Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights: A State-Level Solution that Slams the Brakes on Government Growth

Key Takeaways

An explosion in government spending at the federal and state levels that began during COVID-19 has persisted long after the crisis ended.

This ongoing spending binge has failed to deliver tangible benefits, instead fueling decades-high inflation that erodes the value of workers’ paychecks.

Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights offers the toughest state protections to date from higher taxes and spending. Other states ought to learn from Colorado’s experience by implementing their own “Next Generation” Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights that puts the brakes on excess government growth

Introduction

While policy discussions about the growth of government spending in response to the COVID-19 crisis have largely centered around federal initiatives, projected state and local budget shortfalls throughout the country have drawn attention to government growth at the state and local levels since 2020. Proposals to address these shortfalls through increased taxes and bonds to avoid cuts and “preserve services” have taxpayers especially concerned that the burden they bear for the government’s growth will only worsen. In places with balanced budget rules prohibit government borrowing, the discussion has often focused on increasing taxes to close the shortfall instead of rolling back spending to normal pre-COVID levels.

Indeed, the growth of state and local government revenues and expenditures has been staggering. In less than one year, beginning in July 2020, the federal government made direct transfers to state and local governments totaling some $512 billion, ostensibly to fund services in response to the pandemic. The sheer size of this transfer is hard to overstate: No state, territory, or tribal nation received less than $1.25 billion from the CARES Act. At the beginning of the pandemic, it was unclear what the fiscal effect on states and municipalities would be, and providing narrowly tailored, COVID-related federal aid to states and localities had some merit. Yet long after these effects from COVID-19 were largely mitigated, the federal government earmarked more than $362 billion in March 2021 for states and localities through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). This money had far fewer guardrails on how it could be used. The funds ARPA transferred to states continued to cover a broad range of allowable expenditures incurred through 2024. Thus, the original COVID justification for federal assistance has given way to a generalized glut in government spending and new programs unrelated to the public health emergency.

The infusions of federal funds are waning and many state and local leaders have turned to proposed tax increases and other revenue-generating measures to sustain government growth. In response to these taxpayer concerns, pro-government politicians have aggressively tried to stop affronts to their power to continue to grow the government. A recent example is the California Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in June, which kept citizens from voting on The Taxpayer Protection and Government Accountability Act of 2024, a ballot initiative that would have required, among other things, that new state and local taxes be subject to a two-thirds approval of voters. The court agreed with the state legislator who filed the lawsuit that a ballot initiative could not make these revisions to the state constitution (California v. Weber, 2024). Observers noted that the ruling was “a victory not only for Newsom and legislative leaders…[but also] the Democratic Party’s most powerful political allies in public employee unions, which were prepared to spend tens of millions of dollars to defeat it” (Walters, 2024).

Arguably, state and local governments, which manage schools, infrastructure, and public safety, among other programs, affect residents’ day-to-day lives more closely than the federal government. Indeed, as state governments grow their footprints, these government expenses multiply and further strain taxpayers as more bond assessments are added to property tax bills and increasing sales taxes take up larger line items on their receipts. The dramatic increase in government spending seen in the wake of COVID-19 is unsustainable.

Yet what of the taxpayer protections already in place that are aimed at preventing dramatic increases in government? The most common of these protections are tax and expenditure limits (TELs), which, simply put, are “restrict[ions on] the growth of government revenues or spending by either capping them at fixed-dollar amounts or limiting their growth rate to match increases in population, inflation, personal income, or some combination of those factors” (Tax Policy Center, 2024). In fact, more than 30 states have TELs, with some stronger than others. Yet two states with noted TELs, California and Missouri, have still been unable to stem the growth of state government and rising taxes despite what began as effective TELs.

Proposition 13 is California’s main barrier to tax increases and government growth; it limits property tax increases and reassessments while also requiring a supermajority vote of the legislature for all state tax increases. Despite the law’s success and popularity, the state has progressively weakened it through the ballot box and ongoing manipulations by lawmakers in the more than 45 years since its enactment. Missouri’s Hancock Amendment is a voter-approved constitutional amendment that prohibits state revenue from exceeding the ratio of personal income to state revenue in 1981, the year the amendment was enacted. Revenue beyond this ceiling must be refunded to taxpayers. Yet experts have deemed the amendment “obsolete and ineffective,” as tweaks to this protection have rendered it inadequate to restrain the development of Missouri’s tax and spending apparatus since the amendment’s approval in 1980 (Tsapelas, 2024).

One protection against tax increases, however, has stood out as a gold standard for containing government growth and restoring freedom to taxpayers. Colorado’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights (TABOR), which voters passed by initiative in 1992, has a decades-long track record of success in its stated goals to “limit the amount of revenue the state can retain and spend…[and] absent voter approval, [for] excess revenue to be refunded to taxpayers” (Colorado Department of Revenue, n.d.-a). For more than three decades, TABOR has limited growth in taxpayer-funded spending by the state compared to the previous year’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) in its largest metropolitan statistical area, plus projections for population growth for the coming year. Revenue more than this limit must be refunded to taxpayers from the state’s general fund. Other protections include requiring voter approval for tax increases and for the lifting of the TABOR revenue limits (Ramey, 2022).

While Colorado’s TABOR has proven a resilient and strong TEL despite shifting political winds in the state and has done an admirable job protecting Colorado taxpayers from an increasing burden of government, it, too, has its shortcomings. More broadly, this report argues that updated and even stronger protections are needed to protect citizens from their state governments’ voracious appetites for more taxpayer money. At present, many states have far weaker protections—if any at all—than what Coloradans enjoy. This report provides a path forward for states across the country to implement even more robust protections—"Next Generation” TABOR—that proactively stop politicians from finding ever more creative ways to expand the size, scope, and burden of government without taxpayers having any direct say.

The Attempted Permanent Expansion of Government After COVID

As noted in the introduction, the federal government has directly transferred more than $885 billion to state and local governments in response to COVID-19. Some 60 percent of these transfers were appropriated in 2021 after state revenues had stabilized, and it was clear these state revenues and rainy-day funds would cover budget shortfalls. In fact, state and local receipts for the fourth quarter of 2020 were 6 percent higher than receipts for the fourth quarter of 2019, a fact known when ARPA was passed in March 2021 (CRFB, 2021). While states could have acted responsibly with these funds, using them to reduce debt or augment their rainy-day funds without adding to their total spending, the trend instead was for states to expand their government sectors and create or expand state programs. These states now face a fiscal reckoning.

This growth in government was intentional and even cynically pursued by some in power. As Congress debated COVID-19 relief initiatives, a faction of congressional leaders with a preference for expanding government commented that these bills presented “a tremendous opportunity to restructure things to fit our vision” and proceeded to add appropriations for special interests in the succeeding relief packages that were irrelevant to addressing the pandemic (Lillis & Wong, 2020). It is no surprise, then, that state and local leaders in high-tax jurisdictions sought to spend these funds to grow their governments and create future funding commitments. States and major cities indicate this trend.

