1820s from the dissolution of the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans, the Democratic Party was long associated with defending the institution of slavery. Following the Civil War, Democrats again targeted African Americans for unequal treatment through a host of new discriminatory “Jim Crow” laws.

Democrats’ embrace of African American legal inequality continued well into the Civil Rights Era. During this period, segregationist lawmakers and voters were overwhelmingly Democrats (Karol, 2009). It was Republican lawmakers who provided most votes for the Civil Rights Act (1964), overcoming a 75-day Democratic filibuster in the Senate (Swain, 2017).

At the same time, the two parties’ civil rights positions were somewhat muddled. Consider the candidates for the 1964 presidential election. President Lyndon Johnson had shepherded the Civil Rights Act into law, yet he had also begun his political career campaigning for anti-lynching laws—a high watermark for postbellum racism in American politics (Selby, 2014). The liberal civil rights lion would also frequently refer to his own sweeping civil rights legislation using the “n-word” (Howard, 2014). By contrast, Barry Goldwater had opposed the Civil Rights Act, citing (as it turned out, prescient) concerns regarding its expansion of federal power. Yet Goldwater had previously supported civil rights bills in 1957 and 1960; had personally led efforts to desegregate Arizona’s National Guard and the U.S. Senate cafeteria; and had been an early member of the Phoenix chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Urban League (Edwards, 2014; Whittaker, 2005).

Another complicating factor during this period was the meaning of the term “conservative.” As today, the Republican Party (GOP) was then regarded as the more conservative of the two parties, on both social and economic issues; however, the Democratic Party remained the ancestral home of what could be called “racial conservatism.” The GOP had made steady gains with white southerners beginning almost immediately after the end of the Civil War, yet it remained “pro-civil rights” in the context of postbellum politics and in relation to the Democratic Party (Trende, 2012).

The degree to which the partisan realignment of the South represented the Republican Party absorbing the Democratic Party’s newly jettisoned segregationist sentiments remains contentious.[5] What can be said with a high degree of confidence is that the Democratic Party underwent a more dramatic change during this period than the GOP. In effect, the modern Democratic Party revamped itself by appropriating the Civil Rights Movement as its own “brand.” This turn was reflected in the party’s embrace of “identity politics:” the uniting of “race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, and any other number of identitarian categories with a politics of victimization” (Azerrad, 2019, p. 2). Through rhetorical and even performative reenactments of the Civil Rights Movement—e.g., retracing historic civil rights marches— elected Democrats and progressive activists harnessed old, as well as new, identity-based grievances against American society for political gain (The Hill, 2023; Klein, 2020; Southern Poverty Law Center, 2012; The Hill, 2023; Klein, 2020).

The centrality of the Civil Rights Movement to the present-day Democratic Party helps to account for why its leaders now seem compelled to take so many wildly unpopular positions. Recent prominent examples include:

- Opposing deportation of criminal illegal aliens—a policy supported by 57% of Americans (AFPI Messaging and Data Lab, 2025).

- Defending male participation in women’s sports—a policy opposed by 75% of Americans (Francis, 2025).

- Supporting sex-change surgeries and hormone therapies for minor children—procedures opposed by 71% of Americans (Lynch, 2025).

- Supporting open borders—70% of Americans disapproved of President Biden’s handling of immigration in January of 2024 (Arthur, 2024).

- Supporting dismantling police departments—84% of Americans support increasing (47%) or maintaining (37%) existing spending on police in their area (Parker & Hurst, 2021). Additionally, 75% of Americans describe “the defunding of police departments” as “a reason that violent crime is increasing in the United States” (Harper, 2022).

In each case, the interests of members of supposedly “marginalized” groups conflict with those of the wider society. To characterize the provision of sex-change hormones to minor children or abolishing national sovereignty as outgrowths of the struggle for African American equality is to view the Civil Rights Movement through a distorted lens. Yet such connections are routinely asserted by elected Democrats, advocates, and interest groups (Buncombe, 2017; Congressional Progressive Caucus Center, 2025; Southern Poverty Law Center, 2012; Redmon, 2011).

Indeed, prominent civil rights organizations, including those with deep ties to the Civil Rights Movement, function as de facto arms of the Democratic Party, even to the exclusion of their stated missions. For example, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) was formerly committed to defending the free speech rights of all Americans, no matter how repugnant the speech—the organization famously defended the Ku Klux Klan’s speech rights in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). However, in 2017, as the Democratic Party warmed to online censorship following the election of President Trump, the ACLU abandoned their historic commitments, reasoning, “Speech that denigrates (marginalized) groups can inflict serious harms and is intended to and often will impede progress toward equality” (Kaminer, 2018; ACLU, 2017). The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a group with a storied history of battling the Ku Klux Klan in court, lists mainstream conservative organizations and figures as “extremists” alongside neo-Nazis and paramilitary organizations (SPLC, 2025).[6] Likewise, the Anti-Defamation League’s (ADL) efforts to combat antisemitism are clearly bound by its higher commitment to progressive politics (Menken, 2024).

In the parlance of political science, the civil rights issue has been “owned” by the Democratic Party in recent decades—i.e., voters have generally held favorably views of Democrats’ positions on civil rights issues (Petrocik, 1996).[7] Issue ownership matters insofar as when public attention shifts to (or is shifted to) owned issues, the owning party tends to benefit politically.

At the same time, owned issues can be “stolen” by the opposing party. For example, the Democratic Party historically owned education; however, Republicans contested this claim in recent decades by emphasizing broadly popular positions on school choice, accountability, and parental rights (Egan, 2013; Davis, 2016). Today, public opinion is generally more favorable towards the Republican Party than towards the Democratic Party on education policy (Malkus, 2022).

Given the moral weight of the Civil Rights Movement and Democrats’ close association with it, Republicans spent the last half century largely trying to avoid the issue. Following Goldwater’s historic loss in 1964, Republican presidents repeatedly passed on opportunities to reverse civil rights state expansions by their Democratic predecessors. For example, no Republican president—from President Nixon all the way to President Trump’s first term—revoked President Johnson’s EO creating Affirmative Action, despite each having clear authority to do so (Hayward, 2025). In some cases, Republican presidents consolidated civil rights state expansions established by their Democratic predecessors (Richard Nixon Foundation, 2017; Donius & Gregg, 2012).

