Are the ‘Studies’ Worth Studying? A Cross-department Comparison of Academic Rigor at The University of Texas at Austin

Key Takeaways

The “Studies”—e.g., “Women’s Studies,” “Asian American Studies,” “Critical Disability Studies,” etc.—are activist rather than scholarly disciplines.

The Studies are also much less rigorous than other disciplines, including the social sciences, and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

Simple, “low hanging-fruit” remedies to grade inflation include eliminating low-rigor disciplines (such as the Studies) and capping “A” grades at the class and department levels.

Congress and the Department of Education should require colleges and universities to report mean student SAT and ACT scores by major at the degree level to enable better comparisons of rigor by discipline.

Introduction

In competitive environments, a common dictum holds: “They can’t all be winners.” University grading seems to defy this rule. During the last three decades, grade point averages (GPA) rose 17% at four-year public universities and 16% at private non-profit universities (Nam, 2024). Grade inflation diminishes the value of grades as repositories of information pertaining to academic quality. This, in turn, harms universities’ pedagogical and professional missions. When excellent students are indistinguishable from merely competent students, student achievement wanes, and universities (e.g., graduate admissions officers) and prospective employers are forced to evaluate applicants by other means (Arum & Roksa, 2011; Nickolaus, 2024; Cerullo, 2023).

Student migration into less rigorous courses and disciplines contributes to grade inflation (Hernandez-Julian & Looney, 2016). Several notoriously lax-grading disciplines, collectively known as “the Studies,” have well-earned reputations for prioritizing activism over scholarship (Bawer, 2023). As described in this report, the Studies’ strong ideological and activist commitments could contribute to lax grading by creating alternatives to traditional assessments of academic quality. Increased enrollment in the Studies would, therefore, tend to harm overall (university-wide) grading rigor (hereafter, “rigor”).

This report investigates this possibility at the University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin), a large public university. It presents findings from an analysis of 10 semesters of grades obtained from 21 disciplines spanning three fields of study: the Studies, the social sciences, and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). It finds the Studies to be considerably less rigorous than comparison fields. When considered alongside longstanding concerns regarding the limited intellectual merits of these disciplines, these findings raise serious doubts as to the value of continuing to host these disciplines. This report concludes with several recommendations for improving rigor in higher education.

Rigor and Grade Inflation

What does an “A” grade signify in a university setting? How does it differ from a “B” or a “C,” for instance? Universities sometimes provide official answers to these questions; however, most students and faculty know grading rigor often differs by course, department, and field.

Academic rigor is closely related to grade inflation, the tendency for grades to increase over time. Grades have been likened to a currency in that, much as the value of the dollar depreciates overtime due to increases in the money supply, the value of a given grade (e.g., an “A”) and high GPAs depreciate overtime due to the proliferation of higher grades. The primary culprit for grade inflation appears to be increasingly lax grading in response to “consumer demand” from students and parents; however, changes in student quality and student self-selection into easier-grading courses are contributing factors as well (Rojstaczer, 2023; Hernandez-Julian & Looney, 2016).

Rigor describes the setting and maintaining of high standards to preserve the value of grades against inflationary pressures.[1] The failure to maintain rigor undermines the usefulness of grades as signals of academic quality—i.e., subject matter mastery, diligence, and skill. The proliferation of “A” grades in undergraduate settings complicates efforts by employers and graduate admissions officers to separate the academic wheat from chaff, forcing them to rely on other metrics (Nickolaus, 2024; Cerullo, 2023).

Failing to maintain rigor also reduces student learning by removing a key impetus for course mastery. As described in an internal Yale University memo, compromising rigor results in “students who do exceptional work [being] lumped together with those who have merely done good work, and in some cases with those who have done merely adequate work” (Mayhew, 1993). Students appear to be studying and learning less than in years past, yet grades continue to rise year-over-year (Babcock & Marks, 2010; Arum & Roksa, 2011). This paradox suggests the failure to maintain rigor has harmed student learning while also distorting the economy of academic grading.

Most research in this area addresses declining rigor over time (grade inflation); however, removing the time dimension can help to illuminate other important factors. For example, the natural sciences and math are typically more rigorous than the social sciences, which, in turn, are more rigorous than the humanities (Achen & Courant, 2009; Rojstaczer & Healy, 2010). Students appear to recognize this pattern insofar as self-selection into less rigorous disciplines is among the drivers of grade inflation (Hernandez-Julian & Looney, 2016).

The Studies

One field of study—the Studies—deserves special attention. The Studies are a collection of relatively new academic disciplines such as “Women and Gender Studies,” “African American Studies,” “Mexican-American / Latin(o/a/x) Studies,” and so on.[2] The Studies have been criticized for prioritizing political and social activism over rigorous scholarship (Ginsberg, 2025; Schalin 2025).

As discussed further below, this reputation makes the Studies a presumptive target for investigations of rigor and/or grade inflation. The Studies often fare poorly in cross-department comparisons. For example, “Afroamerican and African Studies” and “Women’s Studies” ranked 14th and 21st out of 25 departments respectively in terms of rigor at the University of Michigan from 2005 to 2007 (Achen & Courant, 2009). More recently, an internal Yale College report uncovered that “Women, Gender, & Sexuality Studies” awarded “A” grades to 92% of students in introductory courses.[3] “African American Studies” (82.2% “A”), “Regional Studies” (82.7% “A”), “Ethnicity, Race, and Migration” (85.4% “A”), and “Education Studies” (85.8% “A”) followed closely behind (Fair, 2023).[4]