Illinois is a key example that typifies the behavior of many high-tax state jurisdictions, especially when not limited by a TEL (Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, 2024). The state received more than $8.1 billion in direct funds from the ARPA and spent it indiscriminately. In fact, a 2019 forecast predicted a $3 billion shortfall for fiscal year 2023, which turned into a $1.7 billion surplus. Flush with ARPA funds, the state enjoyed three years of state budget surpluses. Yet by 2024, the state faced a nearly $900 million deficit for its $53 billion budget and about $5 billion in projected deficits through 2028. Experts attribute these deficits to structural issues, most notably the state’s public pension liabilities and millions spent responding to the influx of migrants. For reference, Illinois saw about 35,000 migrants arrive in 2023 and spent lavishly on its “ongoing efforts in moving 9,000 migrants from temporary shelter to more stable housing” (Shepherd & Kaufmann, 2024).

During the years Illinois enjoyed surpluses, it wisely used some of that money to increase its rainy-day fund, reduce its lingering bond debt from the Great Recession, and repay its Unemployment Trust Fund debt to the federal government. Yet it also vastly expanded its public sector programs with its surpluses and ARPA funds. These expenditures eclipsed debt reduction and other nominal structural reforms (Pritzker, 2024). These imprudent expenditures virtually guaranteed that Illinois would face the same structural deficits again. For example, by the governor’s own admission, although it has the largest balance in its history, “the Illinois rainy-day fund is still among the smallest” state rainy-day funds (Pritzker, 2022). More importantly, the state missed an opportunity to reduce taxes and the general burden of government and to stimulate economic growth to increase workers’ paychecks. Had the state not expanded its financial commitments, it may even have avoided the budget deficits it now confronts, and the state would have been able to enact or consider greater tax cuts now and into the future. Instead, the state used $60 million in COVID relief funds to create new youth programs, $1 billion to “stabilize workforces” in specific fields like childcare and nursing homes, and $40 million for work training programs, which included “promot[ing] equity and inclusion” across industries, among other programs (Pritzker, 2024). This behavior resembled that of dozens of other states and local jurisdictions across the Nation.

Illinois lawmakers’ approach to this year’s budget deficit was typical of their behavior when graced with billions of dollars in budget surpluses in the preceding years. In February 2024, when it appeared possible that the state would have $400 million more in its budget than originally anticipated, legislators were faced with the options to either create “other initiatives or to push forward as a balance in fiscal year 2025.” Predictably, “the rank-and-file lawmakers nearly always view end-of-year balances as a potential funding source for their legislative priorities” (Nowicki, 2024). Such a disposition toward stewarding taxpayer money explains why the state aggressively used COVID-19 funds to expand government instead of addressing its structural deficits. In addition to its pension liabilities, Illinois’s deficit is largely attributed to increases in its structural and mandatory expenditures, such as “K-12 education, human services, health care…and government health insurance” (Nowicki, 2024).

On the local level, the City of Los Angeles, California, exemplifies the irresponsibility of municipal jurisdictions and their capacity to grow government, even though the city is subject to local government provisions of Proposition 13. Reports submitted to the Department of the Treasury show that Los Angeles spent more than 60 percent of its $1.3 billion ARPA funds on “government operations” through 2023, which is significantly higher than the national total of 39.5 percent spent on this category across all states. ARPA funds represent 11 percent of the city’s 2022–2023 total fiscal year budget of $11.78 billion. Of ARPA funds used in the government operations category, about $770 million was used for hiring and wages in 2022 and 2023, long after the initial COVID economic shock ended (Brookings Institution, 2024). Flush with cash, the city was able to grow its 2023–2024 budget by 11.6 percent—some $1.37 billion—from the preceding year, figures closely mirroring its total ARPA funds (LA CAO, n.d.). Other projects included $20 million for preschool programs, $10 million for senior nutritional aid programs, and more than $75 million for new parks, “Play Streets,” and open spaces (Brookings Institution, 2024).

Los Angeles’s looming budget deficit also shows how the post-COVID growth in government compromises funding for the city’s essential services with its irresponsible ARPA spending. By 2024, the city faced a multi-year budget deficit and approved a modest 2 percent reduction from the previous fiscal year to $12.8 billion, which is still 8.6 percent higher than the 2022–2023 budget (Tat, 2024). Whatever the worthiness of these spending programs, their net effect is to create a fiscal crunch when temporary funds are used to create and expand long-term fiscal commitments. As the Los Angeles chief administrative officer admitted, the city’s 2024 deficit was due to overspending and decreased revenues; he bluntly stated: “We’re not in a recession. This is not COVID. This is a budget deficit that we made here in City Hall” (Haskell, 2024).

Still, other jurisdictions throughout the Nation used COVID-19 relief funds to grow the government and fund many questionable programs. Washington State, for example, used $40 million of its ARPA funds to issue $1,000 checks to immigrants in irregular situations otherwise “unable to access federal stimulus programs due to their immigration status” (Johnson, 2024a). Los Angeles County, which, like the city of Los Angeles, falls under the local protections in California’s Proposition 13, grew government in several sectors. New initiatives included “home visiting programs” at the cost of $5.5 million, “free” legal support for small businesses at a cost of $3 million, and a $12 million career training program. Clearly, expenditures went beyond pandemic economic relief as the county itself instead called ARPA “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address LA County’s most urgent inequities” (LA CEO, n.d.).

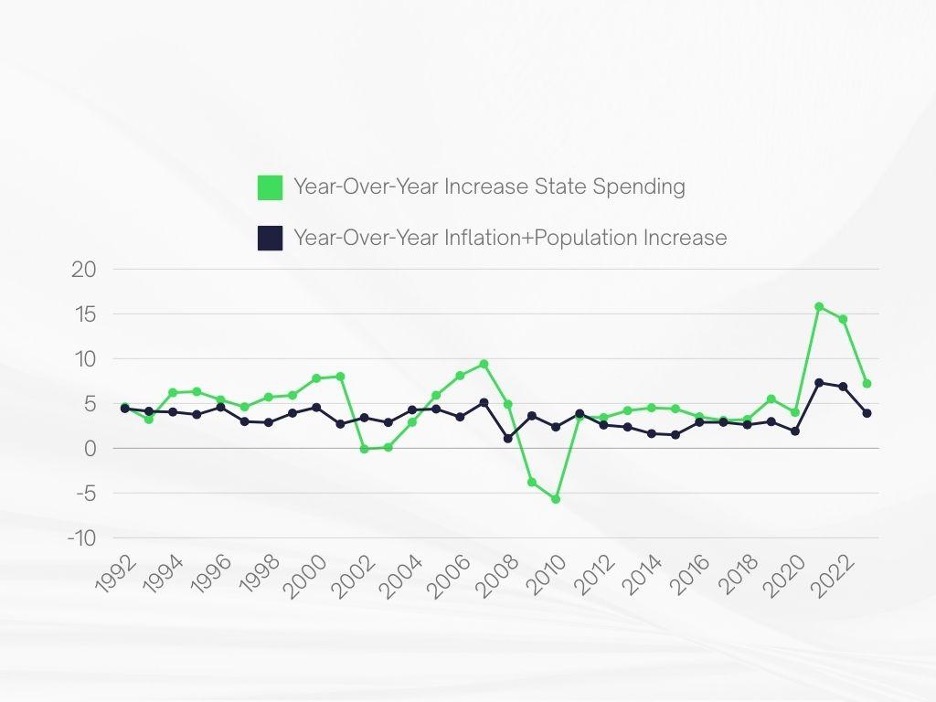

Figure 1 below illustrates how dramatically year-over-year total state spending has consistently increased for the last three decades, but most dramatically since the pandemic. Before 2020, no state during this period increased total spending by more than 10 percent. Yet in 2021, the year the ARPA was enacted, state spending increased a staggering 15.5 percent and continued to rise in the ensuing two years. Note that the one year that state spending declined year-over-year coincides with the years of the Great Recession after funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act were exhausted.

