Repealing Grocery Taxes to Ease Cost Pressures on Working Families

Key Takeaways

Amid the ongoing challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, grocery prices surged dramatically, adding significant strain to American households already burdened by decades-high inflation and the rising cost-of-living.

While the Trump Administration pursues trade re-negotiations and regulatory reforms to lower food prices, experts caution that global disruptions and unforeseen events drive prices higher.

By eliminating grocery taxes on essential food items, states could deliver immediate relief to families grappling with high prices on everyday necessities.

Introduction

As the nation emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Biden Administration’s massive spending surge in 2021 helped drive decades-high inflation, causing food prices to soar and burdening American families. In fact, this burden was especially noteworthy during the 2024 presidential election, after which President Donald Trump noted that the issue helped secure his victory. As he bluntly stated, “I won on the border, and I won on groceries” (Steinhauser, 2024).

Both poll numbers and the sheer increase in grocery prices since the beginning of the pandemic lend credence to Trump’s observation. Post-election analyses revealed that controlling inflation was the highest priority for some 40% of voters and, of these, Trump won a 2-1 advantage over Kamala Harris, the candidate running on continuity with the Biden Administration’s post-COVID-19 policies (Fox News Polling Unit, 2024). These voters’ concerns are not imagined, especially when it comes to food prices. While inflation across all Consumer Price Index (CPI) categories between March 2020 and March 2024 measured 20.3%, prices in the “food at home” category increased 24.7% during the same period (Fontanella, 2024).

While the Trump Administration has made strides on deregulation, renegotiated trade agreements, and addressed global disruptions (such as the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) that spiked egg prices during the last year), many Americans continue to express concern over higher food prices.

However, there is hope. States can provide immediate relief to working families struggling with grocery bills by repealing state sales taxes on groceries. The idea has gained bipartisan support, as more than half a dozen states have either repealed or are seriously considering proposals to eliminate grocery taxes. States with diverse political persuasions have eliminated their grocery taxes in the last two years, such as Illinois, where the state government is dominated by Democrats, and Arkansas, where the state government has Republican supermajorities.

The rationale cited in both states was that the post-COVID-19 rise in grocery prices was burdensome. In Arkansas, Governor Sarah Sanders decried the post-COVID-19 “reckless tax-and-spend policies…[for] driving food prices through the roof” (Arkansas Governor’s Office, 2025). In fact, while Illinois’s repeal was initially temporary for Fiscal Year 2023, its savings proved popular amidst persistently high grocery prices, saving taxpayers some $360 million during that year (Sharkey & Josko, 2023). Polls indicate that, at the same time, 70% of state voters approved a permanent repeal (Sharkey & Josko, 2023). Indeed, the state permanently eliminated its grocery tax in 2024 (Karg & Sharkey, 2024).

Opponents have raised strong objections, arguing that eliminating grocery taxes creates special carve-outs for the food industry and deprives state and local governments of critical revenue. However, unlike other consumption taxes—where buyers can choose whether to spend—no family can opt out of purchasing the staples of life: nourishing food and essential ingredients. In states such as Illinois that have repealed grocery taxes, the impact has been both tangible and immediate. Amidst soaring grocery prices post-COVID, these grocery tax repeals have proven to be overwhelmingly popular—a strong indication that citizens appreciated the measurable reduction of the burden that governments impose on everyday necessities. The remaining states maintaining grocery taxes should follow suit and eliminate them permanently.

The Heavy Burden of Post-COVID-19 Grocery Price Hikes

The initial three to four years following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were marked by staggering decades-high inflation, with all items measured by the CPI rising some 21.2% between 2020 and 2024 (Davidenko & Sweitzer, 2025). Experts attribute this inflation to a myriad of causes, but primarily to pandemic-related stimulus money, mostly in the 2021 Biden-era American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). ARPA diverted approximately $1.9 trillion in transfers to state and local governments for non-COVID-related programs, spurring unprecedented spending and government expansion at these

levels when it was already apparent that the pandemic’s worst macroeconomic effects had largely subsided (Maher, 2025). Additionally, widespread supply chain disruptions affected global commerce across nearly all products requiring transportation to reach consumers. These disruptions were worsened by a surge in demand, fueled by deficit-funded spending, for which the compromised supply chains were unable to accommodate.

