The Federal Government’s Ongoing Reliance on Chinese Technology Must End

Key Takeaways

The United States government (USG) relies on countless vendors, suppliers, services, and consultants that provide a variety of different products for government agencies.

The purchasing decisions of the USG have massive market weight, but even with “Buy American” requirements, cannot counteract the general economic forces that have moved manufacturing and technological knowledge to the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Numerous agencies and regulatory bodies oversee the process of government procurement, from contract rules to technical standards, but Chinese-manufactured products have slipped through the cracks in some in very sensitive areas.

The downstream effects of these procurement decisions are two-fold: an ongoing reliance on Chinese technology at the detriment of American-made products, and the national security risk of building the technological infrastructure of the American government with Chinese products.

China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law (NIL) mandates all Chinese citizens to cooperate with intelligence services or face severe penalties; this requirement has no clear geographic boundaries or restrictions and has the potential to compromise all products that made in the PRC.

Government bodies responsible for suggesting reform have identified these problems, but bureaucratic inertia has stymied such reforms. Genuine reform is possible in the Trump Administration, especially when coupled with continued legislative action and strong Congressional oversight to ensure compliance. Government bodies responsible for suggesting reform have identified these problems, but bureaucratic inertia has stymied such reforms. Genuine reform is possible in the Trump Administration, especially when coupled with continued legislative action and strong Congressional oversight to ensure compliance.

Overview

The rapid expansion of China’s industrial capacity has led to revolutionary changes in the global economy and worldwide supply chains. The proliferation of low-cost, rapid-response manufacturing drawing upon a massive industrial base, combined with the low cost of international shipping, has enabled the People’s Republic of China to become a tech and manufacturing superpower. With this change, the global economy has become increasingly reliant on Chinese-manufactured components and finished products.

Governments are not immune to such incentives, and the United States and its governments at the federal, state, and local levels have become increasingly reliant on goods manufactured in China. Congress has repeatedly attempted to prevent procurement processes from becoming overly reliant on Chinese suppliers; however, these efforts have been gradually undermined by China’s economic strategy and market manipulation.

Most concerningly, the national security and law enforcement components of the government, despite having the most compelling reasons to avoid procuring products from China, have yet to sever their reliance on such imports entirely. Repeated failures to adhere to guidance have revealed that the government’s procurement processes are not equipped to thoroughly vet and investigate suppliers for potential connections to China and specifically the entities in China that are blacklisted for their ties to the CCP, Uyghur genocide, or the People’s Liberation Army.

All Chinese companies, regardless of their direct affiliation with the Chinese state, are required by law to provide data and access to backdoors in their products. As outlined in China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, “all organizations and citizens shall support […] national intelligence efforts,” without any clear boundaries being established as to where that support is required, or if there are any restrictions on what methods citizens or organizations may be compelled to assist such efforts through (China Law Translate, 2017).

Failures in civilian agencies are equally alarming. The threat posed by Chinese-made devices, particularly their potential to introduce unknown vulnerabilities such as unauthorized network access, remote access, or shutdown capabilities, could exploit weaknesses in critical infrastructure, military equipment, and numerous digital systems used by the government. The procurement and integration of such products into government systems must be avoided.

Numerous solutions are viable, but they require cooperation from the federal government’s chief procurement agencies—principally, the General Services Administration—high-level guidance from executive offices such as the Office of Management and Budget, leadership and innovation from standard-setting bodies such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and execution of responsible procurement practices by individual agencies such as the Department of War.

Existing Prohibitions on Chinese Tech Procurement

Numerous restrictions exist to prevent the procurement of Chinese technologies by the United States Federal Government (USG). These restrictions have been created and applied primarily by riders attached to funding vehicles such as the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which funds the Department of War and intelligence services.

The list below attempts to summarize the USG’s efforts to restrict the use of Chinese technologies by the government. In chronological order, Congress and the President have passed or signed the following:

- The Trade Agreements Act of 1979, which generally prohibits the purchasing of items for government use from countries that are not designated in the legislation, do not have trade agreements with the United States, or are not members of the World Trade Organization’s Government Procurement Agreement (WTO GPA) (General Services Administration, n.d.).

- The Entity List, maintained by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) in the Department of Commerce and created in 1997, which generally restricts exports of items to companies that, if exported, could run contrary to the national security interests of the United States (Bureau of Industry and Security, n.d.-a).

- The 1999 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1237, which authorizes the President to use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) against military companies of the People’s Republic of China operating in the United States (Public Law 105-261, p. 242).

- The 2006 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1211, which prohibits the purchase of items on the U.S. Munitions List (USML) or 600 series of the Commerce Control List (CCL) from companies “from any Communist Chinese military company” (22 C.F.R. § 121.0; Bureau of Industry and Security, n.d.-b).

- The 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1656, which prohibits the use of telecommunications equipment manufactured in the People’s Republic of China for any purposes related to the command, control, and communications system of the nuclear arsenal of the United States (Public Law 115-91, p. 479).

- The SECURE Technology Act of 2018, which created the Federal Acquisition Security Council at the Department of Homeland Security, empowers the council to coordinate with agency heads to issue exclusion and removal orders for equipment and vendors that may present in their systems and which present security risks (Public Law 115-390).