The above figure shows year-over-year percentage increases in total state expenditures, which include “spending from general funds, other state funds, bonds, and federal funds to states” (represented by the green line) compared to the year-over-year growth in the percentage of residents plus real inflation during the same time period (represented by the black line) (Macrotrends, n.d.; National Association of State Budget Officers, 2024; Srinivasan, 2025 ).

Comparing the two lines, annual state government spending grew faster in all but one year—2012—than the rate needed to keep delivering the same level of services if pegged to population growth (National Association of State Budget Officers, 2024). Indeed, states have only increased spending since 2020 in no small part due to nearly $1 trillion in transfers from the federal government. For perspective, the Tax Policy Center reports that state spending grew 36 percent more in the three years from 2019 to 2022 than in the previous decade between 2008 and 2018, when spending increased only 31 percent (Auxier, 2023). Note that 2019 was the last full year before the pandemic-era monetary stimulus.

Some jurisdictions, however, did act comparatively responsibly with their federal pandemic funds. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), “several states enacted cuts to their personal (and in some cases corporate) income tax systems in 2021 and 2022, with especially dramatic cuts in states that include Arizona, Georgia, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina” (Hinh, 2023). Although ARPA initially prohibited its funds from being used for tax cuts, subsequent litigation eased these restrictions. The CBPP report is, in fact, critical of states using ARPA funds for tax cuts, claiming that they failed to use the windfall to make “investments” in their states’ infrastructure and expand programs for underprivileged groups. It also claims that tax cuts make funding for government programs less likely, given the possibility of less revenue. Yet, what the CBPP and ARPA’s advocates call a mistake is precisely the virtue of these states’ actions. Instead of using temporary funds to create long-term liabilities and commitments, these states resisted the urge to expand government. Rather, they reduced the money taxpayers remit to the government, allowing the free market to make its own worthy investments according to needs that the government would be unable to determine and manage with as much competence. As a result, these states have an opportunity to continue growing their economies and infrastructure long after the ARPA funds end.

Far from addressing the fallout from the pandemic, this COVID-era transfer of funds from the federal government to state and local governments, especially in the ARPA, was clearly a pretext to expand the government’s reach and scale in sectors completely unrelated to public health. States that used COVID relief funds to establish long-term commitments have not so much invested in their infrastructure but limited current and future private sector investment by growing government. The massive transfer of funds during the COVID pandemic to the states and the corresponding expansion of the government’s footprint beg for an explanation of why states were unable to resist public sector growth.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), the federal government transferred an unprecedented sum of money to state and local governments, long after the fiscal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic had stabilized.

- States and local governments largely acted irresponsibly with these funds and used the pandemic as a vehicle to permanently expand the size of government, creating new programs and long-term fiscal commitments with temporary appropriations.

- As ARPA appropriations are exhausted, state and local governments now face projected multi-year budget shortfalls and are looking to taxes and other revenue-increasing measures to address the liabilities they created.

The Absence and Failure of Existing State Taxpayer Protections

It is important to note that the fiscal reckoning many states are facing due to their expansion during the COVID-19 era occurs in the context of state and local governments’ consistent growth in the years preceding the pandemic. Irresponsible tax and spending habits were not limited to a time after 2020 and were only exacerbated by the nearly $1 trillion transferred to states from the federal government. Indeed, these trends point to the failure of many states with TELs to stem government’s growth and to the capacity of state leaders to circumvent laws and increase taxes beyond specified limits. If anything, the post-COVID public sector growth strengthens the argument for stronger TELs and the need for improved protections.

At the beginning of COVID-related government spending in 2020, 32 states had TELs, which raises the question of why existing TELs failed to control the burden of government. As noted previously, TELs are self-imposed limits on government receipts and/or spending. So, why did existing TELs, of many different types, fail to control the burden of government?

The very nature of these laws—either constitutional amendments or regulations—and the mechanisms by which states go about imposing these limits are diverse. According to the Tax Policy Center, “24 states imposed limits on state spending…19 states limited state revenue, and 12 states limited both,” while one other state-employed alternative TELs are not strictly defined as either revenue caps or spending limits (Tax Policy Center, 2024). Certain states strengthen their restrictions by imposing a high threshold for the vote of citizens or the legislature to raise taxes, a practice called “binding.” Restrictions on revenue and spending are often carried out through prescribed formulas. Many of these formulas peg revenue to certain metrics like inflation and population growth. Other limits fix revenue or spending levels to a certain year—often the year of passage—and allow only incremental, fixed-formula increases. Certain TELs, like Colorado’s TABOR, are distinguished by imposing mandatory taxpayer refunds on revenue that exceeds specified limits. Finally, certain states have chosen to elevate their TEL protections to the level of state constitutional authority. Of course, the nature of these TELs and their various mechanisms largely determine their success at limiting the government’s burden and avoiding progressive erosion of their protections.

As noted, not all TELs employ the same mechanisms for restraining government growth. The methods noted in the previous paragraph are identified by the Tax Policy Center as the most common. States with TELs employ one of these methods or combinations of them to accomplish their goals. The table below provides an overview of which mechanisms states with TELs employ to implement their respective limitations:

Table 1: Tax and Expenditure Limits by State (2020)

|

Spending Limits |

Revenue Limits |

Supermajority Requirement to Bypass |

Constitutional Provision |

|

|

Alaska |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Arizona |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Arkansas |

X |

X |

||

|

California |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Colorado |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Connecticut |

X |

X |

X[1] |

|

|

Delaware |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Florida |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Hawaii |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Idaho |

X |

|||

|

Indiana |

X |

|||

|

Iowa |

X |

|||

|

Louisiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Maine |

X |

|||

|

Massachusetts |

X |

|||

|

Michigan |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Mississippi |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Missouri |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Nevada |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

New Jersey |

X |

|||

|

North Carolina |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Ohio |

X |

X |

||

|

Oklahoma |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Oregon |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Rhode Island |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

South Carolina |

X |

X |

||

|

South Dakota |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Tennessee |

X |

X |

||

|

Texas |

X |

X |

||

|

Utah |

X |

X |

||

|

Washington |

X |

X |

||

|

Wisconsin |

X |

X |

The above table provides a survey of which mechanisms states with TELs employ to control the burden of government. Note that some states employ multiple mechanisms. (Fiscal Rules, n.d.; Tax Policy Center, 2024; Urban Institute, 2024).

