China-Dominated U.S. Agricultural Sectors Are a National Security Threat

Key Takeaways

• Chinese-owned agricultural companies now hold significant stakes in multiple sectors of the $1.5 trillion American agricultural industry. By definition, these companies are subject to the National Intelligence Law of 2017, which obligates full compliance with state security and intelligence agencies, and the Data Security Law of 2020, which mandates that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) share data with Chinese intelligence services.

• Smithfield, owned by the Chinese WH Group, controls one quarter of U.S. pork processing. This grants them market dominance, enabling them to set prices and establish industry standards.

• Syngenta, owned by a CCP-controlled company ChemChina, lobbies key federal agencies and allegedly engages in systematic IP theft, data scraping, and Uyghur slave labor.

• These and other CCP-affiliated companies pose a serious and ongoing threat to U.S. national security, food supply chains, and economic prosperity.

Introduction

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is dedicated to the systematic exploitation of any opportunities it can detect to degrade the United States’ civilizational architecture, including undermining food supply chains, sponsoring agri-terrorism, engaging in intellectual property theft, appropriating proprietary corporate data, manipulating trading relationships, seizing control of agricultural land and other strategic American real estate, manipulating our political structures, and damaging our general economic health.

Chinese-owned agricultural companies now hold significant stakes in multiple sectors of the American agricultural industry—which constitutes a comprehensive national security threat that must be identified, mitigated, and eventually nullified. American agriculture is a $1.5 trillion industry, accounting for over 5% of the United States' GDP (Zahniser, 2024) and supporting approximately 10% of all American employment (Kassel, 2023). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has acquired key corporations in this space, giving the country control of strategic industry chokepoints. These companies are by definition subject to China’s National Intelligence Law of 2017, which obligates full compliance with state security and intelligence agencies, and to the Data Security Law of 2020, which mandates that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) share data with Chinese intelligence services (U.S. DHS, 2020; Rafaelof et al., 2020). For example, Smithfield, owned by the PRC-based WH Group, controls one-quarter of U.S. pork production (Gelsi, 2025). This has granted them market dominance, enabling them to set prices and establish industry standards (In Re Pork Antitrust Litigation, 2025). Another agri-business, Syngenta, is a state-owned PRC company that lobbies certain key federal agencies that determine U.S. trade and agricultural policy, and it allegedly engages in systematic IP theft, data scraping, and Uyghur slave labor.

Unfortunately, American agriculture currently depends on massive imports of essential equipment, raw materials, and chemicals from overseas. Vital imports include crop protection products, such as herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides, which help maintain healthy and vigorous crop yields while supporting our nation's food security. America cannot afford to leave this fragile system vulnerable to manipulation by foreign adversaries. In fact, one Census line-item alone, narrowly defined as “3808 Insecticides, Rodenticides; Fungicides Etc, Retail,” constituted over $1.2 billion in imports in 2024, with over $200 million of this line-item from China (Census Bureau, 2025).

Success also depends on seed and biotech “trait technologies” and other innovations that increase the productivity of our crops. Innovation free from the persistent threat of IP theft is crucial for crop protection and seed optimization, thus enabling improvements in yields, mitigating natural resistance, and preventing environmental damage. In addition, foreign adversary dominance of key protein supply chains, such as domestic pork production, leaves basic sources of Americans’ caloric intake vulnerable to potential denial and weaponization in the event of a war or international crisis.

A successful America First national security policy necessitates a robust confrontation of this threat. Policy solutions include: 1) a comprehensive review of Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) past approvals for purchases made by Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), 2) legal penalties for unlawful behavior by Chinese SOEs, 3) the expansion of Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) registration requirements for foreign adversary SOEs, 4) a reevaluation of critical agricultural supply chains, and 5) complete implementation of the USDA’s National Farm Security Action Plan.

Smithfield Foods’ Purchase by WH Group: A State-Backed Acquisition Marked by Manipulation and Scandal

The Chinese ownership of Smithfield Foods, a formerly American-owned pork company with a presence in numerous states, raises significant concerns about food security and national security, and is a key example of PRC's growing threat to America's agricultural industry. Smithfield was acquired by WH Group, a Chinese holding company, in 2013 (Reuters, 2013). This was, at the time, the largest-ever acquisition of an American company by a Chinese firm, backed by allocations of preferred loans from state-run and state-affiliated PRC banks (Woodall, 2017, p. 4). The purchase was informed by goals articulated in China’s 12th Five-Year Plan, which instructed food companies to “consolidate and industrialize operations” and also instructed firms generally to “go abroad” in their investments (Slane, 2013). The deal proceeded smoothly under the Obama Administration, despite noteworthy congressional objections from members of both the Democratic (Stabenow, 2013) and Republican parties (Grassley, 2013).

This acquisition is troubling for various reasons. First, Smithfield’s massive market share enables it to effectively set industry standards to its advantage, as it is estimated to be responsible for approximately one-quarter (23%) of the United States' pork processing (Gelsi, 2025). Approximately half of this production originates from farms that Smithfield owns or operates directly, while the other half is sourced from approximately 2,300 contracted farms (Securities and Exchange Commission, 2025). An instructive example is their manipulation of the industry’s use of ractopamine. Ractopamine is a controversial hog growth accelerant and, while China banned the use of ractopamine in 2011, it was still in general use in the United States at that time. Only days before WH Group’s 2013 public announcement of its intention to purchase Smithfield, Smithfield increased the proportion of hogs that did not receive ractopamine from 10% to 50%, a clear response to China’s particular market signals. While nutrition outcomes may have been positive, this demonstrates China’s ability and willingness to manipulate markets in a manner contrary to the preferences of American consumers. Additionally, China has leveraged its market dominance—by way of its ownership of Smithfield—and ability to influence the global COVID-19 response to assert that the U.S. meat industry was “perilously close to the edge” of being unable to supply the U.S. market in the early months of the pandemic (Corkery & Yaffe-Bellany, 2020). Meanwhile, amid these national shortages, Smithfield exported over 9,000 tons of pork to China per month in 2020 (Corkery & Yaffe-Bellany, 2020).