- The 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 889, which prohibits the purchase of “telecommunications equipment or services as a substantial or essential component of any system” from the PRC (Public Law 115-232, p. 282).

- Executive Order 13873, signed by President Trump in May of 2019, which prohibited the acquisition of most telecommunications and information technology services produced by “adversary countries” (84 FR 22689).

- The Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act of 2019, which restricts all recipients of FCC funds and federal agencies from purchasing items on a “covered list” created by statute, with the companies listed at the FCC Commissioner’s determination; the current list includes primarily Chinese telecommunications and digital product companies (Public Law 116-124; Federal Communications Commission, n.d.).

- The Secure Equipment Act of 2021, which expanded upon the Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act of 2019 by empowering the FCC to deny companies on the covered list (primarily Huawei and ZTE) the ability to be reviewed by the FCC, causing a de facto ban on their use in the United States (Public Law 117-55).

- The 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 841, which prohibits the Department of Defense from procuring printed circuit boards from covered nations, which includes the People’s Republic of China (Public Law 116-283, p. 377).

- The 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1260H, which establishes a public list that the Department of War must maintain, cataloguing Chinese military companies that operate or sell products into the United States (Public Law 116-283, p. 579).

- The 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 5949, which prohibits a wide range of Chinese semiconductor products from procurement by federal agencies, primarily targeting state-backed semiconductor corporations such as SMIC, and any other entities as determined by the Secretaries of Defense or Commerce (Public Law 117-263, p. 1098).

- The 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act (Omnibus), Division R, Section 101, prohibited the downloading and use of TikTok or other similar ByteDance applications on government devices, except for law enforcement use cases (Public Law 117-328, pp. 800-801).

- The 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 154, which prohibits the Department of War from procuring batteries from several named Chinese battery companies, most prominently CATL and BYD (Public Law 118-31, p. 47).

- The 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 805, which prohibits the Department of War from entering into contracts or procuring goods from companies on the 1260H list, established by the 2021 NDAA, which lists Chinese military companies. This section, however, exempts “components” as defined in U.S. code (Public Law 118-31, p. 181).

- The 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1823, which prohibits agencies from procuring “unmanned aerial systems” (primarily drones) from any manufacturers that are “subject to influence or control” by the PRC or CCP (Public Law 118-31, p. 558).

- The 2025 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 164, which prohibits the Department of War from procuring LiDAR or ranging technology from China and other adversarial countries (Public Law 118-159, p. 46).

- The 2025 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 4663, which prohibits the Department of War from contracting with companies that lobby on behalf of any 1260H list companies (Public Law 118-159, p. 223).

In addition to the above, several ad hoc measures are ongoing, with powers being exercised by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to prevent the import of items manufactured in China. A prominent example of this practice is the CBP preventing the importation of DJI drones suspected of being manufactured with forced labor, in violation of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) (DJI, 2025).

Regulatory and Oversight Bodies for USG Procurement

The United States Federal Government has several agencies and other administrative bodies governing the procurement of and standards for items purchased by government organizations. These procurement programs vary in their structure, in their reliance on career versus political staff, and in their collaboration with other standard-setting and acquisition bodies of the federal government.

The Department of War has a complex web of various officials, councils, and offices responsible for procurement and standards, particularly for technologically advanced items. Most of these are overseen by either the Under Secretary of War for Acquisition and Sustainment (USW(A&S)) and their constituent assistant secretaries and councils, which include political appointees, or the Chief Information Officer (CIO) of the Department of War, also a political appointee, who specifically oversees digital technology acquisitions.

In contrast, the Department of Homeland Security's procurement operation is mainly reliant on one political appointee – the Under Secretary for Management (USM) – and a team of career staff, typically members of the Senior Executive Service (SES). This model of procurement management is far more common in the federal government.

Government-wide, several bodies exist that institute standards and set policies for procurement, with which agencies collaborate on varying bases.

The Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) is located within the Office of Management and Budget in the Executive Office of the President. It is principally responsible for managing the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), a set of high-level policies that govern procurement throughout the entire federal government.

The General Services Administration (GSA) establishes practical, numerical standards for government procurement and serves as the primary purchaser for multi-agency procurement contracts. It sets most of these standards through voluntary adoption and is primarily focused on cost savings and efficiency, rather than being singularly concerned with security or scientific concerns.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a technical agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce, primarily concerned with standards and best practices related to cybersecurity, science, and engineering. It is only a standard-setting body and makes no binding acquisition policies or purchases on behalf of other parts of the government.

These agencies inform multiple steps of government procurement, sometimes contradicting or complementing the decisions of other acquisition offices within separate agencies, creating a complex web of standards for USG procurement.

The Pentagon’s Reliance on Chinese Products

The Department of War, aware of the growing threat from the People’s Republic of China and its prevalence in global supply chains, has commissioned several reports from outside groups to assess its acquisition of Chinese products. Their findings are troubling.