This exponential growth of state and local government persisted after the COVID-19 pandemic and the ARPA appropriations, despite the use of varied mechanisms to limit spending that were employed in different combinations in states with diverse populations and economies. California and Missouri provide test cases to explain broadly why and how TELs often prove insufficient. As noted in the introduction, the TELs in California and Missouri are noteworthy for how they have proven ineffective at keeping taxes low and government growth in check. In California, Proposition 13 has been progressively weakened by voter initiatives and mounting exceptions for issuing taxes and bonds, depending on how the revenue is used, which allows the lowering of voter thresholds for imposing taxes. In Missouri, lawmakers subverted the tax base mandated by the Hancock Amendment to determine yearly revenue caps and have made backdoor appropriations in the form of tax incentives for preferred policy priorities and special interests. States considering new or stronger TELs would do well to heed lessons from the failures of these two laws.

California’s Prop. 13 and an Initiative Process Hijacked by Special Interests

Proposition 13, an initiative California voters passed in 1978, was hailed at the time as a harbinger of a nationwide tax revolt that would endure through successive decades. The protections the law imposed for state taxpayers were far-reaching and generally popular, given that it passed with some 65 percent of the vote (Baldassare et al., 2018) and that as recently as 2019, the Los Angeles Times referred to it as the state’s “political third rail” (Skelton, 2019). Initially, Proposition 13’s protections were expansive. They permitted property reassessments for the purpose of determining taxes to take place only when properties were sold or substantively improved, limiting increases to 2 percent per year. The law also required a two-thirds vote of the legislature to raise taxes and two-thirds of voters to approve so-called “special taxes,” including certain bond measures, that municipalities like school districts, cities, and counties can impose (Skelton, 2019). Voters continued to extend the law’s protections through the 1990s, allowing children to inherit their parents’ property tax basis with Proposition 58 in 1986 (California State Board of Equalization, n.d.-a.) and extending this exception to property transferred from grandparents to grandchildren with Proposition 193 in 1996 (California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 1996a). Proposition 218, also approved in 1996, prohibited local governments from imposing assessments on property owners for local taxes and fees that were otherwise excluded from Proposition 13, while also further limiting local authorities from enacting taxes without voter approval (California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 1996b).

Yet, in the last 24 years, voters have progressively chipped away at Proposition 13’s protections, with politicians and special interests using California’s initiative system—ironically, the same mechanism used to approve Proposition 13—to approve one exception after another to the law’s protections. Most notably, voters elected to lower the threshold for issuing bonds for public school funding with Proposition 39 (2000) (California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2000) and passed Proposition 19 (2020), which subjected heirs of a family home to property tax reassessments if they did not claim their inherited property as their primary residence (California State Board of Equalization, n.d.-b). For several years, politicians and left-leaning advocacy groups have advocated for a “split-roll” reform, by which commercial property would no longer be protected by Proposition 13’s protections from property tax reassessments, meaning their assessments would consistently be reassessed according to current market rates (Baldassare et al., 2018).

As noted above, the key to Proposition 13’s weakening is the capacity of California’s leaders to manipulate its initiative petition system for the sake of expanding government. One recurrent promise is these tax-friendly politicians’ recourse to special projects, such as education and public-school funding, to convince voters to carve out yet another Proposition 13 exception, as with the successful passage of Proposition 39 in 2000. California’s leaders have aggressively pushed additional taxes and bonds for public education, a feat that Proposition 39 made easier. In 2019, the occasion of the 40th anniversary of Proposition 13’s enactment, the Public Policy Institute of California reported that a majority of Californians, while generally favorable to Proposition 13, would see fit to repeal many of its protections to fund K-12 education (Baldassare et al., 2018). By appealing to special cases, such as public education, state and local politicians have, year after year, approved more and more Proposition 13 exemptions. Doing so was made even easier in 2011, when the legislature moved all ballot initiatives to the general election rather than lower turnout primary elections, with the stated intention of ensuring greater turnout for constituencies more favorable to their ballot measure positions (Mulkern, 2011). Californians are thus plagued with dozens of state initiatives on the same ballot and voter guides that describe these ballot measures consistently numbering more than 100 pages (Kamal, 2024).

Missouri’s Outdated Hancock Amendment Unable to Keep Pace with State Economic Trends

Using ballot measures and misleading voters is not the only way states have weakened TELs. In Missouri, the so-called Hancock Amendment (1980) includes several important taxpayer protections, such as a cap on total state revenues (TSR) tied to a fraction of income set in 1981. The amendment also permits revenue increases based on the personal income of state residents as provided by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The state must refund revenues in excess of 1 percent of the given year’s ratio and the law also requires voter approval for specifically defined tax increases. A 1996 amendment subjected repeals of tax cuts to the Hancock Amendment and limited the threshold for the types of taxes the legislature is still allowed to raise. Through the 1990s, the Hancock Amendment was effective at restoring money to taxpayers and limiting the government’s burden, as the state issued $971 million in direct refunds to individuals and businesses between 1995 and 1999 (Keller, 2022). To avoid issuing yearly refunds, the state reduced and even eliminated certain general revenue taxes (Kirkland, 1997).

Still, lawmakers exploited shortcomings in the Hancock Amendment’s classification of revenue—shortcomings that have, at present, caused the formula for determining revenue caps to become largely ineffective. As noted above, the amendment only applies to TSR, which means that “the funds must be received into the state treasury and [are] subject to appropriation” (Kevin-Myers & Hembree, 2012). State officials have progressively weakened the Hancock Amendment through accounting gimmicks that recategorized certain revenue as funds not subject to the amendment. The 1996 tax hike limits further constrained the amendment’s effectiveness through its enforcement mechanism that looks at projected revenue increases, not the actual increases. Thus, the legislature can further circumvent these protections by phasing in larger tax hikes over multiple years.

State politicians have also undermined the formula the law imposes for yearly revenue caps, using tax incentives to, in essence, make roundabout appropriations. They have done so by expanding tax credits for special projects, such as for developers who build low-income housing, among other projects. The practical effect of these credits, of course, is preferential treatment for specific policy priorities funded with diverted taxpayer money that never entered the state treasury (Keller, 2022). Given that these funds are never collected into the TSR, the revenue basis used to calculate the yearly caps is consistently lowered. Just as problematic, if the state brings in excess revenue and then spends that money via tax credits, it is counted as contra revenue[2] and thus does not count toward the Hancock Amendment limit. This gimmick makes refunds much less likely.

Also, the ratio used to determine revenue limits has proven itself largely obsolete. As noted above, the amendment provides a 1980 basis of Missourians’ total personal income, while revenue caps are adjusted accordingly. However, personal income has risen more than 650 percent since the amendment’s adoption, in contrast to a 495 percent increase in TSR. Strong personal income growth is certainly a factor contributing to the widening gap, but numerous tax cuts, namely to the state income tax rate, have also widened the gap. While cutting income tax rates is good, lowering them should not undermine the revenue caps that prevent the government’s growth. Given these developments, the ratio of revenue to personal income is unlikely to be reached in the near future,, and Missourians will go longer periods without these mandated rebates (Keller, 2022). Combined, these issues have exposed the Hancock Amendment’s weaknesses: an outdated formula for revenue caps, revenue categorizations that politicians exploit to erode the basis for determining TSR, and weaknesses in the criteria for determining TSR, which allow for backdoor appropriations by passing tax credits to ensure revenue is never deposited into the state treasury. Together, these factors have rendered this law mostly toothless.