Second, Smithfield’s behavior demonstrates a clear preference for channeling profits back to China, robbing the U.S. market of capital and the U.S. government of tax revenue. Smithfield, while presenting itself as a U.S. company and having filed for listing on the NASDAQ, is still majority-owned by WH Group. As of May 15, 2025, WH Group was reported to hold 92.7% of Smithfield’s common stock (Securities and Exchange Commission, 2025).

Third, Smithfield has been involved in multiple scandals relating to its operations since its acquisition by WH Group in 2013. In both 2022 and 2023, Smithfield paid hundreds of millions of dollars in restitution to direct purchasers, retail consumers, and restaurant customers to resolve accusations of price fixing (Scarcella, 2023; CBS, 2022). In an ongoing suit against several U.S. pork producers and processors, Smithfield was alleged to have “kickstarted [a] conspiracy” that involved increasing exports to ratchet up domestic prices, where Smithfield “recognized that exporting more would reduce domestic supply, that the company sometimes exported at a loss to achieve higher meat value in the domestic market, and that Smithfield communicated the value of exports to help the domestic market with competitors” (In re Pork Antitrust Litigation, 2025, pp. 146-155). Another company Smithfield is alleged to have been cooperating with, Seaboard, put it succinctly in internal communications: “the more pork that moves out of the U.S., the better [i.e., higher] the domestic prices will be” (In re Pork Antitrust Litigation, 2025, p. 141).

The company also issued payouts for numerous lawsuits throughout the 2010s concerning reckless pollution of rural communities near its farms (Kite, 2022; Mishler, 2022). In one instance, a facility in Missouri—known for repeated contaminations of the nearby watershed—spilled 300,000 gallons of wastewater into nearby streams, turning the water “black and putrid” for miles. This incident was the largest within the context of 7.3 million gallons of such wastewater spilled over 30 years. Smithfield was fined for a similar case in Illinois in 2025 (Wells, 2025).

Smithfield, under its current ownership, has also failed to adhere to agreements with state governments for pollution management, facing over $470 million in penalties from a 2018 lawsuit brought by property owners in the vicinity of its plants (Derosier & Dalesio, 2018). Additionally, Smithfield settled a longstanding investigation in Minnesota over the use of child labor in one of its plants. As the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) announced in a 2024 press release,

DLI's investigation covered a two-year audit period [...] and found Smithfield employed at least 11 minor children between the ages of 14 and 17 during this time, three of whom began working for the company when they were 14 years old. [...] DLI also found all 11 minor children performed hazardous work for Smithfield, including: working near chemicals or other hazardous substances; operating power-driven machinery, including meat grinders, slicers and power-driven conveyor belts; and operating nonautomatic elevators, lifts or hoisting machines, including motorized pallet jacks and lift pallet jacks. (Minnesota DLI, 2024

Clearly, Smithfield has a proven track record of price fixing, cartel-like market manipulation, preferencing for the export market to China, reckless environmental behavior, and exploitation of child labor. Smithfield presents itself as a wholesome, American-owned and operated company. Meanwhile, it is 92.7% owned by the Chinese government, with profits channeled away from America. Together, these facts serve as a clear example of why stronger oversight and accountability in our food supply chain are urgently needed.

Syngenta’s Acquisition by ChemChina and the CCP’s Quiet Takeover Strategy

Syngenta Group is an agricultural chemical (agri-chem), seeds, and biotechnology business owned by ChemChina, a state-owned enterprise (SOE) of the PRC since 2017. In 2021, ChemChina merged with SinoChem, another PRC SOE, and is now the world's most extensive agricultural chemical and seeds supplier (AgroNews, 2021). Attempts at espionage and theft of America’s cutting-edge agricultural innovations, including proprietary seeds, by PRC agents have been documented as far back as 2013 (Dodson, 2023) and as recently as 2023 (Philips, 2023). Sinochem’s/ChemChina’s close ties to the PRC government have been known since the merger and were officially identified in an Executive Order (Executive Order No. 13959, 2020) promulgated by President Donald Trump on November 12, 2020.

Technically headquartered in Switzerland, the group has a significant presence in the United States, comprising dozens of individual corporations, both U.S.-based and foreign, that are engaged in import and export activities (Syngenta, n.d.-b). Syngenta and its affiliates produce crop protection products (e.g., herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides) with operations spanning the United States, Switzerland, the People’s Republic of China, and other countries. Despite acquisition by a Chinese SOE nearly a decade ago, many in the agricultural sector still perceive Syngenta to be Swiss-owned.

The Syngenta Group’s 2024 revenues totaled over $13 billion in the crop protection market. North America accounted for approximately 23% of its global revenues, while Latin America represented more than 36% (Syngenta, 2025a, p. 2). Syngenta’s self-identified “main production sites” are in Switzerland, the UK, the U.S., France, China, and Brazil. However, this list is misleading because Syngenta operates numerous subsidiaries and partnerships in China, in addition to its standard practice of divesting manufacturing sites to subsidiaries, many of which are not disclosed directly by the company.