Transforming the Civil Rights State (and Politics)

The election of President Trump in 2024 will be among the most consequential events of the 21st century. Upon taking office on January 20, 2025, President Trump immediately revoked a host of his predecessor’s executive actions, including those that had embedded DEI policies throughout the federal government (The White House, 2025a).[8] The president’s executive actions in the civil rights domain constitute a sweeping reorientation of civil rights enforcement.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

The term “DEI” is commonly used in reference to three distinct categories of racially discriminatory policies and programs. The first and original use of the term pertains to diversity training programs rooted in oppressor/oppressed group themes derived from critical race theory (CRT) and related “neo-Marxist” academic fields (Swain & Schorr, 2021; Swain & Towle, 2023). These programs subject employees to racially hostile environments characterized by racial stereotyping and denunciations, and requirements for certain employees (e.g., whites or men) to confess their supposed personal, collective, or inherited guilt for indignities suffered by members of other groups (Rufo, 2020; Singal, 2021).

The term “DEI” is also sometimes used to refer to “diversity statements,” or written prompts for job applicants to describe their championing of the same neo-Marxist or “woke” premises embedded in DEI training. For example, UC San Diego instructs faculty applicants to do the following:

Describe your understanding of the barriers that exist for historically under-represented groups in higher education and/or your field. This may be evidenced by personal experience and educational background. For purposes of evaluating contributions to diversity, under-represented groups (URGs) include [sic] under-represented ethnic or racial minorities (URM), women, LGBTQ, first-generation college, people with disabilities, and people from underprivileged backgrounds…

Describe how you plan to contribute to diversity at UC San Diego, including activities you would pursue and how they would fit into your research area, department, campus, or national context (UC San Diego, n.d.).

Diversity statements operate as modern “religious tests” for employment insofar as they enable human resources teams to screen out applicants found to lack sufficient commitment to the shifting tenants of the progressive creed (McBrayer, 2022).[9]

Finally, “DEI” is sometimes used as a synonym for affirmative action (Riley, 2025). Of course, such policies predate DEI by decades, yet the conflation of the two terms hints at an important truth. Enforcing ideological conformity in the workplace through DEI “struggle sessions” and “religious tests” serves to reinforce the use of discriminatory racial preferences to mitigate outcome disparities. It is this animating spirit—the unwritten constitution of the modern civil rights state—that unites the three uses of the term “DEI.” In this sense, one could say that DEI was part of the modern civil rights state from its very beginning.

To its credit, the Trump Administration understood the connection between DEI and the modern civil rights state much better than most observers.[10] In addition to revoking President Biden’s DEI EOs, President Trump signed a second EO directing federal agencies to

Terminate, to the maximum extent allowed by law, all DEI, DEIA, and “environmental justice” offices and positions (including but not limited to “Chief Diversity Officer” positions); all “equity action plans,” “equity” actions, initiatives, or programs, “equity-related” grants or contracts; and all DEI or DEIA performance requirements for employees, contractors, or grantees.[11]

The same order requires federal hiring and evaluation to be based on “individual initiative, skills, performance, and hard work” (The White House, 2025b).

On his second day in office, President Trump extended his DEI purge to the private sector, directing federal agencies to terminate enforcement of all “discriminatory and illegal preferences,” including “illegal private-sector DEI preferences, mandates, policies, programs, and activities” (The White House, 2025c).[12] In many respects, this is the most consequential of the three orders. In effect, the president’s order redirects one of the two primary enforcement arms of the modern civil rights state (the other being the courts) towards eliminating that state’s unwritten constitution. To this end, the same EO revokes President Johnson’s EO 11246, thereby eliminating the federal affirmative action mandate for federal contractors (Johnson, 1965).

Three months after taking office, President Trump delivered yet another devastating blow to the unwritten constitution by targeting disparate impact liability. The order revokes previous executive guidance on the subject, and it instructs executive departments and agencies to deprioritize enforcement of associated statutes and to mitigate the use of disparate-impact liability within their jurisdictions. Finally, the order tasks the Attorney General and EEOC Chair to take additional actions to prevent discrimination (The White House, 2025d; Schorr, 2025a).

On the same day, President Trump signed a fourth DEI EO, this time taking aim at racial discrimination in K-12 schools (The White House, 2025e). The president’s order revokes a 2014 Obama Administration guidance document (“Dear Colleague Letter”) that had threatened school districts with civil rights investigation should they fail to reduce school disciplinary outcome disparities between white and black students (U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Education, 2014). The practical effect of the Obama guidance had been to force schools to adopt more lax disciplinary standards for black students. This perverse application of civil rights law had not only inverted Title VII, by all-but mandating disparate treatment, but it also made schools measurably less safe (DeVoss, 2018).

Antisemitism

On his first day in office, President Trump issued the first of two EOs responding to civil rights violations against Jewish students at elite universities. The president’s first antisemitism EO directs federal agencies to improve security vetting for international students, and it directs the Department of Homeland Security to remove any such students found to support US-designated foreign terrorist organizations (The White House, 2025i). The president’s second EO directs federal agencies to prioritize civil rights protections for Jewish students (The White House, 2025j).

These orders followed several disastrous Congressional hearings in which university leaders had appeared oblivious to their civil rights obligations as recipients of federal funds (Pidluzny, 2024). However, much like their toleration of discriminatory DEI policies, universities’ toleration of harassment and intimidation of Jewish students fits within the bounds of the unwritten constitution. Jewish students have civil rights protections on paper, under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act; however, in practice, being designated as “white” or “white adjacent” by the shifting “intersectional” standards of the day rendered such protections nonoperative (Bernstein, 2022; Schorr, 2024).[13] Paradoxically, under the modern civil rights state, individuals categorized as belonging to “privileged” groups are relegated to second-class status.

Gender Ideology

On his first day in office, President Trump took the first of several executive actions addressing civil rights violations rooted in gender ideology. At the time of this writing, President Trump has issued two EOs addressing Title IX protections for women and girls, one EO addressing ideological indoctrination in K-12 schools, and one EO addressing chemical and surgical “gender affirming” mutilations of children (The White House 2025k; 2025l; 2025m; 2025n).