Nonexistent and Impotent Taxpayer Protections Subject Taxpayers to More Government Growth

High-tax states with TELs have, in the most recent election cycle, proposed billions of dollars in bond measures and tax increases and corresponding increases in government programs. The quintessential example is California, which, despite its Proposition 13 protections, continues to push bond measures and tax increases. Yet, as analyzed in the previous section of this paper, California is not alone in facing budget deficits after massively expanding its state government. As states reel with poor decisions made both before and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for stronger and updated protections is increasingly evident.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- TELs in 32 states have proven largely ineffective at limiting the burden of government, especially in the wake of federal monetary transfers in the ARPA.

- California’s Proposition 13 and Missouri’s Hancock Amendment represent the two predominant mechanisms for how TELs proport to reduce the burden of government and are examples of how these mechanisms have fallen short.

- Special interests have progressively weakened Proposition 13’s tax limitations by manipulating California’s initiative system for the sake of expanding government. The Hancock Amendment’s restrictions on state revenue have been rendered ineffective through lawmakers’ accounting gimmicks and outdated formulas for determining revenue limitations.

Colorado Shows How to Preemptively Stem Government’s Growth

Among those states with TELs, Colorado’s TABOR is widely considered the strongest and most effective at reducing the burden of government, and its methods for doing so are comprehensive. First, as noted in the introduction, TABOR limits the state’s growth in taxpayer-funded spending to the previous year’s CPI in its largest metropolitan statistical area, plus projections for population growth for the coming year. For local governments, the annual TABOR limit is tied to the various statistical areas’ CPI plus the increase in real property values, calculated by yearly assessments. The state limit is enforced mostly through a refund mechanism that TABOR mandates, requiring that receipts that exceed the limit be refunded to taxpayers. These refunds may be enacted in a host of forms, including tax cuts or direct payments. Doing this is a constant reminder to lawmakers and taxpayers alike of the principle that state revenue belongs, in the first instance, to the state’s residents who fund government (Bell Policy Center, 2002).

Second, TABOR requires voter approval of new taxes. The language itself is very explicit, leaving voters to decide “any new tax, tax rate increase…or extension of an expiring tax, or a tax policy change directly causing a net tax revenue gain to any district” (Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights). Unlike California’s law, TABOR requires tax hikes to be explicitly identified on the ballot, including in the title and at the beginning of their official description. Doing so has limited politicians’ discretion to deceive voters with misleading ballot initiative titles that emphasize policy preferences over the reality of tax increases. These requirements also tie any new policy priorities that would require new revenue with their corresponding tax increase, reminding voters as they cast ballots that their money will fund any growth in government.

Third, TABOR limits the state’s options for imposing taxes by prohibiting taxes that are common elsewhere in the Nation. Specifically, the amendment prohibits localities from imposing income taxes and the state from collecting property taxes. It also prohibits transfer taxes on real estate. Especially noteworthy is TABOR’s requirement that the state set “all taxable net income to be taxed at one rate” (Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights). If the burden of tax hikes were felt equally among all taxpayers, those who wish to grow government could not argue that only high earners would be affected by proposed tax increases.

Finally, TABOR is especially notable in its comprehensiveness as it applies to all state and county taxing authorities, including school and public safety districts, transportation authorities, and other regional bodies (Ginn, 2023). It also applies to previously enacted TELs, subjecting these protections to voter approval, thus making it harder for lawmakers to weaken them. The most notable practical effect of this requirement was enshrining a state law that prohibits general fund appropriations from exceeding 6 percent of the previous year’s appropriation, reserving to the voters whether this limit on government growth could ever be lifted.

Given these mechanisms, TABOR’s results in accomplishing its stated goal to “restrain the growth of government” (Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights) are remarkable. In the decade before TABOR’s approval, Colorado’s state spending grew at roughly double the rate of inflation, yet in the decade after its enactment, state spending grew only by TABOR’s prescribed formula of population growth plus inflation (Stooksberry, 2019).

Yet less appreciated is TABOR’s positive effect on economic growth. In fact, in the first 10 years after TABOR’s approval, Colorado’s economic expansion was unprecedented. During the 1990s, Colorado ranked third among states in gross state product (GSP) growth and fourth in employment growth. Astoundingly, Colorado’s per capita personal income growth between 1992 and 1998 grew more than 46 percent, the fastest in the Nation (Bell Policy Center, 2002). Indeed, the state’s population exploded by nearly a third, according to the 2000 Census (Perry et al., 2001). The marked economic growth continued in the following decades as between 2001 and 2023, in the Denver metro area—the state’s largest—gross domestic product (GDP) grew some 77.9 percent from $134.53 billion to $239.40 billion in 2017 dollars (Statista, 2024). Still, certain studies—while recognizing the correlation between the state’s increased economic vitality and TABOR’s enactment—assert that “there is no evidence that either the passage of TABOR or the implementation of refunds changed the rate of GSP [Gross State Product] or employment growth in Colorado” during its first 10 years (McGuire & Rueben, 2006). Another study by the Bell Policy Center claims the growth was widespread throughout the Western United States during the first 10 years since its enactment, and, thus, the growth was part of a “regional economic expansion.” The study also claims that most states had TELs during these years and that TABOR, while being the most stringent, would not have been distinguished among these limitations (Hedges, 2003).

Yet far from proving that TABOR had little to no effect on Colorado’s unprecedented economic expansion, the study’s admission that TELs existed in “all the fastest growing states” during this time can also compellingly be viewed as evidence that TELs are effective at spurring growth, keeping taxes low and restraining government growth. In fact, the Denver Post reported that in Colorado, the government’s share of the state’s employment was 19.5 percent in 1980—the first year of a challenging economic period for the state—but had fallen to 16.3 percent by 1996, while, within the private sector, the service sector rose from 20.3 percent to 29.8 percent during the same time period (Blount, 1998). Clearly, as the government retracted its footprint, it allowed for the private sector to expand and create greater wealth in the state. Additionally, the western states of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah, which make up the region where 1990s economic expansion was fastest, are low-tax states with a limited public sector. Nevada does not impose a state income tax, and Arizona passed five separate income tax cuts during the 1990s (Charney, 2013). Clearly, the states experiencing this strong regional economic growth had the commonality that their state governments’ footprints were progressively and consistently restrained, allowing private enterprise and investment to expand jobs and productivity.