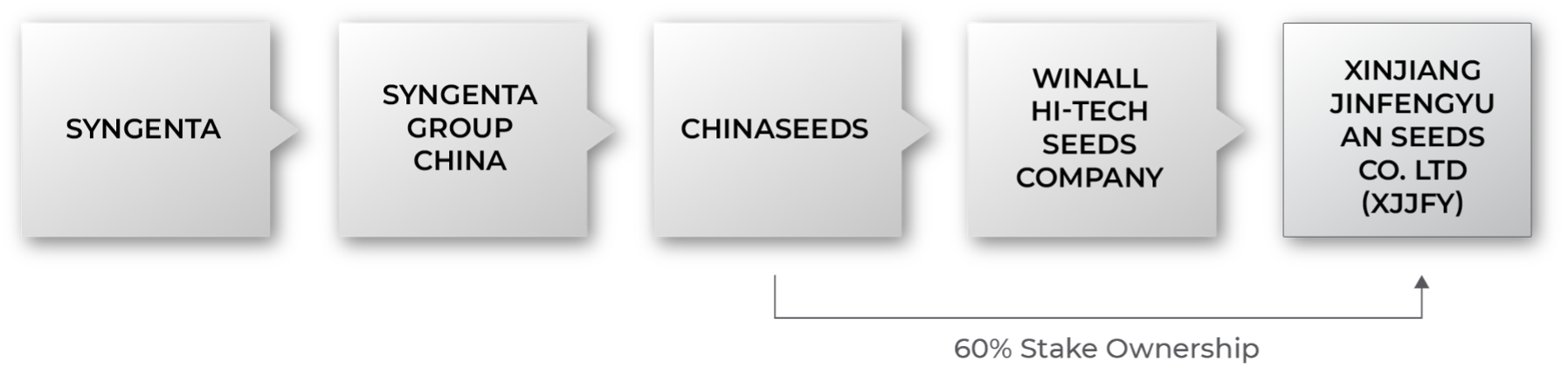

Especially disturbing is Syngenta Group’s alleged complicity in slave labor and violations of human rights. Syngenta’s China arm, Syngenta Group China, has a vast network of subsidiaries and constituent firms throughout the PRC, spanning the country. One such subsidiary is Xinjiang Jinfengyuan Seed Industry Co., Ltd, which is owned through a triple-layered structure: Syngenta Group China consolidated its (Syngenta, 2021) subsidiary Winall Hi-Tech Seeds Company into its ownership of Chinaseeds (Sinochem Group, 2023), which itself, as of 2021, owned a 60% stake (MarketScreener, 2021) in Xinjiang Jinfengyuan Seeds Co., Ltd. This ownership structure—subsidiaries nestled within nebulous ownership stakes and agreements—allows the activities of these companies to be more easily hidden. Syngenta profits massively from such obfuscation.

In effect, the ownership of Xinjiang Jinfengyuan Seeds Co., Ltd. (hereafter referred to as XJJFY) is as follows:

Figure 1 – Graphic representation of Syngenta’s ownership of XJJFY.

Disturbingly, Xinjiang Jinfengyuan Seeds Co., Ltd. had previously maintained a working relationship with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (hereafter referred to as XPCC). This U.S.-sanctioned, Chinese state-owned company has sometimes been likened to a “colonial” company or a “paramilitary corporate conglomerate.” XPCC has been identified as the primary violator of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) in Xinjiang (Murphy et al., 2022). XJJFY’s involvement with XPCC is evidenced in its 2015 financial report (Xinjiang Jinfengyuan Seeds Co., Ltd., 2016, p. 144), which includes the following:

“(3) Operational Capability Analysis

[…] The accounts receivable increased significantly at the end of July 2015, mainly because agricultural production is seasonal, with spring being the peak season for seed sales. To increase the market sales scale and enhance customer stickiness, the company provides different credit periods to customers based on their circumstances during sales. Among them, in January-July 2015, the company increased its sales efforts towards Bingtuan [XPCC], farms, and other direct procurement customers. In 2015, the company increased its sales efforts towards direct procurement customers such as Bingtuan and farms.” [MACHINE TRANSLATED][1]

While there has been a more recent disclosure of XJJFY’s collaboration with XPCC since the 2015 financial statement, there is no reason to believe these relationships have ceased. XJJFY’s primary business is selling seeds to farms in Xinjiang, and XPCC is one of the clients it has cultivated. As recently as 2022, XJJFY was explicitly identified as participating in collaborative efforts with numerous state-run universities in the Xinjiang region, with a focus on agricultural technology development (Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Xinjiang, 2022). The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) government, as the primary coordinator and facilitator of the agreement, is working directly with XJJFY, and consequently, with Winall Seeds, Chinaseeds, and Syngenta China. The XUAR, combined with the XPCC, contributes to the research and development of seed technologies through its well-documented forced labor practices, which are deeply integrated into global supply chains. Consequently, Syngenta is likely to profit or otherwise benefit from forced labor in the XUAR (Global Supply Chains, Forced Labor, and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, 2020).

The CCP was designated under the first Trump Administration as the overseeing political entity that organized the Uyghur Genocide in Xinjiang (Pompeo, 2021). The board of SinoChem Holdings (Sinochem Group, n.d.), under which Syngenta is organized, is under the implicit control of the CCP, as it is a state-owned enterprise and reports to a state-controlled board that supervises it. As Syngenta continues to expand its operations in the PRC—aiming to grow its farm count nationally from 600 to over 1,000 by 2026—its exposure to forced labor will only increase (Ng, 2024). This trajectory makes Syngenta not just an agricultural giant, but also a financial vehicle directly entangled with the CCP’s system of state-backed forced labor.