The president’s first gender ideology-related EO begins by recognizing that efforts to redefine the categories of “women” and “girls” to accommodate subjective gender identity claims by men have the effect of denying civil rights protections under law to actual women and girls. The order goes on to restore the historic, biological understanding of sex distinctions in federal law, including in Title IX, and it directs federal agencies to enforce legal protections for intimate single-sex spaces—e.g., bathrooms, locker rooms, and domestic abuse shelters—from opposite-sex intrusion. The order additionally puts states on notice that they will be held accountable for crimes committed by male inmates against female inmates in women’s correctional facilities where men are housed in defiance of federal law (The White House, 2025k).[14]

President Trump’s second gender ideology-related EO addresses radical ideological indoctrination in K-12 schools.[15] The order directs the Attorney General and the Secretaries of Education, Health and Human Services(HHS), and Defense to develop a strategy to end indoctrination rooted in gender ideology and “discriminatory equity ideology” (e.g., CRT), as well as instruction that encourages children to “socially transition” to the gender opposite their sex. Reasoning that such policies likely violate one or more federal laws—including Title VI (CRA, 1964), Title IX (1972), the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and the Protection for Pupils Rights Amendment—the order calls for withdrawing K-12 school federal funding and investigating schools for sexually exploiting minor children, as appropriate (The White House, 2025l).

The president’s third gender ideology EO targets so-called “gender-affirming” medical interventions for minor children: puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and sex-reassignment surgeries. These dangerous and irreversible procedures mutilate the healthy bodies of minor-aged children to support (aka, “affirm”) subjective and unscientific gender identity claims (Schorr, 2025b). The order instructs federal agencies to rescind all policies relying on guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health—a discredited activist group that presents itself as a neutral scientific body—and to end all federal support for such procedures (Hughes, 2024). The Secretaries of Health and Human Services and Defense are further instructed to take all appropriate actions to end these procedures (The White House, 2025m).

The president’s fourth gender ideology EO revisits Title IX. Specifically, it instructs the Departments of Education and Justice to enforce equal access for female athletes, and to prioritize enforcement actions against education institutions violating their civil rights responsibilities as recipients of federal funds (The White House, 2025n).

Race is uniquely central to the modern civil rights state; however, prohibitions against discrimination along other group identity-based lines have been part of this state since its beginning.[16] Sex, sexuality, disability, and, more recently, subjective gender identity have all been grounds of civil rights legislation, litigation, and administrative and judicial action. Yet not all identity categories are comparable. There are often prudent reasons for treating individuals differently—for discrimination, in other words.[17] Examples include:

- Job requirements that preclude hiring individuals with certain disabilities, such as legally blind pilots (Sutton v. United Air Lines, 1999).

- Sex-based segregation in sports—without which athletic opportunities for women are farcical (Gaines & Schorr, 2024).

- Exclusion from military service, particularly with respect to ground combat (Seck, 2015).

Perhaps practical constraints on equal treatment under law help to account for why recent civil rights abuses related to non-race/ethnicity factors seem to manifest differently. For example, the push to include transgender-identifying men in women’s sports does not neatly map onto a sex or even gender-identity application of the unwritten constitution. The argument is not that men (or perhaps, gender-confused men) have been historically disadvantaged in women’s sports and thus need special accommodations—something akin to a “handicap” in golf. Rather, the argument is for equal treatment of men and women in women’s sports. The result of that argument has been the creation of an absurd new disparity in the form of an overrepresentation of male champions in female sports, as measured by the nearly 900 medals lost by female athletes to male athletes as of March 30, 2024 (Downey, 2024).

Likewise, indoctrinating children does not neatly fit into the race/ethnicity model, nor does subjecting children to medical experimentation. Yet these are all civil rights issues insofar as they concern government protections related to accessing public services and, more generally, to equality under law. In short, the tension between equal treatment and equal outcomes is not the sole civil rights consideration, even if it is front and center in the American civil rights state.

Federal Agencies Respond

The president’s dramatic changes to civil rights enforcement guidance were quickly followed by similarly dramatic enforcement actions by executive branch departments. At the time of this writing, the Department of Education has sent warning letters to more than 60 universities notifying them of investigations in response to reported civil rights violations against Jewish students (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2025). These investigations have resulted in the apparent withdrawal of over $7.8 billion in federal grant and contract funding and other penalties, including curtailed access to international students and challenges to university accreditation (see Table 1).

Table 1

Trump Administration Actions Taken in Response to Title VI Civil Rights Violations

| University | Date | Department(s) | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia Univ. | 3/7/2025 | ED, DOJ, HHS, GSA | Cancellation of $400m in grants and contracts; challenge to accreditation [18] |

| Univ. of Pennsylvania | 3/19/2025 | ED, HHS, DOD | Suspension of $175m in grants [19] |

| Princeton Univ. | 4/1/2025 | DOE, DOD, NASA | Suspension of $210m in grants [20] |

| Brown Univ. | 4/3/2025 | ED, DOJ, HHS | Block on $510m in grants [21] |

| Cornell Univ. | 4/8/2025 | DOD | Freeze on $1b in grants [22] |

| Northwestern Univ. | 4/8/2025 | HHS, DOC | Freeze on $790m in grants [23] |

| Duke Univ. | 7/29/2025 | ED, HHS | Freeze on $108m in grants [24] |

| UC, Los Angeles | 7/31/2025 | HHS, NSF | Freeze on $584m in grants [25] |

| Harvard Univ. | 4/14/2025 | ED, DOJ, HHS, GSA | Freeze on $2.2b in grants and $60m in contracts; $450m grant funding reduced; pause on international students; challenge to accreditation [26] |

| Grant Receiving Universities | 4/11/2025 | DOE | Reduced support for annual indirect research costs: $405m [27] |

| Grant Receiving Universities | 5/14/2025 | DOD | Reduced support for annual indirect research costs: $900m [28] |

The most significant penalties to date have been imposed on Columbia University and Harvard University. In both ongoing cases, the Department of Education has connected Title VI violations against Jewish students to extract a broader set of civil rights reforms, including those pertaining to:

- Governance and leadership

- Merit-based hiring and admissions

- DEI offices and policies

- Student discipline and campus safety

- Antisemitic academic programs

- Whistleblower protections

- Transparency and compliance (Armstrong, 2025; Gruenbaum et al., 2025).