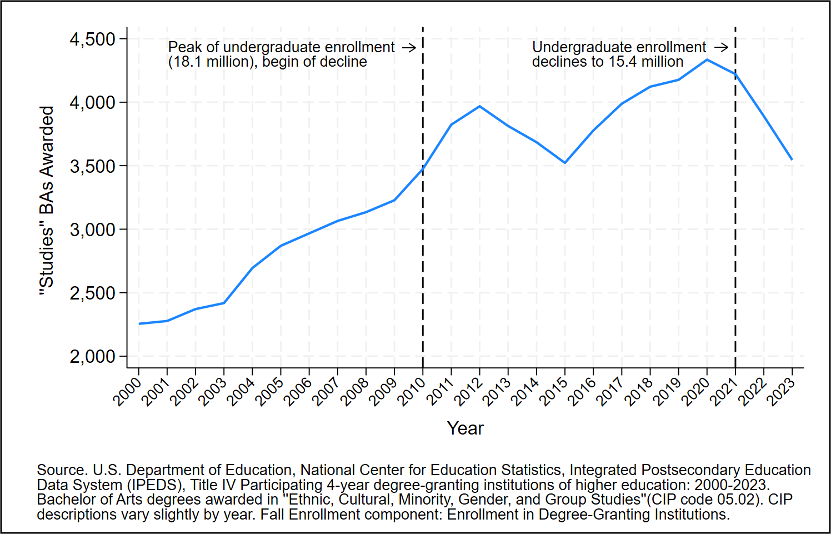

These examples notwithstanding, the question of rigor in the Studies has not garnered extensive attention through the traditional approaches to academic investigation.[5] There are at least two explanations for this apparent oversight. The first has to do with the Studies’ potentially limited impact on overall university rigor. Across Title IV eligible, degree-granting, four-year colleges and universities in 2023, 3,545 fulltime eligible (FTE) students obtained bachelor’s degrees in Studies disciplines in comparison to 131,719 FTE students who obtained bachelor’s degrees in psychology.[6]

Though reasonable sounding, it would be a mistake to ignore the Studies on such grounds. According to a recent report by the National Women’s Studies Association (NWSA), undergraduate enrollment in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies increased in half of 244 surveyed departments from 2018 to 2023 (Clark-Taylor et al., 2024). Similar trends are evident across the Studies writ large. As depicted in Figure 1, the number of Studies bachelor’s degrees increased 57% (2,255 to 3,545) from 2000 to 2023 (National Center for Educational Statistics, n.d.-c). This expansion is remarkable given that national student enrollment declined by 2.7 million (15%) during the latter half of this same period (National Center for Education Statistics, 2023). In short, the Studies are a small but rapidly growing field. Their impact on overall rigor is likely to increase.

A second likely explanation for researchers’ apparent disinterest in the question of rigor in the Studies concerns sensitivities associated with the topics addressed by these disciplines. For example, researchers may feel that investigating African American Studies could be interpreted (or misrepresented) by colleagues or students as signaling hostility towards African Americans. The same is true for Women’s Studies, LGBTQ Studies, Mexican-American/Latin(o/a/x) Studies and so on, perhaps excepting Whiteness Studies and American Studies, given that these disciplines are uniquely oriented against the groups they study (Lindsay, 2020; Fluck & Claviez, 2003).

If such concerns present a barrier to investigating rigor in the Studies, this barrier must be overcome. Desiring to avoid offense is commendable and desiring to preserve one’s career and relationships is understandable; however, the question of rigor in the Studies remains to be explored. Real or feigned offense and any social costs to academic investigation are simply irrelevant to the merits of the topic.

Why Might the Studies Lack Rigor?

As noted, the Studies are often held in low regard by their peers in the academy. This is true even among their politically sympathetic peers (Paglia, 2018; Sommers, 2021). The cause for this low regard lies in the widespread perception that these disciplines prioritize (invariably, left-leaning) political activism over the pursuit of knowledge. Is such criticism fair? Consider the following:

- The NWSA defines its mission as “further[ing] the social, political, and professional development of Women's Studies throughout the country and the world, at every educational level and in every educational setting.” In the preamble of its constitution, the NWSA declares its commitment to “a world free from sexism and racism,” “national chauvinism, class and ethnic bias, anti-Semitism, as directed against both Arabs and Jews; ageism; heterosexual bias” and “from all the ideologies and institutions that have consciously or unconsciously oppressed and exploited some for the advantage of others.” The NWSA then rejects “the sterile division between academy and community,” an apparent reference to the distinction between scholarship and activism, and embraces a role of “transform[ing] the world” to one “that will be free of all oppression” (NWSA, 1982).

- The University of California, Berkely, describes its Chicanx Latinx program as “grounded in the decolonization and liberation projects of U.S. Latina/os and their allies in the civil rights, gender, and sexual liberation movements of the 1960s that continue through the present in new forms that address new conditions.” It further calls out “the limited scope of Eurocentric or other ethnocentric perspectives and the disciplinary constraints in traditional fields of the humanities and social sciences” (UC Berkeley, n.d.). This is yet another apparent reference to the scholarship/activism distinction.

- According to one if its most influential scholars, Critical Whiteness Studies (CWS) aims to “reveal the invisible structures that produce and reproduce white supremacy and privilege. CWS presumes a certain conception of racism that is connected to white supremacy.” CWS advocates “vigilance among white people” in combatting white privilege, asserting that white supremacy in America will endure unless whites acknowledge their (inherent) complicity in racism (Applebaum, 2016). “Race Traitor,” a former Whiteness Studies journal declared in its headline, “Treason to whiteness is loyalty to humanity.” Its first issue led with an editorial titled, “Abolish the White Race by Any Means Necessary” and included such entries as “The American Intifada” and “The White Question” (Garvey & Ignatiev, 1993).