Drones and “Big Data Operations” Scrape American Data for the CCP’s Benefit

Aerial imagery data collection from drones, aircraft, and satellites is also beginning to dominate important facets of the agricultural sector, as massive conglomerates offer apps and innovative technologies (Syngenta, n.d.-a) to assist farmers with decision-making to maximize output and crop health. The integration of drones with the capability to collect large amounts of data from U.S. agricultural processes and feed it to Chinese firms poses serious risks. The raw photographs and video imagery gleaned could be used to construct, through “big data” computing and artificial intelligence, a massive, trained database and visual model that could identify any number of factors to maximize yields, such as: the performance of particular crop strains in particular soils or locations, unique threats from pests or disease, effects of weather, and other valuable features. All of this data would be fed to China’s government, shared among government agencies, and potentially weaponized against the United States.

For example, Syngenta has secured exclusive agreements with Chinese manufacturers to provide farmers with drones, enabling them to optimize yields through applications such as land surveying and pesticide spraying. Chinese drone manufacturer XAG has entered into agreements with Syngenta to provide drones to farmers in Ukraine (Velykyi, 2025). Similar agreements have been made between China’s top drone manufacturer, DJI, and Syngenta Japan and Syngenta Korea (DJI, 2019; DJI, 2020).

Similarly, DJI is actively seeking to expand into American agriculture and is now targeting American farmers at industry expos (DJI, 2025). DJI poses a particular threat due to its extensive ties to the CCP intelligence services. Multiple federal agencies have cautioned against the use of their drones. Despite a de facto ban on DJI in the U.S., the company’s products continue to be imported illicitly (Smalley, 2024; Hollister, 2025).

In addition to drones, Syngenta and Smithfield offer innovative “data tools” to their customers, which also serve as gatherers of proprietary information on American farm operations that is then transmitted to China. Both operate “big data operations” designed to collect, crunch, and iterate upon as much data as possible to improve their products for resale to the market. Syngenta’s “Cropwise” integrates everything from imagery to planting to seed selection, while Smithfield has introduced several data analytics and vision tools that collect valuable information from its facilities, such as hog health and behavior ( Businesswire, 2025; Smithfield, n.d.). In an era of artificial intelligence, large datasets and substantial computational power are required to train and iterate on such data. China has a unique ability to weaponize the data that America generates against us due to the state’s direct role in building capacity—in both data centers and power generation—for this purpose specifically.

It is crucial to note that even without integration into formal CCP or PRC ownership structures, companies operating in China may, at any time, be compelled to supply data to state authorities under China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law (U.S. DHS, 2020). The law also requires that any company operating in the PRC must create backdoors that Chinese state intelligence services can use in systems sold worldwide. The 2017 National Intelligence Law, combined with the Data Security Law of 2020, also creates a centralized data collection body in China and shares such data with all state agencies and obligates any firms performing “data activities” to “benefit the advance of economic and social development [and] conform to social morals and ethics” for the PRC’s benefit (Rafaelof et al., 2020).

Chinese Regulatory Bodies Leverage Import Approvals to Continue a Long Tradition of CCP IP Theft

There is a long-term pattern of Chinese SOEs purchasing stakes in foreign companies and then extracting their intellectual property. IP transfers to Chinese companies frequently occur under the guise of technology sharing, licensing, or via partial ownership arrangements, and Chinese involvement in America’s agricultural industry also indicates similar risks.

For example, focused efforts have previously targeted the aviation industry, as seen in the case of ICON Aircraft (Aero News, 2024), in which IP theft ran the company into bankruptcy, and Cirrus Aircraft (Schramek, 2023; McKellar, 2025), where a major civil-military fusion Chinese SOE now owns the company. Numerous other examples have been documented by the United States government in both congressional and executive reports, with theft occurring through various methods, including forced joint ventures, research partnerships, the purchase of shares to appoint board members, and other corporate oversight measures (O’Connor, 2019).

In perhaps the most telling and high-profile example, Westinghouse Electric was compelled to form a joint venture with a Chinese company as part of its bid to sell nuclear reactors in the Chinese market in the 2000s. As former United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer explains, this was the beginning of a disastrous partnership:

The experience of Westinghouse Electric Company provides a great illustration of all these dynamics. When Westinghouse executives sought access to the Chinese nuclear power plant market in the early 2000s, they had to sign a joint venture agreement with China’s leading nuclear power state-owned company – China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) – to jointly build Westinghouse’s AP-1000 reactors. The agreement entailed both technical assistance and the exchange of thousands of documents on nuclear power plant design. In one fell swoop, China received the details of decades of U.S. nuclear power research. What little China could not get through this deal, it simply stole. In 2010, hackers within the Chinese military penetrated Westinghouse systems and stole confidential, proprietary technical and design specifications for the AP-1000 plant. These hacks, according to the Department of Justice, ‘would enable a competitor to build a plant similar to the AP-1000 without incurring significant research and development costs.’ Within a decade of forming its Westinghouse partnership, CNNC unveiled its own Hualong One nuclear power reactor, which bore striking resemblance to Westinghouse’s AP-1000 [emphasis added]. Today, Westinghouse makes no nuclear power plants or reactors for the Chinese market. Meanwhile, CNNC – powered by Westinghouse technology – competes at the heights of the global nuclear power market. (Lighthizer, 2023)

Westinghouse ultimately went bankrupt in 2017, affecting only U.S. operations (Nakano, 2017). The new Hualong reactor model enabled China to leapfrog and detach from additional business with Westinghouse and most Western nuclear technology firms more generally (Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2018). This institutional system of intellectual property theft was explicitly established to use the knowledge of foreign corporations to strengthen or improve the Chinese industry. When such arrangements, either openly or illicitly, have been exploited to their fullest extent, the CCP will then create its own self-sufficient and home-grown version to compete and ultimately eject foreign competition.