The Trump Administration’s strategy involves leveraging settlement or “voluntary compliance” agreements. Settlement agreements are formal, legally binding commitments by a regulated entity (e.g., a university) to undertake specified remedial actions. A settlement agreement can resolve an enforcement agency’s investigations into alleged unlawful practices while sparing both parties the time and cost burdens of prosecution.[29] The contractual nature of settlement agreements enables the government to extract broader concessions than those mandated by law, as prior administrations have demonstrated.[30]

The Trump Administration’s letter to Harvard University illustrates the merits of this approach. In its civil rights enforcement capacity, the Trump Administration is investigating Harvard in response to well-documented instances of the university failing to protect Jewish students from harassment and intimidation. However, the campus antisemitism crisis did not occur in a vacuum. At Harvard, as on other elite campuses, antisemitism, widespread violations of speech rights, and the overall climate of political intolerance result from a near-total absence of viewpoint diversity (Schorr, 2025d). Campus “monocultures” of this sort are not organic; they are the intentional result of relentless viewpoint discrimination against non-leftist faculty, students, and visitors (Schorr, 2025e).

Viewpoint discrimination is well-documented, and its impacts are measurable. For example, a 2021 survey found that one in five U.S. academics (20%) would discriminate against a conservative grant applicant, and four in 10 (40%) would oppose hiring a Trump supporter (Kaufmann, 2021). This means that an openly conservative faculty member undergoing review by randomly selected peers would face an 80% likelihood of being discriminated against for his or her political views. Similarly, a survey of social and personality psychologists uncovered widespread support for discrimination against conservative colleagues in cases of:

- Reviewing academic work or inviting colleagues to present their work (one in six).

- Reviewing grant applications (one in four).

- Hiring decisions (one in three) (Inbar & Lammers, 2012).

Viewpoint discrimination fosters hostile campus intellectual and social climates. Faculty surveys indicate that university campuses are more hostile to dissenting ideas today than they were during the McCarthy Era (Honeycutt, 2024). Unsurprisingly, the brunt of this hostility falls on conservative-leaning faculty, students, and visitors. For example:

- Among faculty, conservatives are more likely than liberals to report fearing reputation costs from their colleges (52% vs. 35%), including losing their jobs (32% vs. 18%; Honeycutt, 2024).

- Among students, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to report self-censoring (49% vs. 38%) and are less likely to report feeling that their free speech rights are secure (34% vs. 51%; Knight Foundation & Ipsos, 2024).

- Among visitors, successful disruptions of campus speakers occurred 10 times more often from the Left (213) than from the Right (23), from 1997-2024 (Schorr, 2025e).

At the same time, institutionalized viewpoint discrimination doesn’t only harm conservatives. A recent survey of four-year college faculty found widespread fear of suffering reputation costs (40%), or of being fired (23%), in retaliation for one’s academic work or public views. A third of faculty (35%) admit to “toning down” their writing. A quarter (27%) admit to being afraid to speak openly (Honeycutt, 2024).[31] Given widespread viewpoint discrimination in faculty hiring, estimates of this size necessarily include many non-conservatives. There simply are not enough conservative faculty to account for estimates in this range (Abrams & Kalid, 2020).

Similarly, among students, the proportion who rate their free speech rights as “secure” recently nosedived, dropping 30 points from 2016 to 2024. In 2024, two in three students reported self-censoring. Tragically, the same proportion (two-thirds) recognized that self-censorship undermines the value of their education (Knight Foundation & Ipsos, 2024).

Viewpoint discrimination robs faculty and students of opportunities for thoughtful engagement with alternative viewpoints. The resulting absence of viewpoint diversity, in turn, causes campus climates to degenerate into ideological echo-chambers and hotbeds of radicalization.[32] Viewpoint discrimination is not prohibited under civil rights law; however, Title VI settlement agreements provide opportunities to strike at the root of what ails modern universities—something the Trump Administration seems intent on doing (Gruenbaum et al., 2025; Schorr, 2025d).

Policy Change Momentum Builds

At the time of this writing, the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement actions are bearing fruit. In March of 2025, shortly after the Administration withdrew $400 million in federal grants and contracts from Columbia University and threatened its accreditation, the university agreed to substantial concessions, including:

- Adopting the International Holocaust Remembrance Association (IHRA) comprehensive working definition of antisemitism.

- Breaking ties with “Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions” organizations responsible for the 2024 university encampments.

- Implementing antisemitism education programs for students, faculty, and staff.

- Implementing security improvements and stricter disciplinary standards for disorderly conduct, violence, and harassment.

- Increasing investigations of civil rights abuse claims.

- Adopting a policy of institutional political neutrality.

- Hiring new faculty and issuing new research grants with an aim to improve campus intellectual diversity (U.S. Department of Education, 2025a, 2025b; Armstrong, 2025; Shipman 2025).

A subsequent settlement agreement with the Trump Administration, signed in July of 2025, restored Columbia’s access to $400 million in research funding in exchange for adopting an even broader suit of reforms and paying a total of $221 million in penalties. Per its settlement, Columbia agrees to:

- Pay $200 million to the U.S. Treasury and an additional $21 million to the EEOC fund to compensate Jewish victims of campus antisemitism.

- Ongoing federal resolution monitoring to verify compliance.

- Abandon racial preferences in student admissions, including preferences utilizing applicants’ personal statements (supported by data reporting to the resolution monitor).

- Adopt merit-based faculty hiring without regard to race or other identity considerations (supported by data reporting to the resolution monitor).

- Provide the government with additional oversight of foreign students and to cooperate with federal government information requests.

- Train students emphasizing American norms and values, including “civil discourse, free inquiry, open debate, and the fundamental values of equality and respect.”

- Comply with legally mandated foreign gift and contract reporting requirements and take additional such actions as needed to address funding from criminal and terrorist organizations and adversary nations.

- Reduce foreign student enrollment.

- House students by sex, rather than “gender identity,” upon student request.

- Segregate athletic programs and intimate facilities by sex (Columbia University, 2025; The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2025; Reuters, 2025).