Similar descriptions attend other Studies departments, including African American/Black Studies, American Studies, and Asian American Studies (Hine, 2014; Fluck & Claviez, 2003; Association for Asian American Studies, n.d.). By contrast, the American Political Science Association (APSA) describes political science as “The study of governments, public policies and political processes, systems, and political behavior.” It further states,

Political science subfields include political theory, political philosophy, political ideology, political economy, policy studies and analysis, comparative politics, international relations, and a host of related fields… Political scientists use both humanistic and scientific perspectives and tools and a variety of methodological approaches to examine the process, systems, and political dynamics of all countries and regions of the world. (American Political Science Association, n.d.)

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) describes psychology as “the study of the mind and behavior,” adding,

The practice of psychology involves the use of psychological knowledge for any of several purposes: to understand and treat mental, emotional, physical, and social dysfunction; to understand and enhance behavior in various settings of human activity (e.g., school, workplace, courtroom, sports arena, battlefield); and to improve machine and building design for human use. (APA, 2018)

Like their peers in the Studies, U.S. political scientists and psychologists lean strongly to the political left. For example, among full-time Ph.D.-holding professors at liberal arts colleges, registered Democrats outnumbered registered Republicans 8.2 to 1 among political scientists and 16.8 to 1 among psychologists (Langbert, 2018). This stark disparity is in no way indicated by the APSA or APA’s descriptions of their respective fields. This is not to say that political scientists, psychologists, and psychiatrists are not politically active or that they do not bring their politics into their work—many are and do. However, as part of the social sciences, these fields are at least conceived of as sciences.[7]

The comparatively activist orientation of Studies derives from its origins in the tumultuous social movements of the 1960s and 1970s (Ginsberg, 2025; Blakemore, 2023; Brown & Moorer, 2015). In practice, Studies disciplines often took root following protest campaigns led by student activists (Bates & Meraji, 2019; Lowery, 2009). In several cases, these campaigns included violence, intimidation, and other acts of domestic terrorism (Jaffa, 1989).

At such places, the continued presence of the Studies departments serves as a powerful reminder of how easily universities—proud bastions of the liberal tradition—succumb to political pressure. However, in all places where Studies departments are found, universities surrender credibility. The purpose of universities is to cultivate minds and pursue truth. To this end, universities purposefully challenge students with a wide variety of ideas (Newman, 1852; Kalven Committee, 1967). By contrast, the Studies indoctrinate students in narrow, ideologically pre-defined ways while demonizing their opponents and explicitly prioritizing the acquisition of power over truth (Bawer, 2023). It is one thing to engage with these disciplines but institutionalizing them amounts to endorsing them—a betrayal of the university’s mission.

But how does any of this implicate rigor? In practice, the Studies’ dual commitments to radical political activism and scholarship are in tension in at least two respects. First, these disciplines’ left-wing ideological commitments prevent comprehensive investigations of their own subjects. How, for example, can one meaningfully study African Americans and the African American experience without serious engaging with conservative black scholars or with non-leftist narratives of American history and society (McWhorter, 2009)? To take African Americans seriously as a subject of scholarly investigation, one must regard the black experience as something more than a case study in leftist politics.

Similarly, Women and Gender Studies’ contemporary feminist commitments render it implacably hostile to complimentary perspectives on the sexes and to men (Paglia, 2018). Given that recorded happiness has declined for American women for five straight decades during a period of ascendant feminism, in both theory and practice (e.g., mass female employment, decline of the nuclear family, deconstruction of heteronormativity and gender distinctions, etc.), perhaps the premise that women’s interests are synonymous with feminism deserves reconsideration (Stevenson & Wolfers, 2009; Blanchflower & Bryson, 2024; de Beauvoir, 1949; Millett, 2016; Butler 1990). This conversation seems relevant as women and girls’ rights, safety, and dignity are increasingly threatened by policies derived from recent developments by feminists in fields like Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies (Harrington, 2023).

The second way political activism undermines scholarship is by creating alternatives to traditional scholarly assessment. This concern most directly bears on the question of rigor. Consider, as an analogy, concerns raised by critics of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies in higher education. Substituting merit for rigor, DEI admission and promotion policies consider non-merit-based factors, such as an applicant’s race and sexuality, alongside merit-based considerations, such as scholastic aptitude. Defenders of DEI assert such policies merely add (in their view, important) evaluative criteria; however, giving any weight to non-merit factors necessarily dilutes the relative weight of merit factors. Likewise, prioritizing activism alongside subject mastery would tend to reduce subject mastery on average, in comparison to non-activist fields.

