“Low-hanging Fruit” Solutions for Grade Inflation

Key Takeaways

Grade inflation reduces student achievement and diminishes the value of grades as records of academic quality.

Higher education stakeholders can enact simple policy remedies including capping the proportion of “A” grades awarded at the course level and eliminating low-value-low-rigor disciplines.

Congress and the Department of Education can help higher education stakeholders to combat grade inflation by requiring Title IV institutions to report average student standardized test scores at the course and department levels.

AFPI Tackles Grade Inflation

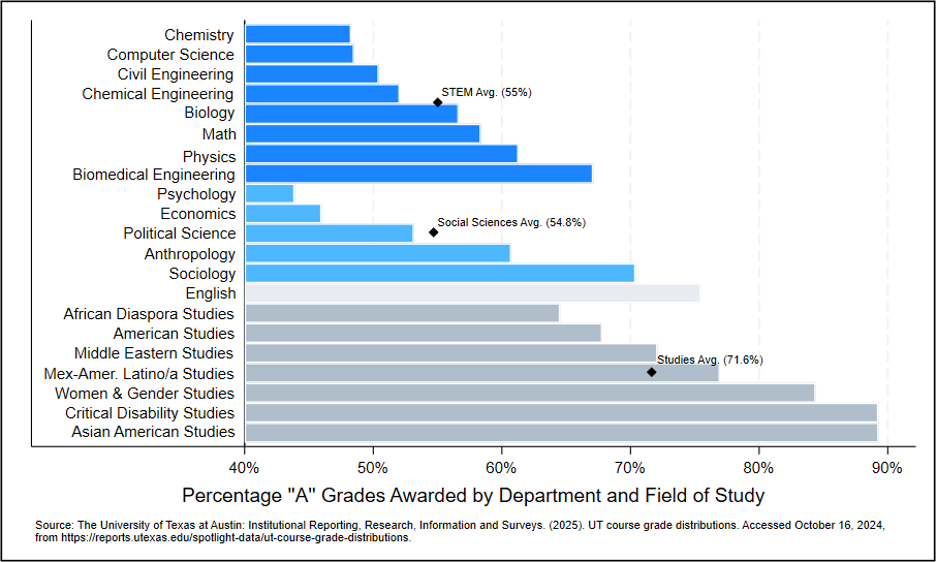

The America First Policy Institute has released a new report proposing simple solutions to grade inflation, the tendency for average grades to rise overtime (Schorr, 2025). Drawing on 10 semesters of data obtained from 21 disciplines at the University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin), the report compares grading rigor across three fields of study: science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM); the social sciences; and “the Studies.”

Recent decades have seen steady increases in the proportions of “A” grades awarded and GPAs across institutions of higher education. The main culprit appears to be college graders’ willingness to accede to “consumer demand” from their students (Rojstaczer, 2023). In a nutshell: lax grading results in happy students who, in turn, write favorable teaching assessments of graders (professors and graduate students).

Unfortunately, lax grading is not a “victimless crime.” Grades are meant to provide a record of student quality—subject matter mastery, diligence, and skill—for prospective employers and graduate admissions officers. Lax grading results in “students who do exceptional work [being] lumped together with those who have merely done good work, and in some cases with those who have done merely adequate work” (Mayhew, 1993). This reduction in accountability may help to explain the association between lax grading and reduced studying and learning by students (Babcock & Marks, 2010; Arum & Roksa, 2011).