Taken together, these concessions represent an enormous overhaul. The standardization of policy changes like these across the higher education landscape would be nothing short of transformative. To be sure, the Columbia settlement is the largest to date; however, the Administration has also extracted significant policy concessions in settlement agreements with Brown University and the University of Pennsylvania (Penn). These include commitments related to merit-based admission, hiring, and promotion (Brown), and terminating transgender inclusion in sports and intimate facilities (Brown and Penn) (The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2025).[33]

In contrast to Columbia, Brown, and Penn, Harvard has resisted the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement efforts, opting to sue the Administration rather than comply with, or even negotiate, the terms of its proposed settlement (Powell, 2025). At the same time, Harvard, like Columbia before it, has preemptively conceded to many of the Administration’s concerns. For instance, Harvard has agreed to:

- Adopt the IHRA antisemitism definition.

- Alter its civil rights complaint reporting system.

- Implement antisemitism training for “the university community” (presumably students, and possibly faculty and staff)

- Upgrade security and address school discipline procedures.

- Remove the faculty heads of Harvard’s Center for Middle East Studies, a program associated with antisemitism complaints (Harvard University, 2025a; Mao & Paulus, 2025).

Additionally, several Harvard graduate schools have also shuttered their DEI offices, and the university has even signaled a willingness to address its lack of viewpoint diversity (Church & Srivastava, 2025; Harvard University, 2025b; Belkin et al., 2025).

Harvard’s “hardball” approach does not appear to be working. The Trump Administration continues to escalate pressure on the university through additional funding freezes, a ban on international students, threats to revoke the institution’s nonprofit status, and, recently, a challenge to its accreditation (U.S. Department of Education, 2025c; The White House 2025o; Cochran, 2025; U.S. Department of Education, 2025e).[34] The problem Harvard faces—and that other universities are likely to face—is the tremendous scope of authorities that the civil rights state places in the hands of the executive branch. Legal challenges can stall and blunt these authorities, but the Administration clearly holds the high ground.

National sports associations have also heeded the Administration’s focus on protecting women and girls. The day after the president banned male athletes from female sports via executive order, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) reversed course by banning male athletes from competing in female sports (NCAA, 2025). Shortly after, the University of Pennsylvania did the same and corrected its records to reflect victories and trophies won by women in women’s sporting events (U.S. Department of Education, 2025f). Several states are resisting the president’s order (Whittle, 2025; Karnowski, 2025); however, the shift in national policy and momentum is undeniable.

Many regulated institutions are voluntarily complying with the terms of the new civil rights state. For example, the University of Michigan terminated its vaunted DEI regime in March of 2025 (Bianco, 2025).[35] Additional university DEI office closures have been announced by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Purdue, Ohio State, and Case Western Reserve, among others (Kornbluth, 2025; Wolfe, 2025; Hancock, 2025; Tamburo, 2025).[36] Many states are complying with the Administration’s DEI ban in K-12 schools even as the Department of Education’s requirement for schools to affirm their compliance in writing works through legal challenges (Binkley et al., 2025; U.S. Department of Education, 2025g). Similarly, major corporations have announced sweeping changes, including abandoning racial and ethnic hiring targets, terminating diversity training programs and projects, severing ties with DEI proponents, and deleting webpages that had boasted of how companies were supporting miscellaneous race, sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity causes (Schneid, 2025).

Where the business community is concerned, it is likely that these voluntary efforts are the beginning of a larger trend. To date, the Trump Administration’s civil rights focus has primarily centered on Title VI enforcement in higher education. As those efforts wrap up, the Administration will be able to devote greater attention to Title VII enforcement in the private sector. It will do so having already:

- Defined DEI employment practices as illegal discrimination (The White House, 2025c).

- Withdrawn authorization for racial discrimination under the guise of federal affirmative policies and explicitly prohibited those policies (The White House, 2025c).

- Prohibited disparate impact discrimination in employment (The White House, 2025d).

These tools will provide important sources of leverage for the Administration’s efforts to ensure equality under law for all American citizens. The Administration can additionally count on broad support from the Supreme Court and the American people.

Legal and “Vibe” Shifts

Broad political change rarely occurs in a vacuum. The modern civil rights state was formed through transformative legislation, executive actions, and court rulings; however, these actions occurred alongside (sometimes leading and sometimes following) major changes in public opinion. The new civil rights state is distinct from its predecessor in that it draws on preexisting (albeit selectively enforced) legislative foundations, leaving executive action to drive major policy change. However, like its predecessor, the new civil rights state finds support in changes in both judicial precedent and public opinion.

Beginning with the courts, much as the Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968) and key legislation victories followed in the wake of the Supreme Court’s pivotal Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the new civil rights state follows in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in Students for Fair Admission (SFFA) v. Harvard in 2023. In the latter case, the Supreme Court ruled that racially “conscious” (i.e., discriminatory) college admissions violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act (1964).[37] As noted, a plain reading of these documents provides the best defense for the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement strategy. In providing such a read, the Supreme Court laid the legal predicate for the Trump Administration’s campaign against DEI.[38]

In another recent landmark case, Ames v. Ohio Department of Youth Services (2025), the Supreme Court ruled that members of so-called “majority groups” (e.g., white people, men, and heterosexuals) cannot be held to a higher evidentiary standard in Title VII employment discrimination cases. The decision was a clear repudiation of the modern civil rights state’s unwritten constitution and an unmistakable victory for equality under law. Remarkably, the Court’s decision was unanimous. This may signal that the Court’s liberal wing may be resigning itself to the end of the unwritten constitution.

The Supreme Court’s decision in yet another landmark case, United States v. Skrmetti (2023), establishes the legality of state bans on transgender medical procedures for minor children. The Court will next address Title XI questions related to male participation in female sports later in 2025 (Howe, 2025). As noted, the unwritten constitution does not always neatly fit onto non-race/ethnicity issues in the modern state; yet a systemic bias in favor of members of allegedly “oppressed” or “marginalized” groups has been a consistent theme of that state, logical inconsistencies aside. Skrmetti (2023) once again defies this bias, bolstering the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement agenda.

Civil rights state transformation is similarly evident in recent shifts in public opinion. For example, consider the following developments organized by issue area:

- DEI – After a period of rapid ascendance during which public criticism could easily end one’s career, the public is now sharply divided on the topic of DEI (Bowman, 2025). As noted, the term itself sometimes refers to training programs, hiring statements, and affirmative action policies. The last of these is now highly unpopular. For example, a recent survey of public attitudes towards affirmative action found an average of seven in 10 (roughly 70%) respondents oppose race-based admissions in higher education (Hartney & Mukherjee, 2024).