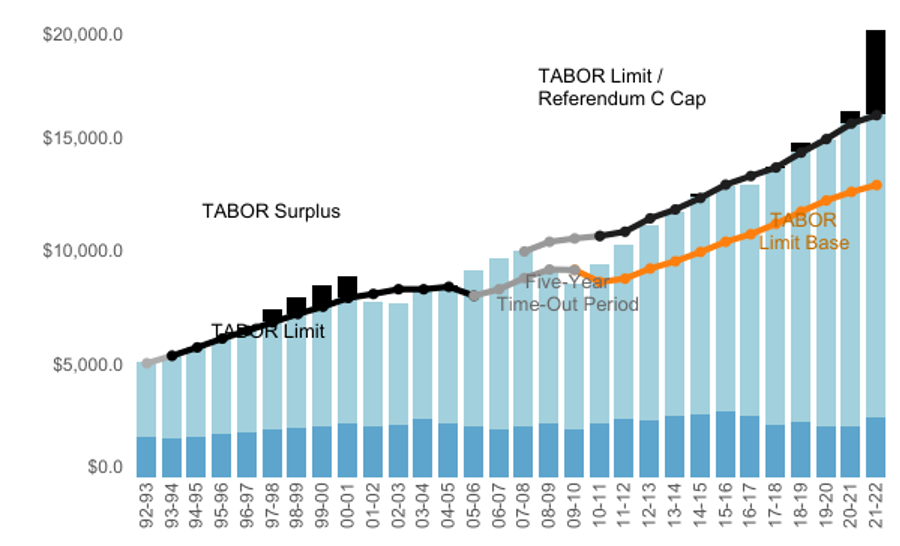

The following graph illustrates TABOR’s success, demonstrating that surpluses consistently grew relative to the TABOR limits between the 1992–1993 and 2021–2022 fiscal years.

The above figure depicts how the gap between the TABOR limit base and budget surpluses widened relative to the TABOR limits between the 1992–1993 and 2021–2022 fiscal years (Colorado Legislative Council Staff, n.d.). Note that Colorado voters suspended TABOR limits in a 2005 referendum from 2006–2010, providing for the variance in surpluses relative to the imposed limit (Colorado Department of the Treasury, (n.d.))

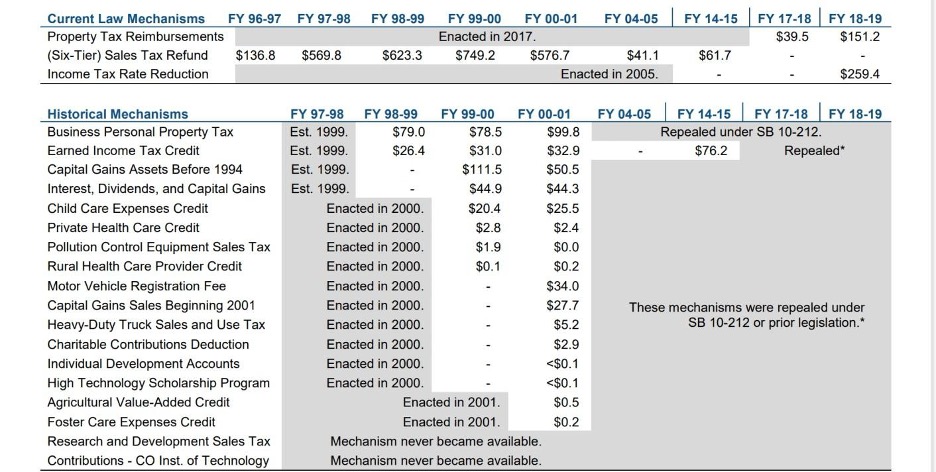

Given the above-noted budget trends, TABOR began yielding tax refunds in 1997 when, for the first time, the state’s revenue exceeded the law’s limit. For the remaining years of TABOR’s first decade, Colorado’s revenue continued to exceed its statutory limit, and the state began to remit money back to its taxpayers through nonpermanent tax rebates and credits (Bell Policy Center, 2002). Since then, TABOR has consistently delivered direct and tangible benefits in the form of rebates beyond the caps on government revenue that the law imposes. In the form of tax cuts, direct payments, and fee reductions, among other methods, TABOR has forced the state to restore to the taxpayers their own money. As recently as 2022, Colorado issued direct reimbursements to taxpayers, sending $750 checks to individual taxpayers and $1,500 to joint filers as the state’s revenues exceeded the TABOR limit by $1.7 billion for the 2021-2022 fiscal year (Wilson, 2023). For tax year 2023, the state authorized a refund of $800 for single filers and $1,600 for joint filers for taxpayers who claimed a state sales tax refund on their tax returns (Colorado Department of Revenue, n.d.-a)). In 2021, the state issued a temporary reduction of 0.5 percent of its income tax (Colorado Department of Revenue, n.d.-b). The following table produced by the Colorado Legislative Council staff illustrates the various means by which TABOR’s rebates have been implemented since its enactment:

The above table from the Colorado Legislative Council notes the various historical means by which surplus TABOR funds have been refunded to taxpayers (Sobetski, 2022). Note that Colorado voters suspended TABOR limits from 2006–2010 (Colorado Department of the Treasury, (n.d.)).

The mechanisms by which Colorado has returned money to its taxpayers have been consistent since TABOR’s enactment, proving its efficacy to taxpayers with consistent benefits. Far from being vague and remote, TABOR benefits have been tangible—returning money to or keeping money in the hands of taxpayers.

At the same time, TABOR has not been immune to modifications and weakening of its taxpayer protections. When it was first approved, TABOR covered some two-thirds of the state’s spending, yet it covered less than half of state spending in 2023 (Ginn, 2023). More recently, fully within TABOR’s limitations, state lawmakers have directed tax rebates to specific interest groups. Between 2019 and 2022, the governor approved more than $600 million in tax incentives for specific pet projects, including $40 million to refund residents who switch to electric garden appliances (Colo. SB 23-016). Two other laws approved in 2023 provide rebates to electric vehicle owners (Colo. HB 23-1272), and another expanded the state-earned income credit (Colo. HB 23-1112). Regardless of the prudence or the worthiness of these or any policy choices, these tax incentives create yearly tax expenditures and, thus, subvert TABOR’s stated goal to restrain the growth of government spending and are funded from the TABOR yearly surpluses, reducing the refunds enjoyed by a broader taxpayer base (Bishop, 2023).

While detractors have referred to TABOR as a set of “inflexible rules that make it [state government] unresponsive and less effective” (Hedges, 2003), this rigidity is precisely its strength in withstanding the same erosions that politicians and courts have imposed on TELs in other states. If anything, the aforementioned weakening TABOR has sustained in its 30-year history indicates that its rigidity has proven insufficient to deter lawmakers from narrowing its scope and manipulating tax rebates for special interests. TABOR’s ultimate success, however, communicates to politicians, state taxpayers, and the business community the policy principle that the government is funded by their money and that any surplus above reasonable limits belongs to the taxpayers. Indeed, Coloradans seem to have incorporated this concept, as opinions of TABOR have remained favorable despite the state’s shifting political preferences since the amendment’s enactment 30 years ago. As recently as 2023, Colorado voters rejected Proposition HH, a ballot question that would have weakened TABOR by, among other things, increasing the state spending limit and thus reducing the TABOR surplus in exchange for lower property tax rates. As Vance Ginn writes in the National Review, although “spending determines the ultimate burden of government…had Prop HH succeeded in raising the spending cap, the state budget would have expanded, rendering it impossible to lower income-tax rates without affecting the budget” (Ginn, 2023). Just as in 1992, Colorado voters continue to reassert their preference for a restrained and less burdensome government.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- TABOR’s sweeping restrictions on new taxes and a robust refund mechanism brought Colorado’s spending under control from twice the rate of inflation in the decade preceding its approval to its strict formula of population increase plus inflation in the decade after its enactment.