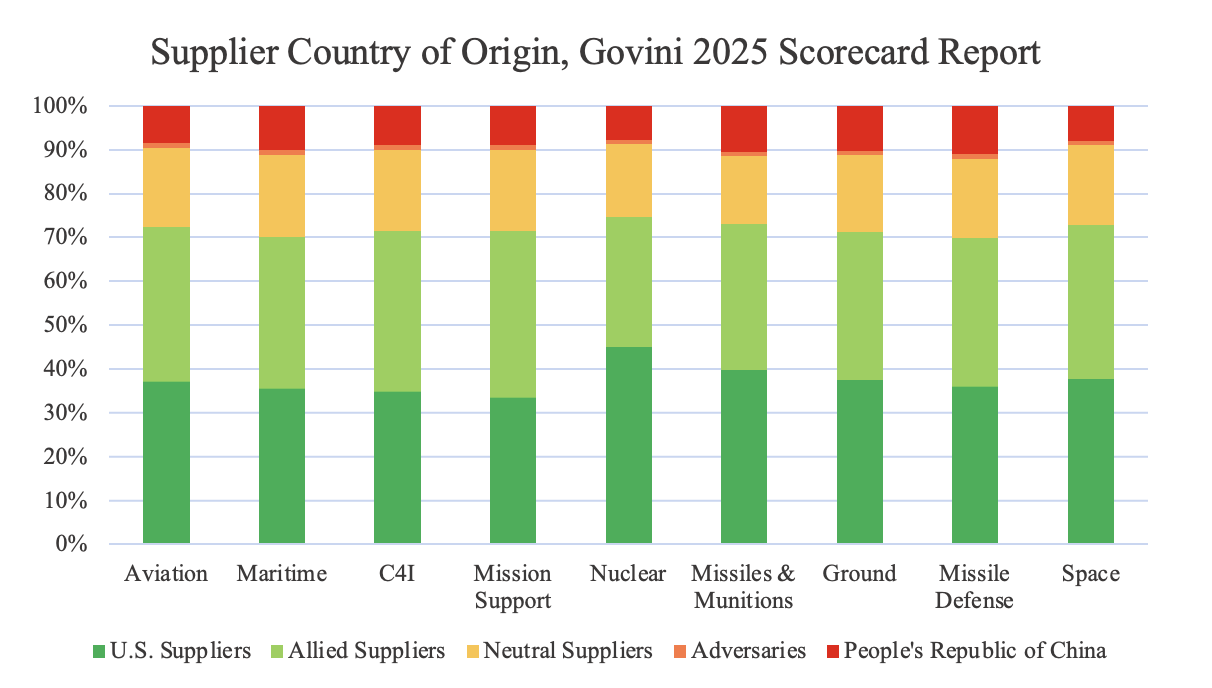

A 2025 analysis by the defense software firm Govini found that in FY24, China was still present in numerous areas of procurement in the Pentagon. Setting aside its dominance in critical minerals—which by itself poses a significant risk—Chinese-manufactured defense articles consistently comprise approximately 10% of all items across various categories, as illustrated below.

Data reproduced from Govini’s 2025 National Security Scorecard. Sector supplier counts exclude prime vendors, as they are prohibited from being from adversarial countries, and subcontractors. This methodology was the same as that used by Govini in their press releases for their report.

These trends are only exacerbated by the growing, rather than shrinking, reliance upon Chinese suppliers in some sectors of procurement. Govini’s data shows that in the aviation, maritime, C4I (command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence), nuclear, missiles, and missile defense sectors, Chinese products constituted a greater share of all foreign suppliers procured by the USG compared to 2024 (Govini, 2025).

This analysis is also alarming, given that the 2024 analysis reported an even higher rate of increase in the use of Chinese technology by the Department of the Air Force and miscellaneous Department of War offices, at 68.8% and 38.2%, respectively (Govini, 2024)[1].

Analysis by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) is similarly negative. GAO identified numerous structural flaws in the Department of War’s procurement and contract identification process. In one example, out of 115 suppliers for contracts related to the F-35, 114 are identified as simply being from the United States, even though each of these suppliers has hundreds of its own suppliers, which are not similarly investigated. This results in incidents such as Lockheed Martin informing the DoW, after their manufacture, that magnets used in some F-35s were manufactured in China (Government Accountability Office, 2025, pp. 8-9).

GAO identified similar flaws in other procurements. Among microelectronics used in DoW systems, 88% are estimated to originate from overseas, primarily in Taiwan, South Korea, and China (Government Accountability Office, 2025, p. 9). Though efforts have been taken by Department of War procurement offices to illuminate parts of these processes, the systems developed for this purpose have yet to “[be] used to proactively identify and mitigate foreign dependency risks” as of July 2025 (Government Accountability Office, 2025, p. 11).

The Department of War has attempted to address supply chain risks posed by China since the early 2000s. However, none of these efforts have comprehensively solved national security concerns, nor have any solutions been centralized for the entire Department. Much of the current delay since the beginning of the new Trump Administration (according to GAO) is due to disagreement over DoW officials “not [identifying] resources, priorities, and time frames for the [new office for supply chain risk] to complete relevant actions” (Government Accountability Office, 2025, p. 16).