- Racial grievance protests – In sharp contrast to the George Floyd/Black Lives Matter Riots of 2020, the recent Los Angeles riots against immigration enforcement failed to generate widespread sympathy from the American public (Lubin, 2025). Corporate America likewise appears to be sitting this one out (Hawkins, 2025).

- Transgender rights – The term “transgender rights” is a euphemism for policies that aim to embed gender ideology in American society. These policies, and the premises that inform them, are deeply unpopular. For example, 79% of Americans oppose policies allowing men to compete in women’s sports (Miller, 2025), 68% oppose providing children access to puberty blockers (Gans, 2023), 76% opposing teaching children they can change their gender (Rasmussen, 2023a), and 60% oppose allowing men in women’s locker rooms, showers, and bathrooms (Rasmussen, 2023b). Interestingly, teenagers are even more likely (69%) than all Americans (65%) to agree that gender is determined by sex at birth (Horowitz, 2025). At the time of this writing, most states have enacted laws protecting children from chemical and surgical mutilation (Schorr, 2025f). This reversal of acceptance of gains by members of a supposedly marginalized group is perhaps the first of its kind, following the Civil Rights Movement. Opposition to transgenderism also seems to be driving reduced support for other LGBT issues, like same-sex marriage (Duggan, 2024).

- Political correctness – Public figures, including politicians and business leaders, seem less restricted by the speech norms associated with the prior civil rights state where “marginalized groups” are concerned (Clarence-Smith, 2025). Evidence from survey experiments suggests the wider public has grown less sensitive to these concerns as well (Valentino et al., 2018).

Following President Trump’s election in 2024, the term “vibe shift” was widely employed to describe a widely felt sense that the country had turned a cultural corner, rendering formerly taboo beliefs acceptable (Kelly, 2024). The term could also have been applied to an earlier set of mass public attitude changes—those that accompanied the emergence of the modern civil rights state. The spirit of toleration towards de facto legal inequality for members of so-called “majority groups” as a means of remedying past injustices was certainly a kind of vibe. While it may be too early to tell whether recent shifts in mass public sentiment will be comparably impactful, the coincidence of this movement with dramatic policy shifts suggests the country is charting a new course.

A New Civil Rights State

What are likely to be the contours and qualities of the new civil rights state? At the time of this writing, ten months into the new administration, much remains in flux. At the same time, the extraordinary pace of the Trump Administration’s enforcement efforts provides some early answers to this question.

First, through the Department of Justice, the EEOC, and other executive branch agencies, the new civil rights state will institutionalize a new set of interpretative norms and assumptions to guide the application of civil rights law. This new unwritten constitution will emphasize equal treatment and meritocracy. It will reject group-based claims of special privilege and group-specific assumptions when evaluating discrimination cases and controversies. It will reject equal outcomes as a standard of evaluation and as an endpoint for civil rights enforcement. As such, it will regard policies intended to produce equal outcomes with suspicion, understanding that they almost invariably require illegal discriminatory treatment to achieve their intended goals.

In contrast to the prior civil rights state, this implicit set of interpretative norms and assumptions will derive from (rather than be in tension with) the nation’s primary civil rights texts. One might then ask how these norms and assumptions constitute an unwritten constitution?

The president’s April 23, 2025, executive order on disparate impact discrimination helps to demonstrate the continued utility of this framing. As noted, the 1991 Civil Rights Act is something of a rarity in American law in that it provides a statutory basis for denying individuals equal treatment under the law. The president cannot unilaterally revoke this law. However, within the scope of his executive discretion, he can “eliminate the use of disparate-impact liability in all contexts to the maximum degree possible to avoid violating the Constitution, federal civil rights laws, and basic American ideals” (The White House, 2025d; italics added).

Figure 1

American Civil Rights States: 1789 through the Present [39]

Second, as this new set of civil rights enforcement norms takes root, elected officials will have opportunities to amend or repeal laws passed during the prior civil rights era that established or encouraged discriminatory treatment. The Department of Justice, state, and private litigants may also seek to overturn Supreme Court rulings that provided a basis for these policies, such as the Griggs v. Duke Power Company (1971) decision.[40]

Third, the scope of the new civil rights state will be more limited than that of its immediate predecessor, though more expansive than that of the early civil rights state. The new civil rights state will be smaller, cheaper, and less intrusive because its aims (equal treatment) are far less sweeping. Transforming the whole of society to eliminate prejudice everywhere in American life was an absurdly large, unworkably, and quasi-totalitarian endeavor. Defenders of the modern civil rights state will correctly note that institutionalized racial discrimination was an appalling stain on the soul of a nation rooted in freedom and equality under law. However, Jim Crow was buried six decades ago and recent woke excesses have rendered the costs of institutionalized discrimination in pursuit of equitable outcomes increasingly intolerable.

Fourth, the new civil rights state will target instances of discrimination ignored by the prior civil rights state. It will draw on existing—and, in some cases, new—civil rights authorities to construct a limited and transparent civil rights enforcement apparatus to cover all Americans equally. This task must also address gaps left by the prior civil rights state, as doing otherwise would violate the principle of equality under law. Targets will include discrimination against members of formerly disfavored groups (e.g., whites, Asians, and Jews) in college admission, scholarships, employment, business loans, and the like. Similarly, formerly tolerated discrimination against Christians and Jews will need to be addressed. The new civil rights state will also need to address viewpoint discrimination in higher education, including in hiring, promotion, admissions, speech codes, and in discriminatory policies governing speaking events.

A Call for Research

The pace and scope of the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement changes took most observers by surprise; however, the research grounds were laid by several leading figures. These include journalist Christopher Rufo and two academics: Christopher Caldwell and Richard Hananiah. The think tank community has contributed ample research addressing many of the surrounding issues; however, this issue area requires further development. Such research would help to support efforts of key Trump Administration civil rights reformers, including Harmeet Dhillon, the U.S. Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division.