This pattern extends to China’s leveraging of regulatory authority over agricultural companies to extract valuable IP from U.S. firms. China, like all countries, exercises its prerogative to establish regulatory regimes to govern business and foreign dealings. However, China’s agricultural import regime is particularly susceptible to manipulation due to the complex nature of Chinese import law and the special approvals required for importing certain chemically or genetically altered foods and products derived from genetically modified seeds. Syngenta and Smithfield are likely to be treated more favorably by the People’s Republic of China because of their ownership, and they may tailor their operations specifically to meet the needs of the PRC market.

This unequal playing field is especially devastating for American soybean and corn farmers, as these crops are among the most valuable U.S. agricultural exports. When prepared for foreign export, multiple varieties of American corn from different growers are mixed, as “the USA does not have any mandatory mechanism in place to separate out or label [genetically modified] and [non-genetically modified] corn for export purposes” (Panel Established Pursuant to Chapter 31 United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, 2024, p. 14). Once the corn, or any similar product, is shipped to the foreign market, it is no longer feasible to determine the product mix. If a foreign purchaser, such as China, has not approved a genetically modified strain of corn and some of the unapproved corn is present, they may reject the entire shipment. For example, in 2013, the export of a quantity of MIR162 (a genetically modified strain of corn, engineered by Syngenta while they were still Swiss-owned, and designed to be insect-resistant) angered Chinese officials, who had not cleared the product for import into the PRC (Schmitz, 2018, pp. 1-2). By November 2013, China had placed an embargo on any corn exported from North America, “which was not lifted until December 14, 2014 […which led] to a reduction in the price of corn” and subsequent market losses for many smaller, independent farmers (Schmitz, 2018, p. 2).

Indeed, China’s onerous regulatory process can sometimes be so burdensome that companies subject to it may wait for years. As one team of researchers found, the average time for import approval of genetically modified crops was typically received “on average 1544 days (4.2 years) after it has been approved in the USA, and 1783 days (4.9 years) after approval in Canada” (Jin et al., 2019). The long waits for approval in China could feasibly be shortened if the regulators wished, because the relevant Chinese ministries and agencies already have access to “a large proportion of the required information [which] is generated in the country of first submission, the USA” (Jin et al., 2019). This allows China to freeload on much of the regulatory work, but it still insists on creating additional bureaucracy for unclear reasons. This process involves numerous rounds of testing. Some tests are directly supervised by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA). In contrast, others are carried out on external farms, or are allocated to “research institutions or universities assigned by MARA [to] conduct food safety tests” (Jin et al., 2019).

As one paper explains,

[Any particular genetically modified crop variety] must go through an extensive Chinese regulatory process in order to be approved for export to China. The initial application must include biosafety approval from the country of origin. Upon reviewing the application, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture (MOA) undertakes its own biosafety evaluation […] Companies must apply for a seed import license, in both the local provinces and the MOA’s seed division, and then go through a quarantine inspection process which normally takes 4 to 6 months [alongside further environmental and localized, randomized testing]. (Schmitz, 2018, p. 2)

Such permitting has previously been used as leverage in trade talks between the U.S. and China (Patton, 2019). China may be incentivized, given its demonstrated capacity to use these approvals as trade leverage, to delay import approvals and hinder the ability of competing firms to ramp up production. Thus, the uncertainty introduced by China’s import approval system inhibits the U.S. agricultural biotechnology sector and introduces tremendous instability into the entire value chain.

Additionally, China’s regulatory model for importing crops produced from new genetically modified seeds has a significant influence on the global market and has been weaponized to frustrate biotech trait developers based in the U.S., who compete with Syngenta. Previous annual assessments by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) have identified China’s occasional refusal to actively utilize testing data from other countries (Foreign Agricultural Service, 2019, p. 4), apparently as a tactic to punish certain companies or countries. Simultaneously, it may co-opt this data to accelerate its processes and opportunistically engage in IP theft.

In fact, the CCP’s ownership of a leading firm in the sector is an inherent conflict of interest. The CCP is responsible for collecting proprietary samples and requesting large amounts of technical data on products that compete directly with Syngenta (Foreign Agricultural Service, 2024, pp. 2-6). The Chinese government has a long, well-documented record of encouraging domestic enterprises and institutions to “[support] the acquisition of biotechnology” as part of several of the CCP’s multi-year economic plans (Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2017, pp. 124-128). Chinese universities have also played a crucial role in receiving stolen or forcefully transferred intellectual property and trade secrets (Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2017, p. 109; United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, 2019, pp. 72-74).

China has demonstrated a willingness to conduct such activities not only on its soil, but also on American soil. Two cases in the last decade have demonstrated that Chinese nationals have been involved in international corporate espionage, specifically in the agricultural sector. In one case, a lawful permanent resident Chinese national, employed as a director at a Beijing-based conglomerate with agricultural interests, pleaded guilty to attempting to steal trade secrets, including seeds, from companies such as DuPont and Monsanto, using farms that he owned in Iowa and Illinois (U.S. DOJ, 2016). In a second case, again targeting Monsanto, a Chinese national who was an employee attempted to flee to China with digital copies of Monsanto’s intellectual property relating to data analytics for maximizing farm yields in what the Department of Justice called a “danger to the U.S. economy [and] our nation’s leadership in innovation” (U.S. DOJ, 2022). In the latter case, the Chinese national was also an employee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Soil Science—a university closely associated with the Ministry of Agriculture.