Additionally, some suppliers are uncooperative with USG oversight. The GAO noted that some companies refuse to cooperate with probes into their reliance on foreign suppliers, with the companies arguing that such cooperation is not required in their contracts with the DoW (Government Accountability Office, 2025, p. 17). DoW officials also informed the GAO that they have reason to believe the suppliers already have this information available, and requesting it would not significantly increase costs (Government Accountability Office, 2025, p. 18).

This issue grows far more concerning when combined with the recent weaponization of rare earths, magnets, and other mineral export restrictions that the People’s Republic of China has placed on the United States. Since the announcement of reciprocal tariffs by President Trump in April 2025, China has repeatedly applied pressure by restricting exports of resources it has overwhelming market control of (Ministry of Commerce, 2025; Emont, 2025; Emont et al., 2025).

The list of rare earth materials and technologies that have faced export controls, licenses, or similar barriers to purchase from the PRC has steadily grown since 2023 (Shivaprasad et al., 2025). Below is a basic table outlining the development of these export restrictions. Note that additional restrictions were announced during April of 2025, mainly as retaliation for President Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs.

PRC Export Controls of Minerals & Technology Since 2023

2023 |

2024 |

2025 (pre-April) |

2025 (post-April) |

Rare Earth Technologies |

End Use Reporting Requirements |

Lithium & Gallium Technologies |

Rare Earth Magnets |

Graphite |

Gallium, Germanium, and Antimony |

Tungsten, Indium, Bismuth, Tellurium, and Molybdenum |

Samarium, Gadolinium, Terbium, Dysprosium, Lutetium, Scandium, Yttrium |

Rare earths restrictions are also done under the guise of licensing or reporting requirements in addition to the minerals themselves, as opposed to more confrontational restrictions placed on finished products. These sorts of restrictions demonstrate that the PRC understands that its leverage comes from the extraction and refinement of such materials, rather than its finished products. This strategy succeeded when rare earth magnets and other materials were used as bargaining chips in tariff negotiations with the United States this year.

Most of the materials that the PRC has restricted since 2023 are noted in Govini’s analyses as being frequently used in military items. Graphite, gallium, germanium, and tellurium are each used in hundreds of systems across nine categories listed in their report.

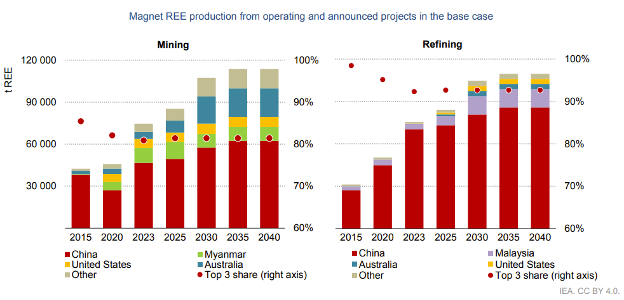

China’s predominance in refinement enables it to control what is otherwise a global supply of rare earth materials. While other countries may compete in the extraction and mining of such materials, China remains the preeminent refiner and processor of these compounds. This pattern holds for rare earth elements, rare earth magnets, graphite, and lithium.

Graph reproduced from the International Energy Agency’s 2024 Global Critical Minerals Outlook. Note that, in the case of rare earth magnets, China is the single largest extractor and refiner of rare earth magnets. This pattern is the case for many rare earth and otherwise critical mineral materials that are used in the Defense industry.

China’s control over defense product manufacturing is a consequence of its dominant role in refining the resources used in such products. Combined with excess industrial capacity capable of meeting demand, future defense procurements will inevitably face the risk of supply chains connected to the PRC.

Attempting to “de-risk” or migrate these supply chains entirely towards allies, however, provides mixed results. The Federal Reserve Board of Governors found that major U.S. trade partners increased their imports from China as the United States decreased its imports from China (Hoang & Lewis, 2024). Domestic mandates to reduce reliance on Chinese manufacturing will achieve little unless the alternatives are also proven not to have a dependence on Chinese suppliers.

Pentagon Contractors Knowingly Outsourcing Components and Technical Information to The People’s Republic of China

Defense contractors themselves are partly responsible for the Pentagon’s reliance on the PRC. The allure of cheap manufacturing is a strong enough economic incentive that many defense contractors either rule out or ignore the possibility of “decoupling” entirely from the PRC or choose to continue relying on Chinese suppliers or subsidiaries (Pfeifer, 2023; Hepher & Shephardson, 2024). In fact. many American companies, including some defense firms, claim that efforts to decouple from China are impossible. The primary contrasting example, as noted by Raytheon’s CEO, was the ability of American companies to decouple from Russia in the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine. The extent of industrial connections to China, however, is too much to undo, according to Raytheon and many other firms (Pfeifer, 2023; Obialo, 2024).

The unfortunate reality is that many of the world’s manufacturers, once they began moving manufacturing of any kind to the People’s Republic of China, created a “agglomeration effect” or “cluster effect” of suppliers for their operations in China. Even though the principal manufacturers may wish to decouple from China, the economic consequences of their original move will be hard to undo. This is best observed in places like Shenzhen, which was once a “small fishing village of 30,000 before it was designated as one of the first [Special Economic Zones] in 1980 […] is [now] considered by some to be ‘China’s Silicon Valley’” (Obialo, 2024). Numerous studies by economists have identified the incredibly tight correlation between the agglomeration effect (often explicitly guided, encouraged, or outright enforced by government subsidies and penalties) and increased industrial productivity (Lu et al., 2019; Xi et al., 2021; Grover et al., 2021; Li et al., 2025).

