Effective Implementation of the Elementary and Secondary Schools Act’s “Persistently Dangerous” Schools Designation

Key Takeaways

New Trump-McMahon Department of Education guidance directs states to revisit policies concerning transfer opportunities for students attending “persistently dangerous” schools.

These authorities are far-reaching. Nationally, approximately 4 in 5 public school students could be eligible for public school choice under a straightforward application of the Unsafe School Choice option.

States should capitalize on the opportunities provided to them by the Department of Education’s new guidance to promote school choice opportunities for K-12 public school students.

In designating schools as persistently dangerous, a key consideration should be the presence or absence of a full-time school resource officer.

The Unsafe School Choice Option

The Department of Education has released new guidance aimed at bolstering school choice opportunities for students attending unsafe K-12 public schools (Sanon, 2025). The Department’s letter references a little-known provision of the Elementary and Secondary Schools Act (ESSA) that requires states to provide public school choice to: 1) individual students who suffer violent criminal offenses on school grounds, and—crucially—to 2) students attending schools designated as “persistently dangerous” (PD) “by the State in consultation with a representative sample of local educational agencies…” (20 U.S.C. 7912).

Noting that this provision has not been broadly implemented, the Department recommends states adopt full open enrollment policies, and establish clear “protocols for defining and identifying persistently dangerous schools” and for notifying “parents whose children attend unsafe schools or have been the victim of a violent criminal offense” (Sanon, 2025).

The Department further encourages states to adopt a broad interpretation of the ESSA’s Unsafe School Choice Option. For example, regarding the persistence of danger on school grounds, the Department encourages states to consider incidents occurring within a single, rather than multiple, year(s). Regarding danger, the Department encourages states to consider such things as “persistently poor academic performance” alongside considerations, including:

- “Incidents or fear of physical harm.”

- “Whether weapons have been seized on campus.”

- “Whether the school has an intimidating or threatening environment.”

- “Any other conditions or outcomes that the State finds make a school persistently dangerous.”

- “School[s] without a School Resource Officer (SRO)” (Sanon, 2025).

Defining “Persistently Dangerous” Schools

State policymakers should anticipate that their efforts to comply with the Department’s new guidance may be scrutinized. Consequently, the criteria by which states designate schools as PD must be chosen with an eye towards survivability as well as impact.

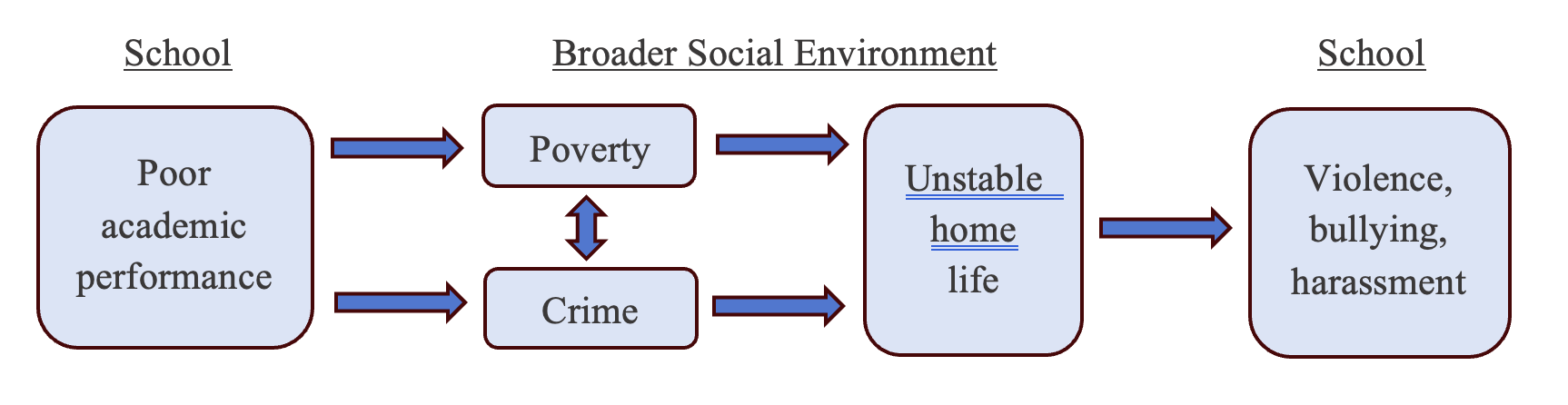

In terms of the Department’s suggested criteria, “persistently poor academic performance,” well-established associations exist between poor academic performance and unsafe schools. For example, poor academic performance is known to increase risks of crime and incarceration. See the facts below:

- Third grade reading levels predict adult incarceration rates (Kameen et al., 2012).

- One in 10 male high school dropouts will be incarcerated in adult or juvenile detention facilities over the course of their lifetimes (Dillon, 2009).

- Incarceration rates are 63 times higher for high school dropouts than for college graduates (Sum et al., 2009).

- Prison education programs have been shown to reduce recidivism by 7-15%, suggesting an association between education, employment, and crime (Schuster & Stickle, 2023).