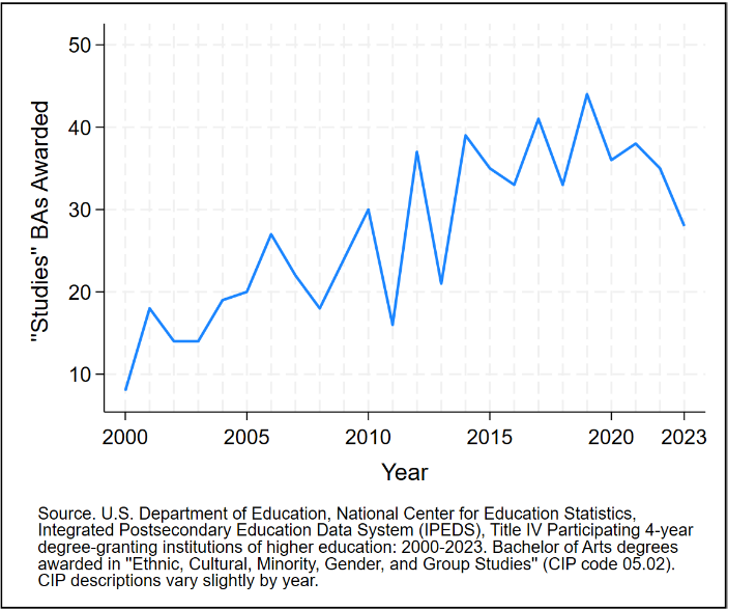

Methods

The author of this study investigated rigor at UT-Austin, a large public university that saw a 250% increase (albeit from 8 to 28) in bachelor’s degrees awarded in Studies departments since the year 2000 (see Figure 2). This was accomplished by consulting the UT Austin’s publicly available course grade distribution dataset, which lists student grades by department, course, and semester (The University of Texas at Austin: Institutional Reporting, Research, Information and Surveys, 2025).[8] Grades were obtained from the most recent 10 Fall and Spring semesters (2020–2024), excluding Summer session courses, which may not be comparable due to differences in student composition and pacing.

For comparison purposes, courses were selected from three broad categories: STEM, social science, and the Studies (see Appendix A for a full list of selected courses). English was also included as an additional point of reference. Degrees in STEM fields are highly valued in the labor market and command high returns on students’ educational investments (ROI). The same cannot be said of degrees in the Studies or the social sciences (excluding economics) (Cooper, 2021). The social sciences are therefore similar to the Studies both in terms of ROI and in the sense that both fields address social phenomena.[9] This comparison strategy allowed for the Studies to be examined alongside one generally similar and one generally dissimilar field.

In selecting courses to represent disciplines and fields, all “introductory” courses were initially included. These were defined as courses with no same-department prerequisite course requirements. Applying this standard helped to address selection bias concerns; however, several adjustments proved necessary. These included:

- “Macroeconomics” (304L), which requires students to have previously taken “microeconomics” (304k). In practice, both courses are foundational to the discipline and excluding macro leave micro as the sole introductory course with which to evaluate grading in the discipline. Macro was thus included alongside micro as an introductory economics course.

- Math, which presented a unique challenge in that every course had either a same-field prerequisite course requirement or a testing requirement. In this case, the no-same-field-prerequisite requirement was abandoned and the cap for “introductory” mathematics courses was set at “Differential and Integral Calculus.”

Additionally, lab courses were excluded from consideration, given that similar requirements are not widely shared across the disciplines considered. Finally, UT-Austin cross-lists Middle Eastern Studies 301L “Introduction to the Middle East: Adjustment and Change in Modern Times” with Government (political science) 303D. Rather than count this course twice, it was assigned to Middle Eastern Studies.

The process for evaluating rigor was straightforward. Two outcome measures were used: The percentage of “A” grades awarded, and GPA. Both measures were calculated separately at the department and field levels. For example, a department’s percentage of “A” grades awarded was calculated by dividing the total number of “A” grades awarded by the total number of grades awarded.[10] Department GPA was calculated by taking the mean of “A,” “B,” “C,” “D,” grades multiplied by their respective weights:

UT-Austin awards points to letter grades in the conventional way, as described in Table 1. UT-Austin does not provide official descriptions for grades, however. Conventionally, an “A” describes “excellent” work, a “B” describes “above average” work, a “C” describes “average” work, a “D” is “below average” work and an “F” constitutes failure.

Table 1. Grading Standards at the University of Texas at Austin

Letter |

Points |

Description* |

A |

4.0 |

“Outstanding” |

B |

3.0 |

“Above Average” |

C |

2.0 |

“Average” |

D |

1.0 |

“Below Average” |

F |

0 |

“Failure” |

Source. The University of Texas at Austin. (n.d.). Grades. Retrieved May 7, 2025, from https://onestop.utexas.edu/student-records/grades/ *Description attributed. |

||

As noted, a competitive environment presupposes that not every participant can be a “winner.” As measures of rigor, the percentage of “A” grades awarded and GPA provide leverage on whether UT-Austin is indeed, a competitive environment. Unfortunately, cross-department comparisons of rigor cannot account for noncomparabilities in student populations resulting from student self-selection into more or less rigorous disciplines. UT-Austin does not report data that would enable such a comparison—for example, standardized test scores by major field of study. Nonetheless, examining grading outcomes at the department level offers a valuable, if incomplete, glance at how seriously UT-Austin takes its responsibility to uphold high academic standards and the degree to which this responsibility is shared across its disciplines and fields of study.

Findings: How Rigorous are the Studies?