Major defense prime contractors have exported controlled technologies or design information to numerous adversaries, including the People’s Republic of China. Over the past four years, many of these contractors have agreed to settlements with the USG. The Department of State, as the principal enforcer of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), issues penalties for violations of export controls related to weapons systems.

Instances of defense contractors violating these restrictions include (Department of State, n.d.):

- Honeywell International, Inc. settled with the Department of State over the transmission of classified or otherwise restricted engineering drawings of parts (primarily engines and electronics) for the F-35, F-22, C-130, Apache Helicopter, and Abrams Tank, among other equipment, to Canada, Ireland, the PRC, and Taiwan, presumably for technical design or manufacturing purposes.

- Boeing settled with the Department of State after admitting to exporting, through transmission of files to foreign employees working in the PRC, data related to the F-18, F-15, F-22, E-3, and AH-64 aircraft, in addition to data on the AGM-84E and AGM-131 missiles. It is not stated in the filing why such data was made available in the first place. Similar violations occurred with data transmitted to Russia and Singapore. Boeing was also accused of having subsidiaries forge export licenses.

- Raytheon Corporation (RTX) settled with the Department of State after admitting, only after a significant delay, that it allowed for data for practically every aircraft[2] that it or its subsidiaries manufactured or worked on to be transmitted to the PRC so that PRC-based manufacturers could produce electronic components for the aircraft. Similar unauthorized exports of parts or data to countries such as Singapore, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and Turkey also took place for separate products, including numerous modern missile designs.

Many of these violations had been ongoing for years, with occasional voluntary disclosures from the corporations involved. Penalties are primarily limited to civil fines and consent agreements designed for prevention; in Raytheon’s case, it was required to pay $200 million in fines.

It is unclear whether the above instances of reliance on PRC suppliers would have been counted or evaluated in Govini’s research data mentioned in the previous section. It is also unclear whether Govini would have assessed some of these instances (such as overseas subsidiaries of companies such as Boeing, Lockheed, or Raytheon) as being “Chinese” products or not.

Case Study: Encryption Devices and “Bridge Chips” Procured from China

The ever-present threat of Chinese corporation-state cooperation (sometimes referred to as civil-military fusion) creates risk wherever sensitive industries procure even the simplest Chinese components. This cooperation, mandated under China’s National Intelligence Law of 2017, poses a risk that any Chinese products may be compromised in a way that could either relay proprietary data or act as a remote termination switch; as mentioned above, there exists practically no boundaries on what could be expected of Chinese citizens under the law (China Law Translate, 2017). For example, just this year, communication devices were discovered in Chinese-manufactured solar panels sold to customers in the United States (Macfarlane, 2025).

The Department of War also procured devices with compromised components that were manufactured in China. The Bureau of Industry and Security within the Department of Commerce maintains the Entity List, which primarily serves as an export control/prevention registry, specifically to restrict the export of national security-sensitive items to companies or overseas organizations. However, some entities on the list may also manufacture components or products themselves. Unfortunately, the Department of War has knowingly (at least since 2023) been procuring devices manufactured by companies that have been placed on the Entity List by the Commerce Department.

In a letter dated October 5, 2023, Rep. Austin Scott of Georgia wrote to the Department of War to ask if systems produced by Hualan Microelectronics, Sage Microelectronics, and Initio—the first two being explicitly named in the Entity List, and the latter being a Taiwan-based subsidiary—were used by the Department. Hualan and Sage were invited to a CCP-run science and technology award ceremony to recognize their innovations, and they were personally acknowledged by Xi Jinping (Sage Microelectronics, 2021). Two months later, on December 6, 2023, the Chief Information Officer of the Department of War replied, stating that because the Department of War was not prohibited from purchasing devices with the components of those companies, and because the DoW lacked a Bill of Material itemizing components, “DoD [would] continue to assess overall supplier and technology risks and apply a variety of risk management tools,” (Scott, 2023).

Companies that integrate such devices include Apricorn (Apricorn, n.d.), SecureData (Greenberg, 2023), and iStorage (Skorobogatov, 2021, pp. 35-37), all of which utilize Initio components in their devices and routinely compete for government procurement contracts. Engineered vulnerabilities that may have been created would be “impossible to detect,” and could lie dormant through close analysis until their activation (Greenberg, 2023). These devices are certified for use by NIST under a standard known as FIPS-140. Unfortunately, the use of components manufactured by companies domiciled in a foreign adversary does not affect NIST’s certification of such devices. Nevertheless, continued certification is then used by agencies such as DoW as the reason for their purchase of these items.

Subsidiaries should not be excluded from the Entity List and should, by default, also be prohibited. Unfortunately, procurement continues apace.

Case Study: Lenovo Controlled by PRC Investors, Procurement Continues

Restrictions on PRC products are not exclusively a new creation or policy measure. Such restrictions are the consequence of long-standing problems that the USG has had with such products.