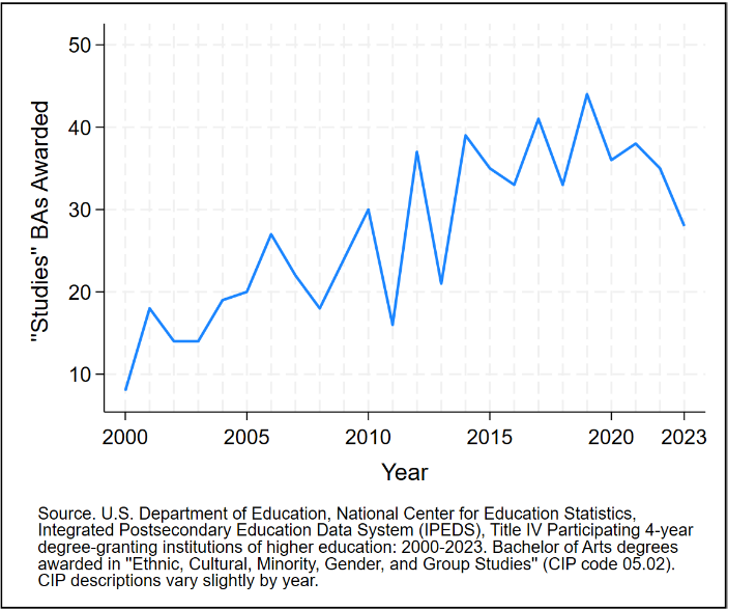

Alongside the “consumer demand” problem, student self-selection into less rigorous disciplines contributes to reduce average grading rigor, over time (Hernandez-Julian & Looney, 2016). In this context, the growth of a relatively new collection of disciplines known as “the Studies” demands investigation. The term “the Studies” refers to “ethnic studies” disciplines, such as African American Studies and Latino/a/x Studies, but also to fields like Women and Gender Studies, and Critical Disability Studies. Some “area studies” disciplines, such as Middle Eastern Studies and American Studies, may also be included in this category.

The Studies have long faced criticism for their limited intellectual merits and for prioritizing political and social activism over scholastic rigor (Ginsberg, 2025; Paglia, 2018).[1] The two concerns are related insofar as the Studies’ activist commitments preclude comprehensive investigations of their topics (McWhorter, 2009; Paglia, 2018). These same commitments could also detract from rigorous grading by introducing competing evaluative criteria (political activism) alongside traditional, scholarly assessments. In this context, the Studies steady growth overtime, as displayed in Figure 1, could contribute to grade inflation. Anecdotal cases of comically lax grading in Studies disciplines further suggests this possibility merits investigation (Fair, 2023).

Report Findings

In comparing rigor across disciplines and fields at UT-Austin, the Studies stand apart with a remarkable 7-in-10 (72%) students receiving “A” grades from 2000–2025. By contrast, just over half (55%) of STEM and social science students received “A” grades during the same period (see Figure 2). With an average GPA of 3.6, the Studies again look far less rigorous than the STEMs and social sciences, both of which averaged GPAs of 3.3.

Grading in UT-Austin’s Studies disciplines is scandalously lax. Indeed, several disciplines, including Critical Disabilities Studies (89% “A”), Asian-American Studies (89% “A”), and Women and Gender Studies (84% “A”), are on the threshold of awarding every student

an “A” grade. One might ask why a university would choose to host disciplines that are neither scholarly nor rigorous. Texas higher education stakeholders, including university leaders, governing boards, and policymakers, should consider what, if any goal is served by compromising across-the-board rigor by hosting low-value-low-rigor disciplines.

The STEMs and social sciences are both comparatively rigorous; however, awarding “A” grades to over half of students seems excessive. Conventionally, an “A” describes “excellent” work, a “B” describes “above average” work, and a “C” describes “average” work. By this standard, the most common (i.e., average) grade should be a “C.” If this adjustment seems either too extreme given the larger (grade-inflated) national landscape, modest reforms such as capping the number of “A” grades awarded at the course and department levels could offer a modicum of desperately needed grading discipline.

To this end, it may be helpful to allow course and department grade caps to fluctuate based on the scholastic aptitude of their average student. This adjustment could help to mitigate any post-grade cap migration of high-quality students from high-to-low rigor fields in search of higher grades.

Recommendations

With these findings in mind, AFPI recommends the following:

1. Eliminate Studies Departments

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate departments classified as “Ethnic, Cultural Minority, and Gender Studies” by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate American Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies: “area studies” disciplines that, in practice, function as (ethnic) Studies disciplines.

2. Reform or Eliminate Other Hyper-politicized Departments

- Higher education stakeholders should investigate the intellectual merits of and grading rigor of other activist-oriented academic departments.

- Higher education stakeholders should eliminate departments found to be lacking in either regard or found to be excessively politically or ideologically oriented. Alternatively, they should develop strategies to bring these departments in line with scholarly norms.

3. Improve Data Reporting

- The Department of Education should utilize its data reporting authorities to require Title IV participating institutions to collect and report average student standardized test scores (SAT & ACT) at the course and department levels (Schorr, 2025b).

- Congress should codify these requirements in the Higher Education Act.

4. Constrain Grade Inflation

- Higher education stakeholders should impose an initial across-the-board cap of 40% on the percentage of “A” grades awarded at the class and department levels.

- Universities should adjust these caps based on average student quality, as measured by average student standardized test scores.

- Higher education stakeholders should work cooperatively at the regional or national level to develop and implement reforms to improve grading rigor and to constrain grade inflation.[2]

[1] “Area studies” are distinct from “ethnic studies,” conceptually and in official university data (see: National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). However, given the radicalism and political activism characteristically found in Middle Eastern Studies and American Studies—both technically “area studies” disciplines—these are included among “the Studies” in this report (Kramer, 2001; Fluck & Claviez, 2003).

[2] For examples see: Chowdhury (2018), Butcher et al., (2014), and Nagle (1998).

References