Percentage of “A” Grades Awarded

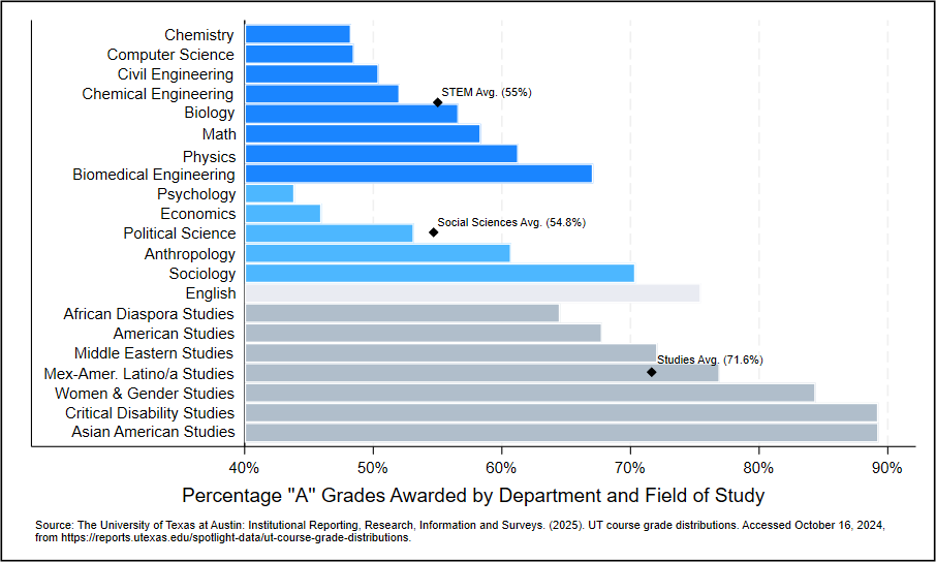

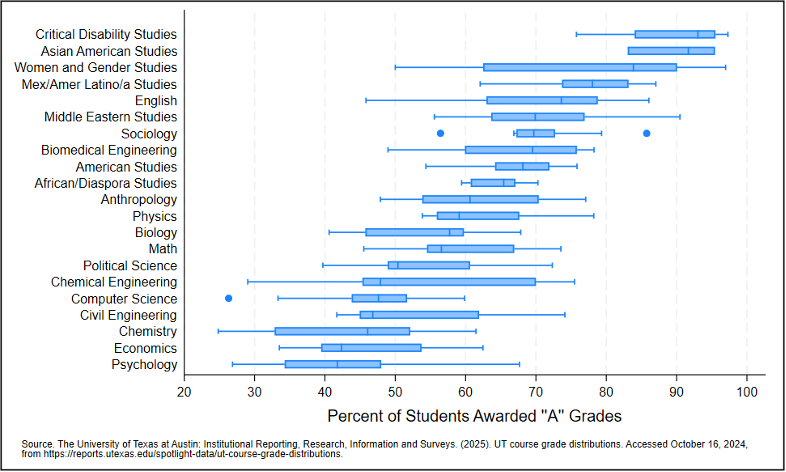

In line with expectations, the Studies were found to be systematically more generous (less rigorous) in awarding students “A” grades than the STEMs and social sciences. As displayed in Figure 3, across 10 semesters, Studies departments awarded “A” grades to between 64.5%–89.3% of students. By contrast, STEM and social science departments awarded “A” grades to 48.3%–75.5% and 43.9%–70.4% of students, respectively. English courses awarded “A” grades to 75.5% of students.

Looking across fields-as-a-whole, “A” grades were awarded to:

- 71.6% of students in Studies courses.

- 55% of students in STEM courses.

- 54.8% of students in social science courses.

Several findings stand out. First, the similarities between the STEMs and social sciences are striking, as are the dissimilarities between these fields and the Studies. The STEMs and social sciences award “A” grades at essentially identical rates. To be sure, awarding “A” grades to more than half of students is concerning. It is more difficult still to imagine how awarding “A” grades to more than 7 in 10 students can be justified. The shockingly high proportions of “A” grades awarded by the three “everybody wins” departments—Critical Disabilities Studies (89.3%), Asian American Studies (89.3%), and Women and Gender Studies (84.4%)—should raise concerns as to whether these departments meet even the minimum expected standards for rigor.[11]

Second, at least two social science departments appear to achieve reasonably standards of academic rigor, given the current, grade-inflated national environment (Rojstaczer, 2023). Indeed, Psychology (43.4%) and Economics (46%) are less generous than Chemistry (48.3%) or Computer Science (48.5%) when it comes to awarding “A” Grades. Excluding sociology, the social sciences are arguably the most rigorous of the three fields considered.

As noted, selection factors loom when comparing across departments and fields. Such factors may mitigate the apparent lack of rigor in Biomedical Engineering, for example (see Figure 3). Selection aside, and regardless of whether one accepts the premise that UT-Austin’s “soft” social sciences are more rigorous than its “hard” science STEMs, it would be difficult to characterize Psychology, Economics, and perhaps, Political Science as “un-rigorous,” based on these data. The point matters because the Studies are no less “soft” than the social sciences. If the relative “hardness” of a field is not the determinant of rigor, the manifest lack of rigor in the Studies demands an explanation.

Third, course-level data reveals the problem of inadequate rigor is not confined to the Studies. An incredible 90% or more of students were awarded “A” grades in nearly 1 in 5 (18.5%) Studies courses, but also in nearly 1 in 10 (9.7%) social science courses. The STEMs stand apart with only 2.5% of courses awarding “A” Grades to 90% or more of students.

Many of the worst offenders are found in small classes. For example, among the 13 courses to award every single student an “A” grade, class sizes ranged from 10–25. At the same time, lax grading in larger courses has a greater impact. This is particularly evident in the social sciences where “A” grades were awarded to:

- 92.4% of 158 students in Sociology 308S in Spring of 2020.

- 95.8% of 192 students in American Government 312L in Spring of 2020.

- 93% of 988 students in American Government 310L in Spring of 2024.[12]

Just as pennies add up to dollars, lax grading at the course level accumulates, producing absurd grade distributions at the department and ultimately, field levels. There appears to be ample room to ask more from UT-Austin students.