For example, Lenovo’s ownership structure and products themselves have created numerous national security concerns. Lenovo is primarily known for its ThinkPad line of laptops, which it purchased from IBM in 2005 (Hamm et al., 2004). Lenovo’s single largest shareholder is Legend Holdings, which serves as the investment holdings arm of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, China’s national science academy (Osawa & Luk, 2014). Legend Holdings and its associated individual investors continue to own approximately one-third of all Lenovo shares as of the end of 2024 (Lenovo Group, 2025).

Lenovo devices have a long history of compromised security and backdoors when used by the US government. In a 2008 lawsuit, it was alleged that devices were relabeled in violation of procurement regulations, given to the United States Marine Corps, and transmitted most, if not all, of the data on the laptops back to China (Chieffalo, 2010, pp. 71-73). This came after the State Department banned Lenovo devices from its network in 2006 for unclear reasons, whether due to ownership or incident-related concerns (Gross, 2006).

Concerns persisted into the 2010s, with Lenovo’s installation of software from an Israeli-based firm on all its devices, which rerouted all web traffic through the firm’s servers (Weise, 2017). However, the firm closed shortly after Lenovo began implementing the program on devices, effectively allowing all web traffic from all devices to be scanned by whoever controlled the servers (Federal Trade Commission, 2017). Lenovo was also among many companies to have some of its products banned from import into the United States due to violations of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in 2020 (Kwan, 2020).

These concerns alone have generated what amounts to only an informal ban on Lenovo devices in limited parts of the USG: although other companies, such as Huawei and ZTE, face formal bans on procurement through the FAR framework, Lenovo does not (Federal Acquisition Regulation, 2025). Instead, numerous agencies, including the Department of War, have issued reports detailing countless cybersecurity vulnerabilities. The Inspector General of the Department of War specifically alleged that purchases were made with known cybersecurity risks; these risks are unknown to the public, and their details remain classified (Department of Defense Inspector General, 2019).

The purchase of Lenovo goods continues, primarily through technology service providers. Despite numerous cautions from the Inspector General’s office and the Joint Staff, the Pentagon continues to purchase these devices (Nicholas, 2016). The DoW, spent millions procuring Lenovo’s devices, with some purchases already having taken place in FY25 by the Department of the Army, specifically $154,880, for “the purchase of 8 Lenovo high-performance workstations” (USASpending, 2025).

Case Study: Microsoft’s “Digital Escort” Program for the DoW

Separately from the purchase of vulnerable items manufactured or compromised by the People’s Republic of China is the issue of digital access, cybersecurity, and the use of foreign nationals for digital services.

Beginning in 2011, with the beginning of the USG’s Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FEDRAMP), standards for companies that provided cloud or other digital services had a high bar to clear: people providing technical support for classified systems would be required to have the same level of clearance as those permitted to use them for the USG (Dudley & Burke, 2025). Microsoft, with its heavy reliance on its workforce in India, China, and elsewhere, was concerned it would find itself ineligible for many government contracts, so it engaged in a lobbying campaign to ease these requirements. Microsoft successfully lobbied for a digital version of NIST’s recommendations for supervising maintenance technicians in classified environments when the technicians lack clearances themselves – as one former Microsoft executive was quoted, it allowed the company to “go to market faster” (Dudley & Burke, 2025a).Dudley & Burke, 2025a).

When Microsoft received full authorization for FEDRAMP in 2016, the program went into full force (Microsoft, 2016). The program, as described by Renee Dudley and Doris Burke for ProPublica, is woefully inadequate, and its implementation defies explanation:

Here’s an example of how it works and the risk it poses: Tech support is needed on a Microsoft cloud product. A Microsoft engineer in China files an online “ticket” to take on the work. A U.S.-based escort [usually only needing a security clearance, not technical expertise to supervise the work, and who may be paid as little as $18/hr] picks up the ticket. The engineer and the escort meet on the Microsoft Teams conferencing platform. The engineer sends computer commands to the U.S. escort, presenting an opportunity to insert malicious code. The escort, who may not have advanced technical expertise, inputs the commands into the federal cloud system. (Dudley & Burke, 2025a)

Similar programs are employed at other federal agencies, such as the Departments of Justice, Treasury, and Commerce, where digitally escorted engineers have been approved to work on systems “where the loss of confidentiality, integrity, and availability would result in serious adverse effect on an agency’s operations, assets, or individuals” (Dudley & Burke, 2025b).

It was also reported that Microsoft did not disclose to the DoW that the digital escorts who were used in the program were not necessarily Microsoft employees but may have been screened for suitability by a third-party staffing company with far less expertise (Dudley & Burke, 2025c). The details of the digital escort program itself were so obscure at the Pentagon that a Defense Information Systems Agency spokesperson was quoted as saying that “[l]iterally no one seems to know anything about this, so I don’t know where to go from here” (Dudley & Burke, 2025a).

Following ProPublica’s revelation of the Microsoft system, the Department of War suspended the program and sent a letter of concern to Microsoft, which also made changes, including ending the use of Chinese engineers for similar programs; however, the Pentagon left open the possibility of other foreign nationals working on sensitive systems through the digital escort model (Dudley, 2025).