Policy makers and the public would benefit from additional research to develop best practices for implementing the new civil rights reforms. For example, many universities and some businesses are likely to continue to resist compliance due to strong ideological commitments to what the Administration has termed “discriminatory equity ideology” (The White House, 2025l). Current strategies include rebranding DEI offices and shuffling DEI staff to other departments and utilizing “personal statements” to award illegal race-based preferences to applicants from favored groups (Schorr, 2025f; Knox, 2025).[41]

Additionally, the Trump Administration’s commitment to abolishing the Department of Education adds a layer of complexity to civil rights enforcement. Presumably, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) will be housed alongside the Department of Justice’s OCR. The two may even be merged. The impact of this move on civil rights enforcement is unclear. Streamlining enforcement could be beneficial in terms of efficiency and consistency; however, the cultures of two departments have historically differed, with the Department of Education issuing broad guidance (e.g., “Dear Colleague” letters) to help schools come into compliance with federal civil rights law rather than targeting and punishing noncompliance. Further research addressing optimal organization and enforcement strategies may be needed.

Repealing the 1991 Civil Rights Act and overturning Griggs will also require careful planning. State-level policy experimentation may create opportunities for limiting the reach of these modern civil rights state holdovers, and for setting up legal challenges to them. The states-as-laboratories approach may also be useful in other ways.

Finally, the political impact of the civil rights state transformation merits investigation. How will party coalitions change as the Democratic Party’s defining paradigm unwinds? Politics are dynamic. A coalition constructed along certain lines will naturally include and exclude certain policies. The Democratic Party’s commitment to a Civil Rights Movement Era framing currently prevents it from addressing pressing public safety and quality of life issues—perhaps, most especially for its own voters—and commits it to championing ever more bizarre niche sexual and “identity” causes. The America First movement could benefit from a more developed understanding how reshaping the legal foundations for this politics could interact with party coalitions to shift the “Overton window” on a range of policy issues.

APPENDIX A:

Trump Administration Executive Orders Addressing Civil Rights Enforcement

| Executive Order | Date | Department(s) | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Recission of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions | 1/20/2025 | All agencies | Rescinds 78 Biden Administration executive orders |

| Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing | 1/20/2025 | DOJ | Terminates federal government DEI programs |

| Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity | 1/21/2025 | DOJ, ED | Prohibits illegal identity-based preferences in the private sector |

| Protecting the United States from Foreign Terrorists and other National Security and Public Safety Threats | 1/20/2025 | DOS, DOJ, DHS, DNI | Suspends or limits visas for nationals from countries with deficient screening and high security risks |

| Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government | 1/20/2025 | HHS, DOS, DHS, DOJ, HUD, DOL | Recognizes immutable biological sex for federal policy purposes |

| Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation | 1/28/2025 | HHS, DOJ, DOD | Bans gender transition treatments for minor children |

| Additional Measures to Combat Antisemitism | 1/29/2025 | DOJ, ED, DOS, DHS | Mobilizes agencies to actively combat campus and public antisemitism |

| Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling | 1/29/2025 | ED, DOD, HHS, DOJ | Cuts federal funding for radical ideology in K-12 schools |

| Keeping Men out of Women’s Sports | 2/5/2025 | ED, DOJ, DOS, DHS | Rescinds federal funds and bars male participation in female sports |

| Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy | 4/23/2025 | DOJ, HUD, FTC | Eliminates executive support for disparate-impact liability |

| Reinstating Common Sense School Discipline Policies | 4/23/2025 | ED, DOJ, DOD, HHS, DHS | Restores support for objective, behavior-based school discipline policies |

FOOTNOTES

[1] Civil liberties describe protections from government. They include such things as the freedom of speech and religion, privacy rights, and due process (Cornell Law School, n.d.-a). Civil rights describe rights provided by government related to equality under law. They include such things as equal protection under law, voting rights, and protections against discrimination (Cornell Law School, n.d.-b).

[2] Race/color discrimination is prohibited by the Civil Rights Act (1964) in public accommodations (Title II), employment (Title VII), and in programs receiving federal funds, including schools (Title VI); by the Fair Housing Act (1968) and Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974) in housing; and by the Voting Rights Act (1965) in voting. National Origin discrimination is prohibited in programs receiving federal funds, (Civil Rights Act, 1964, Title VI) and in employment (Civil Rights Act, 1964, Title VII; Immigration and Nationality Act, 1952). Sex discrimination is prohibited by the Civil Rights Act (1964, Title VII) and by the Equal Pay Act (1963) in employment, by Title IX of the Education Amendments (1972) in education, by the Fair Housing Act (1968) in housing, and by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010, Section 1557) in health care. Religious discrimination is prohibited by the Civil Rights Act (1964, Title VII) in employment, by the Fair housing Act (1968) in housing, by the Equal Access Act (1984) in education, and broadly under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993). Disability discrimination in is prohibited by the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) in any program receiving federal funds, by the Rehabilitation Act (1973) in public entities, including public schools and public housing; and by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (1990) in education. Age discrimination is prohibited by the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (1967) in employment and by the Housing for Older Persons Act (1995) in housing. Genetic information discrimination is prohibited by the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (2008) in employment. “Familial status” discrimination (e.g., discrimination against families with children) is prohibited in housing by the Fair Housing Act (1968). Additionally, the 24th Amendment protecting voting rights by banning poll taxes, which disproportionately impacted poor Americans (U.S. Const. amend. XXIV, 1964).

[3] In The Age of Entitlement (2020), Christopher Caldwell describes the modern civil rights state as a new constitution.

[4] In line with this understanding, the D.C. district court incredulously dismissed a racial discrimination claim filed by a white plaintiff in Parker v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (1981). While conceding that “Whites are also a protected group under Title VII,” the court stated, “it defies common sense to suggest that the promotion of a Black employee justifies an inference of prejudice against white co-workers in our present society.”

[5] See for example, Trende (2012), and Heersink & Jenkins (2020).

[6] SPLC “extremists” include Focus on the Family, Moms for Liberty, the American College of Pediatricians, the Center for Immigration Studies, Alliance Defending Freedom, Federation for American Immigration Reform, the Family Research Council, Prager University, and Charles Murray.

[7] Survey questions generally ask respondents their own feelings on specific civil rights related questions. They rarely ask respondents about civil rights per se, or to rate the parties on civil rights. However, the American National Elections Studies (ANES) asked a subset of respondents “which party is better for Blacks?” in 2002. Respondents rated Republicans (4.45%) well behind Democrats (35.8%) and “Not much difference between them (57.79%) (ANES, 2002).

[8] See Appendix A for a table of recent Trump Administration executive orders addressing civil rights enforcement.