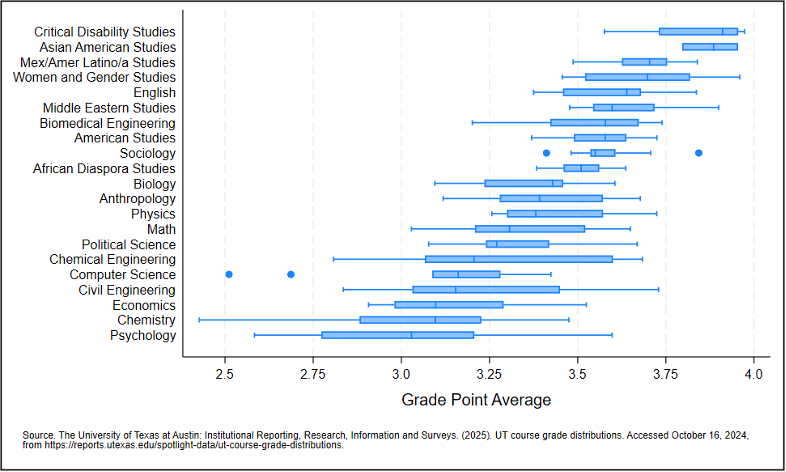

Grade Point Average

Turning to GPA, the data tells a similar story. Across the Studies departments, student GPA ranges from 3.5–3.86 with a field average of 3.6, roughly halfway between a “B” (above average) and an “A” (excellent). The average Studies student is evidently well above average.[13]

In the social sciences, GPAs range from 3.06–3.59 across departments with a field average of 3.31. In the STEMS, GPAs range from 3.12–3.53 across departments with a field average of 3.3. Translating to letter grades, the average social science and STEM student, like the average Studies student, falls within UT-Austin’s “B” range. The one third of a point GPA difference between these groups is substantial, however. This is equivalent to a grade difference at schools awarding points at the level of pluses and minuses (The University of Texas at San Antonio, n.d.). As with the percentage of “A” grades awarded, the STEMs and social sciences look similar to each other but different from the Studies. At the same time, the average social science/STEM student is still being graded as “above average”—a logical impossibility.

The similarities between the two measures of rigor are evident in Appendix B, where fields and departments are listed in ascending order according to percentages of “A” grades awarded. In several cases (emphasized in bold), listing fields and departments by GPA would alter the order slightly. However, in general, the differences between the two measures are minor. In no case do these differences complicate the broader findings regarding the Studies’ comparative lack of rigor.

Robustness

It is worth considering two potential challenges to these findings. First, examining measures of rigor across pooled time periods may obscure important semester-to-semester variation. Such variation would matter if, for example, rigor problems in the Studies are limited to only a few semesters.

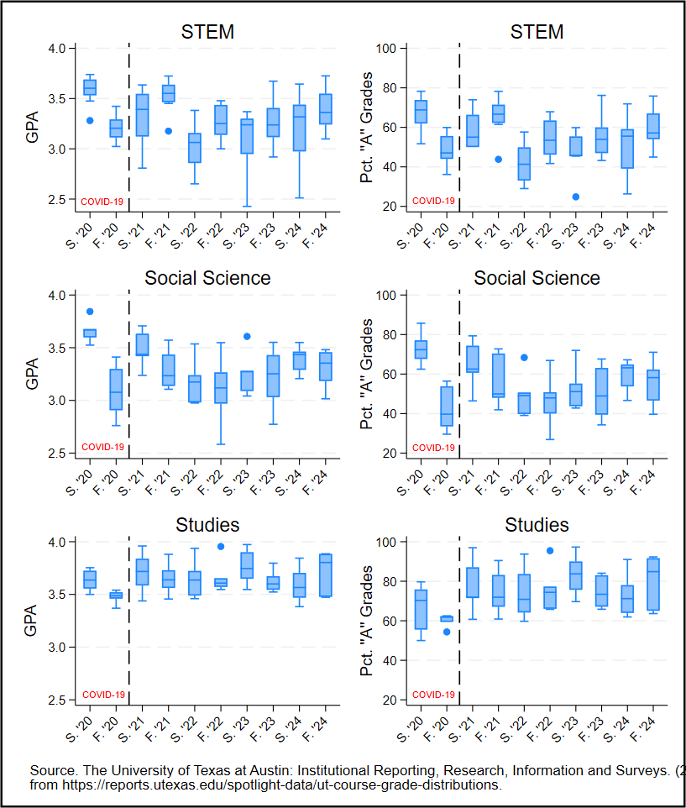

This concern can be addressed graphically using box plots: graphical depictions of key summary statistics. Box plots of department percentages of “A” grades awarded and GPA, are displayed in Figures 4 and 5, respectively. In both figures, the unit of observation is a rigor score for a given department, during a given semester.[14] The box represents the interquartile range or the middle 50% of the data. The vertical line in the middle of the box represents the median value. The “whiskers” extend to the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers (dots).

Box plots enable a quick visual comparison of categories, such as departments, that vary internally, such as by course and semester. For example, Figure 4 shows that, in both Critical Disabilities Studies and Asian American Studies, the median percentage of “A” grades awarded exceeds 90%. Furthermore, the middle half of the data is compressed relative to other departments, indicating less semester-to-semester variation.

Across both measures of rigor (Figures 4 and 5), substantial Studies departments interquartile range (box) variation is only evident in Women and Gender Studies. Unsurprisingly, greater variation is observed here in the percentage of “A” grades awarded than in GPA.[15] Overall, Figures 4 and 5 support the characterization of Studies departments as generally and consistently un-rigorous.

A second robustness question relates to COVID-19. The timespan of these data overlaps with the pandemic. This is unfortunate, given that the pandemic was a unique event known to have dramatically impacted nationwide education policies, including grading (Tillinghast et al., 2023). The evidence suggests rigor declined sharply during this period and has since only partially been restored to pre-pandemic levels (Kuperman et al., 2025; Fair, 2023).

In short, did COVID-19 impact rigor in some way that was specific to certain fields of study (e.g., the Studies) but not others? Much like the previous challenge, this question implicates whether this report’s findings are time/event specific, or alternatively, if there is broader phenomenon at play.