This “digital escort” incident raises questions about Microsoft’s other services provided to the government. This security flaw is not the first involving Microsoft’s services to the USG, an area in which several of their practices have caused myriad failures. A 2024 CISA review of a 2023 breach of Microsoft’s Exchange Online program, a hack that compromised the accounts of the Secretary of Commerce, U.S. Ambassador to China, and Representative Don Bacon (R-NE-2), found that the breach was enabled by:

[T]he cascade of Microsoft’s avoidable errors […] If Microsoft had not paused manual rotation of [security] keys; if it had completed the migration of its [Microsoft Account] environment to rotate keys automatically; if it had put in place a technical or other control to generate alerts for aging keys […] If Microsoft had deployed alerting or prevention to detect forged tokens that do not conform to Microsoft’s own token generation algorithms. (Cyber Safety Review Board, 2024, p. 17)

The security failures of Microsoft’s services to the USG should cause alarm, especially due to its delayed admission of security compromises. Many of these failures emerged after changes were made in the wake of a system outage Microsoft had suffered in 2016 (Cyber Safety Review Board, 2024, pp. 15-19).

Failures in Procurement Vetting in Civilian Agencies

Civilian agencies are just as likely to procure Chinese technologies and products, both knowingly and unknowingly. Though many agencies are principally responsible for their own purchases, the General Services Administration (GSA) is responsible for multi-award schedule (MAS) contracts. These contracts set pre-arranged prices and specifications for large-quantity, low-to-moderate complexity items. The GSA, in effect, serves as a first-line evaluator for items and has several prohibitions on the purchase of items that Congress previously restricted, such as Chinese-manufactured Huawei or ZTE telecommunications equipment.

Despite this prohibition, on multiple occasions, both the GSA and individual agencies have mistakenly violated these principles or been deceived into purchasing restricted equipment through relabeling. On at least two occasions since 2022, the GSA discovered multiple contracts related to telecommunications hardware in which providers were routinely purchasing prohibited equipment and selling it to government purchasers (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2023, p. 7). These same products, when delisted, were then relisted on GSA’s procurement platform under different part numbers, evading software specifically designed to catch such efforts due to changes to “the manufacturer name, part number[,] or unit of issue” (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2023, p. 9).

The processes to remove these parts, the Inspector General noted, encounter “lengthy delays [up to] four times as long” as the removal timeline requirement stipulated in contracts with the GSA (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2023, p. 10). Furthermore, contractors who failed to de-list items or repeatedly violated other procurement protocols were not adequately punished, and some who were warned declined to take any action, continuing to list the items at issue (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2023, p. 11). Structurally, the IG identified a lack of capacity to notify agencies when items they have previously purchased are non-compliant, and they found that GSA took over two years to begin complying with requirements to identify and restrict prohibited subcontractors who provided services to suppliers (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2023, pp. 11-12). The companies whose items were sold under this oversight included Huawei, ZTE, and Kaspersky Lab.

Similar failures have occurred at the executive level of the GSA, with the GSA’s Chief Information Officer having signed off on the purchase of over 150 Chinese-manufactured teleconference cameras, because staff claimed that no non-Chinese-made alternatives existed (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2024, pp. 2-5). Upon later analysis by an outside cybersecurity firm, these exact cameras were found to be capable of functioning as “rogue wireless network gateways” that could be used to gain illicit access to any network to which they were connected. As of the IG’s 2024 report, 36% of the cameras had not received a software update that prevented this exploit (General Services Administration Inspector General, 2024, pp. 2-7).

Separate incidents have occurred with other civilian agencies. For instance, the United States Secret Service (USSS) purchased at least 10 DJI drones in 2021 through a government contract; however, it was unclear why DJI, a Chinese company, was chosen as the vendor (Schönander, 2023b). Another batch of DJI drones was purchased by the USSS in 2022 (Schönander, 2023b). Through law enforcement grant and assistance programs administered by DHS, local and state law enforcement agencies also purchased DJI drones with grant money provided by the department (Schönander, 2023a). Internal warnings cautioning against the use of DJI drones by contractors in their construction of federal facilities – including those for DHS – were issued in 2017, but purchases continued by the agencies themselves (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2017).

Consulting services with the Department of War and the Department of Homeland Security collectively account for over 50% of the government’s total consulting purchases (Government Accountability Office, 2024, p. 1). A 2024 GAO report noted that these two agencies had few, if any, safeguards to verify that the consulting services they hired were not contracting with the PRC. Section 847 of the 2020 NDAA, the Preventing Organizational Conflicts of Interest in Federal Acquisitions Act, and section 812 of the 2024 NDAA—laws passed to address these risks—are yet to see fruition, as the statutory deadlines to implement them have been missed (Government Accountability Office, 2024, p. 10).

Much of the impetus to prevent such procurement mistakes originates in Congress. However, without proper implementation in agencies, as required by the laws themselves, the legislation can have zero effect.

Conclusion

Government procurement is a lengthy, complex, and expensive process. There are bound to be failures in procurement protocol by government agencies that inadvertently purchase prohibited goods, such as those from the People’s Republic of China. Nevertheless, government agencies responsible for setting and establishing technical requirements should provide a first layer of defense. Individual agency purchases are also liable for screening their procured goods for compromised parts.