The relationship may be depicted as follows:

This is a multistep relationship involving broader community factors. By contrast, other criteria suggested by the Department (e.g., “incidents or fear of physical harm” and “whether weapons have been seized on campus”) themselves constitute dangerous school conditions. The tighter connection of these measures to the ESSA’s Unsafe Schools provision may render them more durable under legal scrutiny.

Among these criteria, the absence of a full-time campus SRO deserves special attention. SROs play a vital, lifesaving role in K-12 education by protecting students, faculty, and staff during school shootings and other mass-casualty events. A simple way to understand the importance of SROs is to consider the likely response time for an off-campus police officer—meaning, the time to drive to the campus from wherever the officer is dispatched—in comparison to the time required for an on-campus police officer (SRO) to respond to a notification from school staff or to hearing gunshots himself. Simply put, the longer it takes for an armed police officer to engage the shooter, the greater the likely number of shooting victims.

This point was dramatically illustrated at two San Diego high schools in 2001. On March 5, 2001, a mass shooter killed two students and injured 13 more at Santana High School, a school that lacked a dedicated SRO (Ojeda, 2021). Two weeks later, a copycat shooting at Granite Hills High School, a school with a dedicated SRO, resulted in zero fatalities (ABC News, 2001). In both cases, the police response was swift. The Santana shooting lasted less than six minutes (CNN, 2001). At Granite Hills, where the police response was instant, the shooting lasted less than two minutes (Bowman, 2001).

Estimating the Impact of Persistently Dangerous Designation Criteria

Utilizing publicly available data provided by the Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR), it is possible to estimate the number of transfer-eligible students attending K-12 public schools using a variety of PD designation criteria (OCR, 2025a; OCR, 2025b). These data do not encompass all potential PD criteria—for example, illegal drug-related incidents and literacy rates are not included—however, they include many of the most obvious measures state policymakers could seek to use, such as:

- Homicide incidents

- Shootings

- Incidents involving the possession of firearms or explosives

- One or more full-time SROs

- Rape incidents

- Physical attacks, fights, and robbery, both with and without weapons

- Sexual battery incidents (other than rape)

The OCR data additionally include accusations of harassment and bullying related to race, color, national origin; religion; sex; sexual orientation; and disability status.

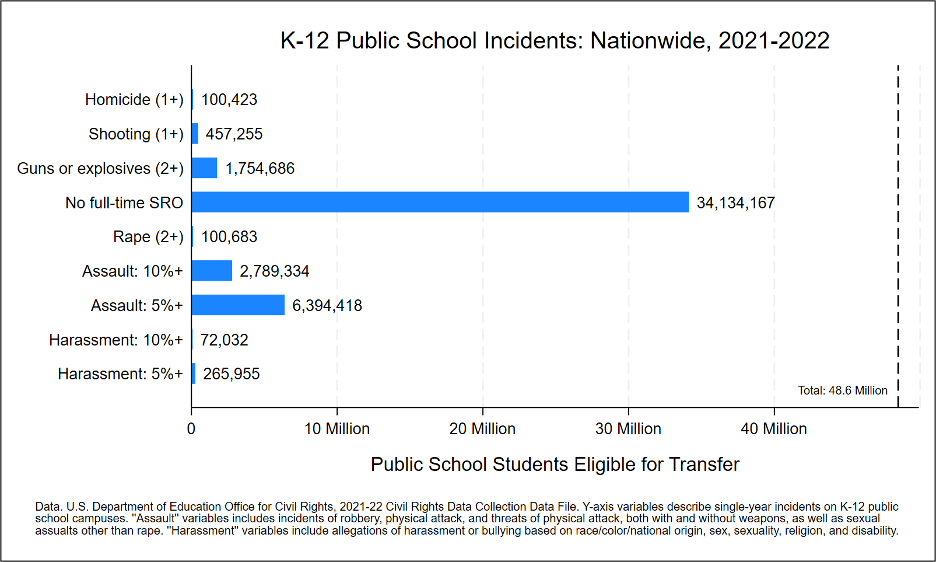

Figure 1 depicts the number of K-12 public school students who could be made eligible for transfer based on the proposed individual PD criteria.[1]

For the first two criteria (homicide and school shootings), the data are coded as “yes”/“no” rather than by the number of incidents. This convention makes it impossible to identify schools where more than one such incident occurred; however, these incidents are sufficiently extreme as to warrant their inclusion.

The next criterion captures repeated (meaning two or more) incidents involving firearms or explosive devices on school grounds. This is followed by the absence of a full-time SRO, and repeated instances of rape. The subsequent “assault” and “harassment” measures are derived from dividing the combined totals for the relevant incidents by a school’s total student population. This means that, for example, a school designated as “Assault 10% +” had repeated instances of physical attacks, fights, and robbery (with and without weapons) amounting to at least 10 per 100 students over the course of the school year.