To address this question, box plots were again constructed, this time using departments as units of observation and plotting boxes for fields of study by semester. This approach depicts field-level, semester-to-semester changes in rigor (see Figure 6). The semesters most directly impacted by the pandemic (Fall and Spring of 2020) are separated by a red dotted line. Perhaps the most obvious takeaway from Figure 6 is the relatively high and, especially where GPA is concerned, compressed distribution of grading in the Studies. This consistency is remarkable, given that these fields also have smaller class sizes—a factor typically associated with higher variability.

Regarding the effects of COVID-19, the shift towards lax grading occurred in the social sciences and STEMs, rather than in the Studies. During the COVID-19 semesters, average GPAs were 0.1 points higher in the STEMS and in the social sciences, but 0.1 points lower in the Studies. More dramatically, average percentages of “A” grades awarded during COVID-19 were 3.9% and 3.4% higher respectively in the STEMS and social sciences but 13.4% lower in the Studies. Indeed, the Studies awarded fewer “A” grades than the social sciences in Spring of 2020 (66.3% vs. 73.1%).[16]

To summarize, COVID-19 did not uniquely compromise rigor in the Studies—on the contrary, but for COVID-19, the Studies would look even worse relatively to the other fields. It is unclear why this occurred and the cause could be idiosyncratic. For example, it may be that UT-Austin’s policy of allowing students to reclassify up to three Spring/Fall 2020 courses as “pass/fail” (i.e., removing these courses from grading averages) impacted some disciplines differently than others (Jaffee, 2020). Regardless, COVID-19 does not account for the paucity of rigor generally observed in the Studies.

Discussion and Recommendations

This report presents results from a cross-department investigation of rigor at UT-Austin. It finds Studies departments to be considerably less rigorous, on average, than the STEMs and social sciences. Grading in the Studies, whether measured by the percentage of "A" grades awarded or by GPA, is shockingly lax. It is also consistently lax: across departments, over time, and regardless of COVID-19, these disciplines are considerably less rigorous than their peers.

From the standpoint of universities, governing boards, and policymakers (higher education stakeholders), this laxness requires a response, particularly when considered alongside longstanding concerns regarding the Studies’ limited intellectual merits and activist posture. Grade inflation is a complicated and multifaceted challenge that affords few simple remedies. Eliminating low-value fields is one such remedy.

It is important to emphasize that eliminating departments in no way restricts speech or harms academic freedom. The presence or absence of specific, university-endorsed disciplines has no bearing on faculty members or students’ rights to express themselves or to research topics. The relevant consideration is whether universities desire to link their own credibility to uncredible disciplines—whether they will lie down with dogs and wake up with fleas, as the saying goes. The precedent is well-established: academic departments have been revamped or eliminated when judged by this standard and found to be wanting (Rufo, 2023).

Higher education stakeholders should ask themselves the following:

- Do the Studies, as university-endorsed departments, pursue truth and meaningfully advance the frontiers of knowledge?

- If not, are you comfortable compromising these fundamental commitments by continuing to host disciplines that pursue power over truth and activism over scholarship?

- What is the threshold for rigor below which a department or field is not permitted to fall?

With these questions in mind, this report offers the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Eliminate Studies Departments

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate departments classified as “Ethnic, Cultural Minority, and Gender Studies” by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate American Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies: “area Studies” disciplines that, in practice, function as (ethnic) Studies disciplines.

Recommendation 2: Reform or Eliminate Other Hyper-politicized Departments

- Higher education stakeholders should investigate the intellectual merits and grading rigor of other activist-oriented academic departments.

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate departments found to be lacking in either regard or found to be excessively politically or ideologically oriented. Alternatively, they should develop strategies to bring these departments in line with scholarly norms.

This report emphasizes rigor in the Studies; however, it has also uncovered concerning laxness in other disciplines. Sociology, English, and incredibly, Bio-medical Engineering are Studies-esque, in terms of rigor. Worse still, several courses in relatively rigorous departments (e.g., Political Science) award “A” grades to more than 9 in 10 students. Even the most rigorous departments award “A” grades to well over 40% of students. Higher education stakeholders should consider whether it is reasonable to rate 4 in 10 students as “excellent,” much less 5 in 10, 6 in 10, and so on. Arresting grade inflation will require reforms to address both low-value fields of study and general reforms aimed at restoring rigor across-the-board.

Reforms that fall in this latter category are more complicated.[17] One limitation of cross-department rigor comparisons is that student populations may be noncomparable. For example, if the scholastic aptitude of the average biomedical engineering student is markedly greater than the average student in another discipline, it may be unreasonable to expect comparable grades.[18] This problem is made even more complicated by the fact that scholastic aptitude can be disaggregated (e.g., math and writing) in ways that implicate programs of study—presumably math majors excel at math, for instance.

Universities collect and report students’ standardized test scores, such as Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and American College Testing (ACT) scores, to the NCES. Reporting these data at the course and department levels would help researchers to better disentangle rigor from scholastic aptitude. This, in turn, would allow for more precisely calibrated reforms. For example, a department GPA cap could be adjusted in response to changes in median student aptitude, as measured by SAT or ACT scores or perhaps their subcomponents (e.g., “mathematics” and “evidence-based reading and writing”).

Absent better data, higher education stakeholders should again, pursue simple and intuitive “low hanging fruit” reforms. If students can’t all be “winners,” and if an “A” grade represents “excellent” work, awarding “A” grades to more than 40% of students seems absurd. Higher education stakeholders should additionally work to develop comprehensive and more precisely calibrated reforms. Given that low and declining rigor constitutes a collective action problem, these efforts will be most successful if many universities participate in a common effort.[19] The Department of Education, Congress, or both can help these efforts by ensuring standardized test scores are available by major field at the degree program level.

Recommendation 3: Constrain Grade Inflation

- Higher education stakeholders should impose an initial across-the-board cap of 40% on the percentage of “A” grades awarded at the class and department levels.