Despite repeated attempts by Congress to set limits on the ability of agencies to purchase such goods, the proliferation of waiver authorities in these restrictions has led to a lack of seriousness. Agencies have attempted to comply with requests from Congress by establishing their own internal standards; however, a constrained market of alternative goods makes future failures possible.

The process by which procurement is first screened or outlined by the General Services Administration presents an opportunity to strengthen procurement procedures; however, other agencies must also institute reform. When agencies must purchase goods for which no non-PRC-manufactured alternatives exist, their procedures must ensure that the risks associated with purchasing such goods are appropriately evaluated and mitigated.

These risks are particularly amplified in the procurement decisions of America’s two most sensitive cabinet agencies: the Department of War and the Department of Homeland Security.

The Department of War’s reliance on Chinese-produced rare earth materials and defense products is pervasive. Despite decades of attempts to reduce its reliance on adversarial supply chains, it still fails to disconnect itself, while simultaneously relying on numerous contractors with intricate ties to China and ongoing knowledge transfers to Chinese subcontractors and subsidiaries.

At the Department of Homeland Security, sensitive bureaus and agencies under its supervision (such as the United States Secret Service) rely on Chinese-made electronics, such as drones. The agency responsible for the security of America’s most important officeholders, which purchases products from adversaries, must be examined, and reforms must be implemented to prevent further purchases.

In the short term, decoupling entirely from such supply chains will likely prove more expensive than the alternative. If national security is to remain the top priority, however, these costs will have to be absorbed. Continuing to purchase such goods, especially for the Departments of War and Homeland Security, runs counter to the intent of Congress and the now-improved understanding of every element of the threat that the CCP poses to the United States.

Policy Recommendations

We recommend the following policy changes:

- OMB: The Office of Management and Budget should, pursuant to Government Accountability Office reports, implement the following:

- Per the GAO’s recommendations, the Administrator of OFPP should expedite the synchronization of procurement restrictions of items produced by companies on numerous lists produced by several departments, including Commerce’s Entity List, War’s 1260H list, and service providers who actively consult for or otherwise work with the People’s Republic of China, and;

- Do such work in conjunction with the Federal Acquisition Security Council, and;

- Due to PRC laws, including, but not limited to China’s 2015 National Security Law and 2017 National Intelligence Law that give the Chinese government sweeping authorities to compel PRC-based companies to cooperate with China’s defense and intelligence agencies, OMB should issue a government-wide ban on procurement from Chinese-owned companies and their subsidiaries who are subjected to these laws, and whose hardware or systems could contain or transmit USG data.

- GSA: The General Services Administration (GSA) should, pursuant to Government Accountability Office and Inspector General reports, implement the following:

- a. Per the IG’s recommendations, ensure that GSA employees no longer approve TAA (Trade Adjustment Act) noncompliant purchases in instances where alternate products meet requirements, and;

- b. Per the IG’s recommendations, increase oversight of its technology employees to address misleading information being provided to senior employees for the approval of purchases.

- NIST: The National Institute of Standards and Technology should do the following:

- Officially warn vendors using sensitive components manufactured by companies subject to the laws of hostile nations that the government is aware of the use of their components and begin the process of evaluating their security to the maximum extent possible. While no current removal authority exists for NIST to de-certify based on the manufacturer’s usage, investigations should begin as soon as possible to ascertain if the devices themselves have any vulnerabilities, and;

- Promulgate through publications such as NIST’s Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management (C-SCRM) warnings about the integration of risky, Chinese-made components into sensitive technologies, such as those governed by general ICTS regulations, or those governed by NIST encryption standards.

- DOW: The Department of War should, pursuant to Government Accountability Office and outside consultations, implement the following:

- Stand up the Supply Chain Risk Management Integration Center to coordinate procurement risks in supply chains for DoW procurement, and;

- Assign responsibility for DoW to implement standard private practices for awareness of supply chain dependencies, and;

- Attempt to maximize the country-of-origin information for all articles procured and contractors hired for DoW purposes, and implement standard contract language that obligates contractors and suppliers to cooperate with such efforts.

- DHS: The Department of Homeland Security should, as the home of the Federal Acquisition Security Council and regarding its own agency activity, implement the following:

- Issue, as much as possible, removal and exclusion orders that would address the proliferation of compromised devices in other agencies, and;

- Limit procurement of Chinese devices from within its own agencies and offices wherever possible, and;

- Ensure suspected UFLPA violations are investigated in a timely manner and all subsidiaries of a company on the UFLPA Entity List – and any Chinese company with components provided by a company on the Entity List – are automatically added to the Entity List.

- Congress: The Congress should:

- Pass general, guiding language regarding procurement that specifies, in no uncertain terms, that procurement is to avoid, as much as possible, named companies and countries that have been identified as hostile to the interests of the United States. Procurement law must be strengthened at both the multi-agency (GSA) and single-agency levels to require verification of purchases of Chinese goods, ensuring that all other options are exhausted, and waivers should no longer be added to the statute without reporting or other verification measures, and;

- Strengthen the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council (FARC) and Federal Acquisition Security Council (FASC).

Resources