Figure 1 presents nationwide estimates. As such, it presents the unlikely scenario wherein all states have enacted identical regulations. Despite this limitation, Figure 1 demonstrates the relative impact of the primary criteria by which states would be likely to define a school as PD, in line with the Department’s new guidance.

Without question, the most impactful criterion for PD designation is the absence of a full-time SRO. This single criterion covers more than 80% of schools and over 34.1 million students, nationally. It should be noted that approximately 13% of schools (6.3 million students) employ part-time

SROs (OCR, 2025b). A part-time SRO is better than no SRO; however, it is clearly insufficient. For example, if an SRO is stationed at a school on Mondays through Wednesdays, that school’s students, faculty, and staff are vulnerable to an increased risk of death from a mass shooting event every single Thursday and Friday. This seems like the very definition of persistent danger.

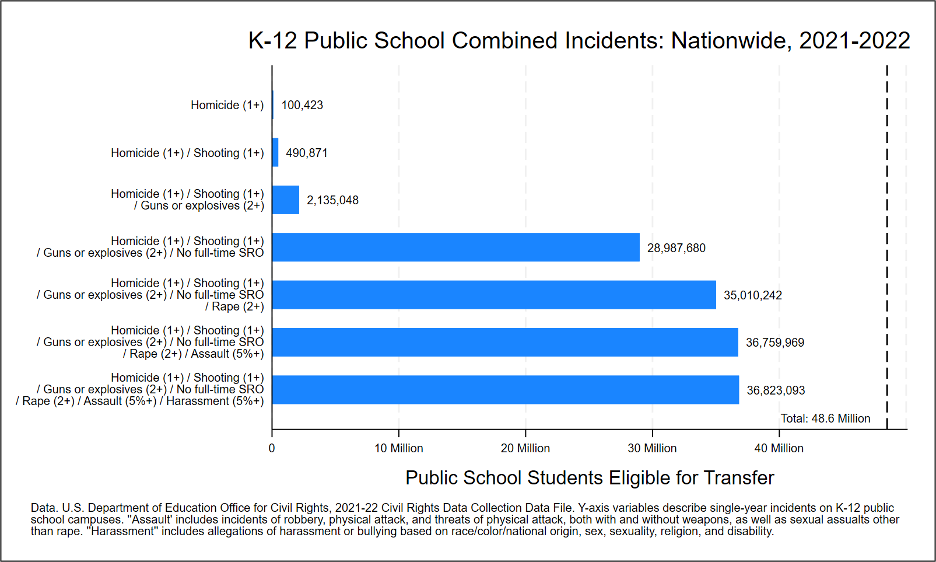

The most useful way to think about PD criteria is to consider their combined impact on students’ transfer eligibility. Given that few states would be likely to assign PD status based on less but not more dangerous criteria (e.g., assault but not homicide), it makes sense to “walk out” estimates, proceeding from most to least severe PD designation criteria, as depicted in Figure 2. Five percent estimates for assault and harassment variables are used here for simplicity. It is difficult to imagine states omitting any of these criteria, except perhaps harassment. Yet, even here, it can be expected that many state leaders will view harassment and bullying directed at children based on race, sex, religion, sexuality, and disability status as contributing to unsafe school environments.

Conclusion

The Department’s newly released guidance addressing the ESSA’s Unsafe School Choice Option is a game changer for choice and safety in public schools. As described in this issue brief, a straightforward application of the Department’s guidance would radically expand transfer eligibility for K-12 public school students. The resulting system of near-universal public school choice would greatly improve upon the current model wherein students are denied meaningful opportunities to escape from dangerous and otherwise failing schools. States have a moral obligation to their students to take advantage of this opportunity. Every American student should be free to develop their minds in an environment free of persistent danger.

This issue brief has focused particular attention on the importance of full-time campus SROs. As depicted in Figure 1, this is the most impactful criteria for PD designation, by far, in terms of transfer eligibility. In addition to providing greater choice opportunities for public school students, linking PD designation to full-time SRO presence will encourage more schools to make this critical investment to increase public safety in schools.

Unlike transfer eligibility, it is difficult to definitively state how expanding SRO presence in K-12 public schools could benefit students, in terms of safety. This is because statistics struggle to capture events that did not occur, such as banks not robbed, homes not broken into, and mass shootings not committed because would-be assailants reasonably judged their prospects for success to be diminished by the presence of an armed opponent. Yet it stands to reason that a substantial expansion in full-time SROs could significantly reduce school incidents and save numerous innocent lives. All the more reason for states to take advantage of the Department of Education’s new guidance.

[1] For example, the variable “Homicide (1+)” in Figure 1 displays the total number of students enrolled in a K-12 public school in which one or more homicides occurred during the 2021-2022 academic year. Figure 2. progressively combines these estimates (e.g., “Homicide (1+),” “Shooting (1+ ),” “Guns or explosives (2+)”…) to estimate the cumulative impact of adding PD criteria. Enrollment totals do not double count students enrolled in schools with multiple PD criteria—e.g., students attending a school with one or more homicides and one or more shooting are counted one time.

Works Cited