- Universities should adjust these caps based on average student quality, as measured by average student standardized test scores.

- Higher education stakeholders should work cooperatively at the regional or national level to develop and implement reforms to improve grading rigor and to constrain grade inflation

Recommendation 4: Improve Data Reporting

- The Department of Education should utilize its data reporting authorities to require Title IV participating institutions to collect and report average student standardized test scores (SAT and ACT) at the course and department levels (Schorr, 2025).

- Congress should codify these requirements in the Higher Education Act.

[1] Maintaining a fixed standard of rigor will not restrain grade inflation if the quality of students increases.

[2] The term is most often used in references to ethnic rather than area studies. For example, East Asian Studies addresses “the history, society, politics, culture, and economics of one or more of the peoples of East Asia, defined as including China, Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Taiwan, Tibet, related borderlands and island groups…” (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.-a). This is not a “Studies” discipline, as defined here or as commonly understood (e.g., Bawer 2023). In other cases, such as Middle Eastern Studies and American Studies, the radical ideological and activist commitments of these (technically, area studies) disciplines justifies their inclusion among the Studies (Kramer, 2001; Fluck & Claviez, 2003).

[3] The only reported course to award a higher percentage of Yale students “A” Grades than “Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies” was “History of Science, History of Medicine” (Fair, 2023).

[4] Notwithstanding the absence of “Studies” in the title, Yale College’s “Ethnicity, Race, and Migration” is a “Studies” department course (Yale University, n.d.).

[5] The “Grievance Studies Affair,” an academic hoax perpetrated by James Lindsay, Peter Boghossian, and Helen Pluckrose, was a highly publicized but decidedly nontraditional investigation of rigor in the Studies and in related fields (Lindsay et al., 2018).

[6] The U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) classifies fields of study in higher education using “classification of instructional program (CIP) codes. The category “05.02: Ethnic, Cultural, Minority, and Group Studies” largely encompasses “the Studies,” as traditionally understood; however, several disciplines listed under “05.01: Area Studies” (e.g., American Studies) could also be included among “the Studies” (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.-b). IPEDS does not record class enrollment by department. Bachelor’s degrees awarded by department are thus used as a proxy for Studies enrollment.

[7] Anthropology, a field that featured zero registered Republicans in a recent survey of 8,688 tenure-track Ph.D.-holding professors (Langbert, 2018), has adopted a Studies-like posture towards the scholarship vs. activism divide. The American Anthropological Association (AAA) formally embraces cultural relativism and asserts that “research and engagement” in its field must “contribute to decolonization and help redress histories of oppression and exploitation (AAA, 2020).

[8] Texas A&M likewise reports grades at the class and semester level (Texas A&M University Office of the Registrar, n.d.). Similar data exists for the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Purdue University by non-university sources (Thomas, 2024; "Boiler Grades," n.d.).

[9] Cooper (2021) examines ROI from 30,000 bachelor's degree programs by comparing post-graduate earnings to college tuition and living expenses. He finds students’ risks of earning negative ROIs are high in several fields, including "political science and other social science" (53%) and "English, Liberal Arts and Humanities" (57%), a category that would presumably include the Studies. By contrast, 0% of Engineering students and only 11% of "mathematics and statistics" and "economics" students earned negative ROIs.

[10] Alternatively, one could calculate the percentage of “A” grades awarded at the course level and then assign the mean of these scores to the respective departments; however, this approach overweights small classes by assigning equal weight to courses rather than to students.

[11] Asian American Studies and Critical Disability Studies were offered three and four semesters, respectively during the 10-semester period spanning from 2020-2024.

[12] In line with the consumer demand thesis for grade inflation, the professors who taught these three courses appear to be popular. According to reviews posted to the website RateMyProfessor.com, the trio received high average marks for quality and low average marks for difficulty, overall and immediately following the semesters in question (see Appendix C, Rate My Professors, n.d.; Rate My Professors, 2023). One student described American Government 310L the following way: “Greatest of all time. Easiest class I’ve taken, if you just need your government credit there is nothing easier than this. There is just weekly quizzes and two tests, with topics you should be able to ace and already know from high school” (Rate My Professors, n.d.).

[13] As a point of reference, UT-San Antonio assigns point values to plus and minus grades and descriptors to all grades. It defines a “B+” as covering GPAs ranging from 3.33–3.67 and describes this grade/range as “well above average” (The University of Texas at San Antonio, n.d.).

[14] This approach is different than the one depicted in Figure 3, where estimates are pooled across semesters for each department.

[15] GPA ranges from zero-to-four with decimals, allowing for a far greater range of values than the percentage of “A” grades awarded, which is measured from 0-100. In practical terms, it would be possible for a sizable decrease in the percentage of “A” grades awarded from a prior semester to only minimally impact the average GPA of a given course if, for example, that course experienced a (partially) compensating increase in the percentage of students awarded “B+” grades.

[16] In the subsequent (Fall 2020) semester, each field—but especially the social sciences—became dramatically more rigorous.

[17] This report does not address broader strategies for combating grade inflation, though (see Chowdhury, 2018; Butcher et al., 2014; and Nagle, 1998).

[18] For example, SAT scores vary among high school students by major of interest. In 2024, the mean scores for “Biological and Biomedical Sciences” students exceeded mean scores for “Area, Ethnic, Cultural, and Gender Studies” by 105 points (1145 to 1050; “SAT Suite of Assessments Annual Report,” 2024).

[19] Collective action problems involve individual disincentives to joint action for mutual benefit (Dowding, n.d.). For example, restraining grade inflation is broadly beneficial; however, lax graders benefit from favorable student assessments (Rojstaczer, 2023).

References