China Leverages State-Owned Enterprises for Market Dominance

China, through its SOEs, has a deliberate strategy of overseas acquisitions to dominate entire technology sectors. The Chinese state and the CCP both guide SOEs in business strategy, development, investment, and acquisition to further their goals of sectoral control. Preferred access to state financing and China’s huge consumer base have yielded a massive advantage for Syngenta—one that tends towards consolidation. Syngenta’s preferential treatment by the Chinese government is best exemplified by its first-in-line access to selling staple GMO crop seeds for cultivation in China (Yeh, 2023; Reuters, 2022). This preferential treatment is also reflected in the corporate strategies of ChemChina and Syngenta. For example, ChemChina's strategy of acquiring agricultural firms increasingly forces competitors to either sell out to them or be acquired by other competitors, a consolidation problem that has been ongoing since the 2000s (Lucas, 2008). Further mergers in the 2010s worsened this problem, which was only partially mitigated by many anti-trust measures from the U.S., the European Union, and Brazil (MacDonald, 2019).

China’s strategy of using SOEs such as Syngenta to control strategic aspects of the agricultural sector has already instigated U.S. government intervention. The director of Syngenta China has publicly admitted China’s vision, stating to China Daily in 2018 that “[Syngenta] now [has] an owner who understands the strategic importance of agriculture in China and globally, and who takes the long-term view” (Zhong, 2018). Market consolidation has become such an acute concern that when ChemChina acquired Syngenta, the U.S. compelled Syngenta to divest from several pesticide products to prevent monopolization. This was necessary because a separate subsidiary of ChemChina was Syngenta’s only competition in producing several ubiquitous chemical products, such as paraquat (Federal Trade Commission, 2017).

This is further exemplified by Syngenta’s purchases in the realm of biotechnology. In 2020, Syngenta acquired a “biologicals” (a catch-all term for crop protection and related products) company, Valagro, saying that the acquisition was motivated by a desire to “shape the rapidly growing Biologicals market” (Syngenta, 2020). In February 2025, Syngenta purchased the biologicals repository of Swiss-owned Novartis for agricultural use, which Syngenta claims “gives [...] access to an important source of novel leads for agricultural research” (Syngenta, 2025b).

Similarly, Smithfield’s status as a proxy of a Chinese SOE gives it the power to game regulations to its advantage. Imported pork products face a similarly onerous approval process to agricultural products, particularly as it relates to added hormones and chemicals in pork feed (Switzerland Global Enterprise, n.d., p. 2), but Smithfield’s conformity to Chinese pork requirements effectively shields it from regulatory scrutiny. Meanwhile, Smithfield's scale provides it with a competitive advantage in placing its product with Chinese retailers. For example, it has a lucrative contract with Jingdong, China's second-largest e-commerce service (Jingdong, 2017).

Additionally, China’s status as one of the largest purchasers of miscellaneous pork products (Polansek, 2025) gives it the ability to use tariffs and/or purchase commitments on the United States to exert pressure on American markets. Given a scenario where China raises agricultural tariffs on the United States, Smithfield could plausibly receive preferential treatment in imports. At the same time, other U.S.-based companies would likely face the full tariff or decreased purchase amounts. Smithfield’s market saturation means that even if it did suffer under a Chinese tariff regime, China could find domestically operated substitutes for pork producers. At the same time, the United States would have nearly one-fourth of its market operated by a Chinese owner.

CCP-tied Enterprises Meddling in American Politics

Both Smithfield and Syngenta, despite being principally owned by Chinese corporations, routinely lobby U.S. government agencies without registering as foreign entities. Smithfield denies qualifying as a Chinese-controlled entity, claiming that WH Group “is not a Chinese state-owned enterprise and does not undertake any commercial activities on behalf of the Chinese government” (Faleski, 2024; Peng, 2025). In January 2025, Syngenta stated to Mother Jones that it is “independent” and “not a Chinese military company, nor do we have any association with the Chinese military” (Choma & Friedman, 2025).

Smithfield’s claim is technically correct in that it is not a Chinese state-owned enterprise; rather, it was purchased in 2013 by WH Group, a Hong Kong-registered pork trading group with CCP party members serving as the board chairman and in four other board positions (Lenczycki, 2024). Smithfield is now listed on the NASDAQ, but, as stated before, it is 92.7% owned by Hong Kong’s WH Group. In 2017, Syngenta was acquired by ChemChina, a state-run chemical and petroleum conglomerate. Therefore, it is wholly and exclusively responsible to the CCP and the Chinese state. Syngenta’s claim to not be a “Chinese military company” rings hollow, as they are a direct subsidiary of ChemChina, which is listed on the DOD’s 1260H Chinese Military Companies list (Department of Defense, 2024). The United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission noted in a 2013 report that the original Smithfield purchase involved preferential financing and Chinese state subsidies. In addition, “Chinese companies seeking to invest [or purchase] abroad must first receive government approval” (Slane, 2013, pp. 1-2). Only under the most evasive interpretations could both companies claim to be independent.

At the same time, the Chinese government keeps a close eye on and uses a heavy hand with its SOEs and their overseas activities. As Dr. Nikolaus von Jacobs and Ding Han of McDermott Will & Emery report, SOEs are legally required to report any overseas acquisitions to the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (von Jacobs & Han, 2019). “Private” companies operate under similar requirements, such as reporting to the National Development and Reform Commission. The USDA noted in a 2018 report that the CCP was repeatedly encouraging overseas investments in agriculture throughout the 2000s and 2010s; in short, these overseas purchases were at least in part guided and encouraged by the CCP and likely received specific permission from them, and they were not independent commercial decisions (Gale & Gooch, 2018). As research from the National Bureau of Economic Research has shown, even former SOEs “[still] enjoy lower interest rates, larger loan facilities, and more subsidies while suffering poorer performance [i.e., remnants of government inefficiency] than never-SOEs” (Harrison et al., 2019, p. 3).