- TABOR unleashed staggering economic growth, notably in its first decade, as public sector employment receded and private sector jobs grew. Personal income in Colorado grew faster than that in any other state in the first four years after the law’s enactment.

- TABOR has succeeded in cementing into Colorado’s civic ethos the principle that tax revenue belongs to the taxpayers. Voters have rebuffed recent attempts to weaken TABOR’s protections.

Toward Platinum Standard Tax Expenditure Limits

While TABOR is largely recognized as a “gold standard” among state-level TELs, and while it provides an excellent platform in its apparatus and goals for other states to emulate and build upon, there are many ways to create a “platinum standard” by which states can enact TELs with a greater scope of authority to limit spending. Other states may find the following suggestions helpful as they seek to incorporate TABOR’s strengths and fortify the areas in which their own TELs have been weakened.

1. Channel Budget Surpluses to Permanently Reduce Tax Rates

TABOR’s success in growing surpluses of tax revenue relative to the amendment’s permitted spending provides an opportunity to move beyond merely restraining the growth of government and calls for a paradigm shift that rejects the presumption that government will inevitably grow or must grow. This can be accomplished by shifting toward what is referred to as “sustainable budgets.” Under these plans, budget surpluses can be used to “buy down the income tax rate” without affecting current state spending by both capping revenue and imposing a growth cap on spending of all state funds (Ginn & Murrey, 2023). Colorado provides a compelling test case for why, despite the success TABOR has had in reducing that state’s burden of government, additional reforms are needed. As Vance Ginn notes in the National Review:

[Since TABOR,] appropriations of all state funds have increased by 74.2 percent, compared with an increase of just 46.5 percent in population growth plus inflation over the last decade. This has resulted in the state appropriating $4.2 billion more in just fiscal year 2023–24 than if it had been limited to the rates of population growth plus inflation over time, amounting to higher spending and taxes of about $3,300 per family of four. The summed difference each year in all state funds above this metric over the decade amounts to $16.3 billion, or $11,300 per family of four (Ginn, 2023).

These proposals, then, would mirror the cap that TABOR imposes on revenue (population growth plus inflation) and impose the above-described restrictions on appropriations, which TABOR does not currently impose. Doing so would effectively address the inadequacies that have allowed the difference between TABOR’s spending cap and tax revenue collected to grow consistently since TABOR was enacted. In other words, the proposal discussed here, while acknowledging that it would be better not to increase the budget at all, would still work to freeze spending to a formula that has already proved effective for revenue limits.

2. Enhance Existing TEL Restrictions to Address New Fiscal and Budgetary Trends

A platinum standard TEL must prevent gimmicks such as directing tax incentives and credits to special interests, many of which are a workaround meant to tap into a surplus that TELs like TABOR produce. As this paper has argued, these tax credits constitute policy choices that should be decided in the regular appropriations process. Indeed, many of these tax credits and incentives are extensions of government policy priorities. These tax credits and other workarounds have led to a progressive weakening of TABOR, effectively reducing the revenue subject to its cap. The Hancock Amendment was weakened by similar schemes, and Colorado now risks the same. While it may be implausible for all of these tax credits to be eliminated, future credits must be severely restricted in statute. Additionally, instead of these credits being classified as contra revenue, they ought to be classified as what they are: spending.

Another area that should be strengthened is the formula used to determine spending and revenue caps. Shifting economic and fiscal realities mean that these formulas may become outdated over the ensuing decades in ways that lawmakers may not anticipate. This includes formulas that do not keep pace with personal income growth that, for example, has often grown faster than TELs fashioned in the latter 20th century foresaw. Thus, over time, the formulas are less robust at reducing the burden of government. Platinum standard TELs must allow for, if not mandate, an updating of the formulas used to address economic factors, changes that must always favor stronger taxpayer protections and reduce the burden of government. Doing so will ensure consistent updates to TELs and not allow for prolonged periods when outdated formulas, in effect, limit the very protections they were meant to enshrine.

3. Address Structural Spending Commitments to Reduce Government’s Overall Burden

Working with less revenue will force state and local jurisdictions to make important policy decisions about what programs and spending decisions they wish to prioritize and to reevaluate the necessity of these initiatives. Forcing a relative scarcity, particularly given balanced budget requirements, has proven effective in encouraging these decisions. A key example of a state making these decisions comes from California.

Ten years after Proposition 13’s enactment, voters approved Proposition 98, which provided a guaranteed level of funding for K-14 education (including community colleges). This initiative set the floor for these appropriations at about 40 percent of the state’s 1988 budget and mandated a formula for determining increases based on growth in student enrollment and per capita personal income growth (California Legislative Analyst’s Office, 2005). While the prudence of this spending decision is debatable, it represents a decision—in this case enacted by voters themselves—about how to spend increasingly limited tax revenue and an affirmative acknowledgment that there will be less revenue for other government undertakings within a state’s yearly budget.

K-14 education in California is funded primarily through property tax revenue and appropriations from the state budget and was thus especially affected by Proposition 13’s limits. It is a telling example of the budgetary decisions state and local governments must make when they are deprived of perpetually increasing tax revenue. While states will inevitably confront these budgetary decisions with strong TELs, these debates must be accelerated to prepare both residents and lawmakers for what may be difficult decisions about the government’s footprint. Mandating budgetary frameworks like the sustainable Colorado budget proposal mentioned above would help spur these conversations and should be incorporated into platinum standard TELs.

4. Prohibit Narrow Exceptions to Tax Restrictions and Improve the Ballot Initiative Process for Raising Taxes

As California’s experience with the progressive weakening of Proposition 13 demonstrates, special interests are often successful at convincing voters to carve out exceptions for these constituencies while, at the same time, lawmakers are content to generate additional revenue. Appealing to voter preferences, such as when California voters reduced the threshold to raise local revenue for K-12 education in Proposition 39 (2000), proved sufficient for voters to weaken Proposition 13 dramatically. TELs must apply to all taxes and revenue-generating measures without regard to the purpose for which they are designated. Thus, a stronger TEL would have offered voters a choice: either lower the threshold for raising all taxes and bonds or not lower the threshold at all. Given that the strongest TELs are constitutional amendments, any subsequent ballot initiative seeking to raise taxes or alter the TEL in question should be a constitutional amendment. Allowing voters to face the reality of higher taxes would help them more deeply question the need for any new revenue. Any subsequent ballot initiatives would have to fall under one of two categories:

First, if the ballot initiative sought to increase spending in a specific area, then the state would have to interpret the ballot initiative in a way that was compatible with the TEL. That is, spending in that specific area would rise according to the initiative’s language, but total spending would still be subject to any of the TEL restrictions. Thus, the ballot initiative would merely be interpreted as a voter directive about what the legislature should prioritize instead of a directive about increasing the total size of government.

Second, ballot initiatives that propose to increase the total size of government beyond the TEL limit would have to include standardized ballot language that explicitly posited that approving the measure would mean higher total government spending and that voters would not receive a scheduled tax cut. Ballot propositions concerning tax hikes would have to be explicitly labeled as tax increases, with requirements and language as strong as, if not stronger than, the verbiage that the TEL stipulates. The requirements that TABOR imposes on initiatives in Colorado are a strong foundation, especially in prescribing strong language for ballot titles and descriptions that explicitly designate the measure as a tax increase.