[9] A recent lawsuit filed by the America First Policy Institute against Cornell University includes evidence of diversity statements being weaponized to impose a “DEI orthodoxy” in the workplace (Steinmann & O’Neill, 2025).

[10] Conservative and liberal critics of woke excesses (e.g., CRT, DEI, and gender ideology) have emphasized the impact on the marketplace of ideas of the “long march through the institutions” by progressives (Lindsay, 2021; Rufo, 2022). Hanania (2023) argues this discourse neglects the more important role played by civil rights law. The point matters because a strategy predicated on the latter view would tend towards immediate action using civil rights enforcement authorities rather than a generational replacement strategy.

[11] In a separate same-day EO, President Trump signed detailed instructions for a merit-based (DEI-free) federal hiring plan (The White House, 2025f).

[12] President Trump signed separate EOs abolishing DEI preferences and programs in the Departments of Defense and State (The White House, 2025g; The White House, 2025h).

[13] Intersectionality is a core CRT concept that emphasizes the importance of overlapping dimensions of social oppression (e.g., race, sex, sexual orientation, and class) (Crenshaw, 1989). When combined with a “sacred victims” orientation towards members of so-called “marginalized” groups, intersectionality forms the basis for competitive rights claims and status-seeking rooted in comparative levels oppression (Kaufmann, 2024). Despite having historically suffered discrimination, Jews occupy a low position on the intersectional totem pole—below non-white minorities but above non-Jewish whites. Consequently, in the modern progressive or “woke” paradigm, Jews lack adequate moral standing to assert civil rights claims against discrimination or abuse from (or on behalf of) more oppressed groups, such as Palestinians or Muslims (Berstein, 2022).

[14] Placing male inmates in female correctional facilities has resulted in instances of rape and pregnancy occurring inside (ostensibly) women-only facilities (Reilly, 2022; Downing, 2024).

[15] The EO in question also addresses race (e.g., CRT) alongside gender ideology indoctrination and the promotion of social transitioning—another “gender ideology”-linked civil rights concern (The White House, 2025l).

[16] Title VII prohibitions against sex discrimination were added to CRA (1964) as a “poison pill” amendment from a segregationist Democrat Senator in a bid to reduce support for the bill (Gold, 1980).

[17] Recognizing the legitimacy of gender discrimination, in some cases, courts evaluate gender discrimination claims under an “intermediate” rather than a “strict” scrutiny test (Cornell Law School, n.d.-c).

[18] See: U.S. Department of Justice Office for Public Affairs (2025); U.S. Department of Education (2025d).

[20] See: Princeton University (2025).

[21] See: Brown University (2025).

[22] See: Crouson, Jaryn. (2025).

[23] See: Crouson, Jaryn. (2025).

[24] See: Creitz, Charles. (2025).

[25] See: University of California, Los Angeles (2025); Watson (2025).

[26] See: U.S. Department of Education (2025c, 2025d, 2025e); The White House (2025o).

[27] See: U.S. Department of Energy (2025).

[28] See: U.S. Secretary of Defense (2025).

[29] For a more complete description, see the Department of Education Office for Civil Rights’ 2005 Investigations Manual (U.S. Department of Education, 2005).

[30] For example, a Title IV and VI investigation of the University of California (UC) by the Departments of Justice and Education in response to a racially themed fraternity party (“The Compton Cookout”) resulted in a settlement agreement in which UC committed to, among other things: Ongoing federal review and monitoring, a new Office for the Prevention of Discrimination and Harassment, an Office for Diversity Initiatives, a Council on Climate, Equity, and Inclusions; anti-discrimination training for students, faculty and staff; a mural celebrating Mexican heritage (the motivating incident did not involve Latinos); a bias incident reporting system; targeted annual funding ($330k) to recruit racial minority students; commitments to hire minority faculty members; locations reserved for use by racial minority students; a DEI instruction graduation requirement for students; funding for DEI themed conferences and postdoctoral fellowships; and increased staffing for African American and Chicano-Latino Studies departments (again, the incident did not involve Latinos, see Attachment A, UCSD, 2012).

[31] Only 9% of faculty admitted to toning down their writing during the McCarthy Era (Honeycutt, 2024).

[32] Sunstein (2001) discusses online ideological echo-chambers, emphasizing how self-selection into closed information environments reinforces and radicalizes beliefs. This same dynamic would presumably work in person if a system of institutional viewpoint discrimination similarly excludes dissenting perspectives from consideration.

[33] In July, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) agreed to compensate victims of antisemitic harassment. The university is expected to agree to larger settlement agreement with the Trump Administration soon (Norman, 2025).

[34] A district court judge has temporarily blocked the Trump Administration’s effort to prevent international students from attending Harvard University (Quilantan & Gerstein, 2025).

[35] The University of Michigan’s DEI program was a national model before it was recognized as a spectacular failure by no less than the New York Times (Confessore, 2025).

[36] Laws and/or university policies prohibiting or restricting DEI office and programs have also been implemented in Texas, Florida, Kentucky, Nebraska, Alabama, Oklahoma, North Carolina, Utah, Wyoming, Iowa, Kansas, Idaho, and Ohio (Spitalniak, 2024; Bushard, 2024; Hancock, 2025).

[37] The public/private distinction matters where Harvard University and the University of North Carolina (UNC) are concerned. As a private university, Harvard is not bound by the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment but rather by Title VI of the CRA (1964). The UNC is a public university and thus subject to the 14th Amendment.

[38] President Trump and Trump Administration officials have referenced SFFA v. Harvard (2023) in their civil rights enforcement efforts (e.g., The White House, 2025c; 2025p; U.S. Department of Education, 2025g).

[39] Civil rights state dates are approximate and linked to pivotal events, including the ratification of the US Constitution, the end of the Civil War, the passage of the 1964 CRA, and the inauguration of President Trump.

[40] Christopher Rufo addresses this topic, and much of what would come to be the Trump Administration’s civil rights enforcement agenda in a 2024 piece title “A New Civil Rights Agenda” (Rufo, 2024). Current litigation related to “majority-minority” district mandates under the Voting Rights Act can also be viewed through the lens of equity/outcomes-based racial discrimination (National Review, 2025).

[41] Or should we view such rebranding efforts as positive steps towards liberating captured ideologically captured institutions (Fortgang, 2025)?

Works Cited