Since Syngenta’s first full year of ownership by ChemChina (2018), they have paid over $8 million for federal lobbying, and in the near decade of WH Group’s (2016) ownership of Smithfield, they have paid over $11 million for their own lobbying efforts (Secretary of the Senate, 2025a; Secretary of the Senate, 2025b).

The first Trump administration pursued the most consequential tariff and trade policy reforms in a generation, aiming to radically alter the economic and strategic dynamics between the U.S. and China. In 2018, then-United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer imposed tariffs on $370 billion of imported Chinese goods under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to penalize the PRC for its unfair practices, including forced technology transfer and intellectual property theft. In 2019, comprehensive trade negotiations began between the PRC and the United States to resolve duties imposed as a consequence of the Section 301 investigation, ultimately culminating in the Phase One trade deal in January of 2020.

Within this context, Syngenta and Smithfield lobbied key elements of the federal government on issues with direct bearing on China’s economic destiny. They were spurred into action precisely because the first Trump Administration was seeking to initiate unprecedented economic penalties against China. In the second quarter of 2018, Syngenta lobbied the Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Commerce regarding the initiation of Section 301 and Section 232–national security duties previously used on industrial goods such as steel, aluminum, and automobiles–tariffs, with the first tranche of Section 301 tariffs (meant to punish countries engaged in unfair trade practices) on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese exports implemented in July 2018. Then, in the second quarter of 2020, Syngenta lobbied the United States Trade Representative (USTR) and USDA on “issues related to US-China Phase One Economic and Trade Agreement.” A key element of Phase One was an obligation for China to increase U.S. agricultural product purchases by $40 billion annually over the course of two years. Smithfield also directly approached USTR regarding the Phase One deal, which included provisions related to the exportation of American-raised pork to China (Secretary of the Senate, 2018; Secretary of the Senate, 2020).

Smithfield and Syngenta are arguably in violation of the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938 (FARA), as they have neither registered as foreign agents nor disclosed their lobbying activities in the nation’s capital while serving as de facto agents of the Chinese government, being Chinese-owned corporations. FARA was passed nearly a century ago to protect the American people from exactly such malign foreign influence. The act was originally written to expose Nazi influence within German-American organizations in the lead-up to World War II (Straus, 2020). FARA prohibits persons from advocating or lobbying for the interests of foreign nations in the United States without prior registration and disclosure. It requires that anyone who wishes to advocate for foreign interests declare their relationships to the Department of Justice (DOJ) and disclose the type of business and agreements they have with foreign principals (i.e., governments, organizations, or other represented interests), including financial transactions and identifying information. They must also specify the topics or issues they are lobbying on.

CCP Corporate Land Ownership: Platforms for Surveillance and Sabotage

The land that these Chinese-owned American companies control represents another dangerous facet of this national security challenge. American real estate serves as a forward operating platform for surveillance and sabotage, and it also facilitates CCP IP theft directly on American soil. The Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act (AFIDA) report of 2023 found that Chinese nationals or companies with primary Chinese ownership (i.e., the company is 50%+1 owned by a Chinese entity) owned 277,336 acres of agricultural land in the United States, including the following:

- Murphy Brown LLC / Smithfield Hog Production Division held 89,218 acres, primarily in North Carolina (37,515 acres) and Missouri (36,697 acres). Of this acreage, 458 new acres were disclosed in the 2023 filing season.

- Syngenta Seeds, LLC held relatively small amounts in several states, including Arkansas (160 acres, but this has since been divested under state law), California (48 acres), Colorado (150 acres), Florida (139 acres), Idaho (147 acres), Illinois (220 acres), Indiana (195 acres), Iowa (562 acres), Kansas (160 acres), and Minnesota (442 acres).

- U.S. Agri-Chemicals Corp., acquired by Sinochem in 1989 (Journal of Commerce, 1988), owns and operates 11,263 acres, exclusively in Florida’s Hardee and Polk counties.

It is important to note that this recorded acreage represents an absolute minimum estimate of land controlled by Chinese-owned or directed companies. As the report itself cautions,

If investors from multiple countries are listed on the [AFIDA filing] form, and the primary shareholding country cannot be determined, the holding is recorded as “no predominant country.” As a result, the acreage associated with China—or any other country discussed in this report—should be interpreted as a minimum. (Farm Service Agency, 2024, p. 5)

Adversary ownership of land in critical locations poses a special national security threat. China’s purchase of Smithfield immediately granted WH Group access to large tracts of land in the states of North Carolina, Virginia, and Missouri, all of which are home to significant military presence. Recent conflicts have shown that even the smallest parcels of land can serve as launchpads for devastating attacks. In Ukraine, drones were pre-positioned close to military bases and destroyed billions of dollars in Russian nuclear-capable aircraft (Mazhulin et al., 2025). Israel used unmonitored properties in Iran to assemble drones that then disabled large amounts of Iran’s air defense and missile systems (Motamedi, 2025).

Land ownership also gives Chinese companies the potential to introduce dangerous pathogens that could threaten the U.S. food supply chain. This would constitute a strategic weapon, especially in the case of a potential outbreak of hostilities between the two nations. This vulnerability was demonstrated vividly in June 2025 when two foreign Chinese researchers at the University of Michigan allegedly smuggled samples of Fusarium graminearum—a toxic fungus considered a potential agroterrorism weapon—into the U.S. via a concealed package (Creitz, 2025). The pathogen is responsible for head blight, a disease devastating to wheat, rice, and barley crops. It also produces toxins harmful to humans and animals.