Too often, tax increases are obscured in ballot measures that emphasize a benefit that is supposedly offered. A recent example is the previously mentioned Proposition 19, which California voters approved in 2020. The law requires continual residency in an inherited property to inherit a predecessor’s property tax basis.[3] Real estate vendors, including the California Realtor Association, who have an economic interest in forcing the sale of property, failed in 2018 to convince voters to pass a measure similar to Proposition 19 (Blake, 2020). Yet two years later, adding a provision that provided relief for wildfire victims by allowing them to transfer their property tax basis—thus allowing them to relocate from high-risk areas—proved to be sufficient to convince voters to approve the initiative. While a subset of California taxpayers affected by the state’s increase in wildfires received a nominal benefit, Proposition 19’s ultimate effect was to remove a key protection that helps state residents amass generational wealth. To avoid similar gimmicks, more states should adopt stronger language in their ballot measures to prevent advocates of tax hikes from highlighting supposed benefits and obscuring the reality that more taxpayer money will be seized.

5. Ensure Better Accountability and Oversight of How Funds are Spent

Governments on all levels are notorious for high administrative costs, questionable efficacy, and waste, which should not be surprising given that governments spend money that belongs to citizens with little oversight. Sufficiently strong TELs would provide lawmakers with more incentive to ensure that tax money was spent responsibly and for citizens to hold their leaders accountable for their recklessness. Politicians in states without TELs or with weak taxpayer protections have little incentive to ensure the efficacy of taxpayer-funded initiatives. For example, a recent report showed that a quarter of all costs associated with Washington State’s long-term care insurance plan go to administrative costs, a number that shocked many government watchdog groups as overly expensive (Johnson, 2024b).

The taxpayer funds spent to address California’s homelessness crisis provide a compelling example of why stronger TELs and accountability are needed. In March 2024, voters approved Proposition 1, a measure Gov. Gavin Newsom promoted that would issue $6.4 billion in bonds to pay for increased homelessness services (California Secretary of State, n.d. ). A month later, the California State Auditor released a report on the state’s homelessness spending. The findings are a damning indictment of the state’s generous spending on services and shelter for the homeless. The report found that while California spent $24 billion on homelessness programs between 2018 and 2023, the homeless population expanded some 20 percent during that same period. More shockingly, the state auditor was unable to determine precisely how much of this money was spent and if the programs it funds are effective because the agency charged with overseeing and evaluating these programs, the California Interagency Council on Homelessness, had failed to track and report data since 2021 (Parks, 2024). That the state has a long-standing and burgeoning homelessness crisis is beyond dispute. However, the state has continued to spend more and more taxpayer funds on programs that have failed to stem the problem, let alone resolve it.

While a dramatic example, California’s homelessness spending boondoggle exemplifies the nature of government growth: Programs and agencies continually demand more funds without regard to their efficacy in resolving the issue they were created to address and with little to no accountability for how funds are spent. Although the California auditor’s report was released the month after Proposition 1’s approval, the state’s response to the burgeoning homelessness problem was typical. Knowing even before the audit’s release that billions had already been spent to no effect and with little accountability, California’s leaders continued to demand even more taxpayer money to maintain and expand programs they knew to be ineffectual and wasteful.

States must break the cycle of unaccountable spending, and a fundamental part of doing so is ensuring that public funds appropriated for specific causes are used responsibly and that their effectiveness is constantly evaluated. Commissions seem to do little more than expose countless examples of government waste and of the futility of many state programs as more and more funds are allocated. Recasting these failures in the context of reducing the overall burden of government through stronger TELs may go a long way toward convincing voters and lawmakers that not only are stronger protections needed, but they must also be focused on reducing the government’s wasteful and hapless scope.

Helpfully, the first 100 days of the second Trump Administration’s efforts to reduce the burden of government through the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) at the federal level gives state and local jurisdictions a blueprint to follow. States like Florida, Georgia, and Texas, among others, are already instituting similar programs to identify wasteful expenditures, abolish superfluous public agencies, and reduce government overreach. A prime example comes from Florida in which Gov. Ron DeSantis created the Florida State Department of Governmental Efficiency to do away with “unnecessary spending, programs, or contracts …and recommend administrative or legislative reforms to…eliminate waste in state and local government (Exec. Order No. 25-44, 2025), a mission that echoes DOGE’s purpose. These measures are precisely the procedures for streamlining reductions in state and local spending that strong TELs would compel these governments to undertake.

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Platinum standard TELs should be forward-looking and nimble, able to incorporate economic and political realities that may not be apparent at the time of enactment. They must mandate that tax formulas and revenue caps always be updated in favor of reducing the burden of government.

- When revenue caps are exceeded, platinum standard TELs must require that excess funds be used to reduce tax rates, starting with the income tax. Stronger restrictions on the use of excess revenue on new projects, especially in the form of tax credits, are essential.

- Platinum standard TELs should restrict modifications and piecemeal exceptions to their protections by lawmakers and voters.

- The success of future TELs must be so apparent that they become part of a state’s civic culture, such that even when political realities shift, voters still vote to preserve these protections. Robust refund mechanisms and a progressive lowering of income tax rates are key to manifesting their success.

Conclusion

Ultimately, expanding government redirects resources that could otherwise be used to grow a state’s economy. It diverts money from the private sector, thus stifling economic vitality and population growth. Equally troubling is how poorly the government spends taxpayer money and its ongoing record of failure amidst increasing taxes. Instead of treating revenue as an opportunity to expand government, taxpayers and politicians must intentionally think of these funds as belonging to the residents and businesses who pay taxes. Lawmakers who make spending decisions are stewards of these funds, which do not properly belong to the government.

Replicating TELs like TABOR that consistently have been successful at lessening the burden of government is essential. Stymieing both the exploitation of TELs’ weaknesses and the political manipulation of direct democracy to weaken taxpayer protections would help modernize protections and make them more enduring. Enhancing TELs to platinum standard requirements that reject the presumption that the government will or must always grow, then using surpluses to lower tax rates permanently to zero, would reduce the government’s growth and allow taxpayers to keep their own money. With the increasingly acute and ever-growing burden that state and local governments impose on their residents, shrinking their regulatory apparatuses, eliminating their wasteful and ineffective programs, and removing their authority over citizens’ lives would be a boon for long-term economic growth and freedom.

[1] Connecticut has statutory and constitutional TELs. However, because the constitutional limits do not “define what types of spending are subject to the cap, the exemptions for the statutory TEL are still in place” (Fiscal Rules, n.d.).

[2] Contra revenue represents the deductions from gross sales, providing insight into net revenue. Unlike gross and net revenue, it is recorded as a debit entry (Inkle, 2024).

[3] Before Prop 19, heirs could keep previous property tax bases on inherited property without claiming it as their official residence. Since Proposition 19, heirs are required to continually reside in the inherited home or the property tax basis will be reassessed. Thus, heirs of inherited rental properties or vacation homes or those who may wish to convert a predecessor’s primary residence into a rental home are no longer eligible to preserve their predecessor’s property tax basis.

References