A similar incident occurred at the University of Michigan just a week later, as federal authorities arrested a Chinese researcher on exchange from Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, and charged her with smuggling and making false statements (Winter & Jett, 2025). The researcher sent undisclosed samples of roundworms, concealed in several packages, to individuals at a university lab. The researcher had also wiped her digital devices before travelling to the United States, only admitting that she had sent the packages after an interview in custody.

PRC ownership of U.S. real estate is an immediate threat to national security due to its potential proximity to vulnerable sites critical to military and civil resiliency. Ownership of farmland provides access to proprietary seed and agrichemical technologies, opening a prime avenue for IP theft. Finally, allowing CCP agents access to agricultural land provides a vector of agricultural terrorism

Conclusion

The PRC is keenly aware that the continued productivity of the U.S. agricultural sector is crucial for American prosperity and food security. Chinese SOEs' quiet acquisition of companies critical to the sector, such as Syngenta and Smithfield, provides an important avenue for PRC malign influence.

Data gleaned from Syngenta’s operations and then fed into SinoChem's agricultural data services businesses has the potential for mass data harvesting, making its ownership strategic for China’s long-term goals in the industry. The CCP’s economic planning board in its Five-Year Plans directed agricultural companies, both state-owned and private, to go abroad and acquire assets in the global agriculture industry. The overarching purpose was for Chinese firms to increase China’s agricultural self-sufficiency through market consolidation and the transfer of intellectual property and industry best practices. Smithfield’s dominance over the pork sector and its strategic bifurcation of sales between the domestic market and the Chinese market give it undue influence over the industry. Additionally, its Chinese ownership potentially allows for strategic destabilization of food markets in times of conflict.

When the PRC acquired Syngenta and Smithfield in the 2010s, the U.S. government and civil society were not as attuned to the threat posed by China; as a result, these agricultural giants have thus far evaded the laws and regulations intended to protect the American people. They successfully cleared the CFIUS process and have been able to skirt registration requirements under FARA.

Since then, the American understanding of the whole-of-society threat posed by the CCP has matured, and the U.S. government's response has evolved. President Trump’s first term marked the first strategic use of tariffs and commercial restrictions to alter the strategic balance between the world’s two largest economies. In 2018, CFIUS saw significant reform in the shape of the Foreign Investment Risk Review and Modernization Act (FIRMMA), which would have substantially changed the factors taken into account had Syngenta and Smithfield filed their purchases after its implementation. The Biden Administration largely maintained Trump’s trade measures and added more restrictions on high-tech exports, and imposed tariffs on PRC electric vehicles. The second Trump Administration has seen a massive acceleration of measures meant to punish the PRC’s unfair trading practices and IP theft.

If the Smithfield and Syngenta acquisitions were re-initiated today, they would almost certainly not be accepted under the same terms.

Policy Recommendations

We recommend the following policies to resolve this security threat:

CFIUS Review and Re-Evaluation: CFIUS should re-review the purchases of both Syngenta and Smithfield—and any Chinese SOE purchases—with special consideration for market consolidation, food security, national security risks, and threats to proprietary information and consumer data. Furthermore, adversarial countries should be prohibited from using the “declaration” (also known as the “short-form”), which is an expedited filing process with CFIUS.

Mandatory FARA Registration: Chinese-owned businesses should be considered agents of a foreign government for FARA, and their registration should be mandatory. All PRC companies are subject to the National Intelligence Law of 2017 and the Data Security Law of 2021, and function as de facto arms of the Chinese state. Companies that are principally Chinese in their operations or governance but are headquartered in third countries should be considered principally Chinese-operated and should also be required to register with the Department of Justice under FARA.

Domestic Divestiture: Both Syngenta and Smithfield Foods should be compelled to divest to a domestic company or, at a minimum, a company not principally managed by an adversary of the United States.

Enforce the UFLPA: Syngenta Group China’s apparent collaboration with XPCC violates the UFLPA and necessitates investigation. Syngenta’s subsidiary XJJFY liaises with XPCC, which is named in the UFLPA’s text as a principal perpetrator and continues to be listed as a violator of the UFLPA by the Department of Homeland Security. Syngenta products should face importation bans or restrictions in the U.S.

Ban CCP Drones: Measures should be taken to prevent the widespread adoption of Chinese-manufactured drones for use in American agriculture, such as the Countering CCP Drones Act.

Protect U.S. Land: Legislation at the federal and state levels should be enacted to restrict foreign adversaries from controlling American farmland.

Farm Security is National Security: The USDA’s National Farm Security Action Plan should be implemented to its full extent. This would include the following measures:

- AFIDA reporting methods should be modernized, and its penalty schedule should be updated to provide an effective deterrent.

- America’s agricultural supply chains should be assessed for excessive foreign reliance.

- Agricultural research enterprises, particularly with public funding, should have higher security standards and provide more value to America’s farmers and ranchers.

- USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service should apply increased scrutiny to foreign importers from foreign adversary nations.

- The USDA should support the digital and operational infrastructure of agricultural firms to help businesses protect themselves from cyberattacks and other online threats.

- Research security and infrastructure security provisions should be maximized with increased funding and authorities given to the USDA.

[1] Original, untranslated text found on page 144 reads: “2015年7月末公司应收账款增长较多,主要系农业生产具有季 节性,春季属种子销售旺季,为增大市场销售规模,增强客户采购黏性,公司会 在销售时根据客户情形给予期限不等的信用期。2015年度,公司加大了兵团 [bingtuan, AKA XPCC] 、农 场等直采客户的销售力度,给予的信用期限较长,造成2015年7月末应收账款回 款金额相对较少。”

Works Cited