During the same period between 2020-2024, the all-food CPI rose by a staggering 23.4%, which was 10.4% more than the all items-CPI noted above. In 2022 alone, food saw the highest year-over-year increase in more than four decades (Davidenko & Sweitzer, 2025). These increases are even more dramatic when compared to prices before the COVID-19 pandemic, as grocery prices were approximately 27% higher in July of 2024 than they were five years earlier in July of 2019 (Newman & Nassauer, 2024). While inflation has slowed in 2025, there is more work to be done on food prices. In addition to being influenced by the same spending patterns and global supply chain disruptions that affect the all-item CPI, food prices are especially vulnerable to regional factors. These include the prolonged war in Ukraine and outbreaks of animal-borne diseases, such as the HPAI. In fact, the price for a dozen eggs in the United States doubled between January of 2020 and May of 2025, from $2.02 to $4.00 per dozen (Stiles, 2025). Egg prices, in particular, drew an immediate and high-profile response at the start of the second Trump Administration. In February 2025, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins unveiled a comprehensive five-part strategy to combat avian influenza, stabilize supply, and boost egg production through expanded vaccine and therapeutic development (Rollins, 2025).

Another contributing factor to high food prices is the uncertainty in retail pricing following the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, consumer demand shifted toward more budget-friendly and even “customized” products that better aligned with their budgets. In response, retailers began more assertively employing pricing strategies such as dynamic pricing, which includes changing prices during specific times of the day (Stening, 2024). This practice was enabled by the adoption of electronic shelf labels, which retailers implemented to help protect their profit margins. In addition to higher labor costs, the price for raw materials also surged, meaning that even things like food packaging, which can comprise up to 10% of a product’s retail price, also contributed to food inflation (Peek, 2023).

While inflation for eggs and dairy products was particularly acute, it is noteworthy that food price inflation was not limited to these products, but, rather, is consistent amongst different types of essential food items like coffee, beef, flour, and tomatoes, among others. So, while the especially large surge in egg prices noted above was exaggerated in the last year due to the HPAI, egg prices were already up 54% between November of 2020 and March of 2024 (Beck, 2024). During the same 40-month period, milk increased 36%, cheese and butter increased 30%, and bakery products like bread and crackers increased about 28% (Beck, 2024).

For a fuller look at the price pressures between the beginning of the pandemic and the time of this writing, the table below shows the increased prices of basic food staples that Americans purchase at retail grocery stores in March of 2020 (when COVID-19 restrictions began) and January of 2025, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Note that because it does not include all food items in the all-food CPI, the percentage of increase is larger than the CPI itself during this period. If nothing else, this discrepancy underscores how significantly the index understates the true impact of food inflation on the food items most essential for American families.

Table 1

Price Increases of Basic Grocery Staples Between March 2020 and January 2025[1]

| Food Product | Price in January 2020 | Price in January 2025 | Percent Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacon | $5.26/pound | $6.98/pound | 32.7% |

| White Bread | $1.37/pound | $1.88/pound | 37.2% |

| Chicken | $1.40/pound | $2.06/pound | 47.1% |

| Coffee | $4.33/pound | $7.93/pound | 83.1% |

| Eggs | $2.02/dozen | $4.55/dozen | 125.3% |

| Flour | $0.42/pound | $0.56/pound | 33.3% |

| Ground Beef | $3.88/pound | $7.69/pound | 98.2% |

| Milk | $3.25/gallon | $4.02/gallon | 23.75% |

Note: Data from Stiles, 2025.

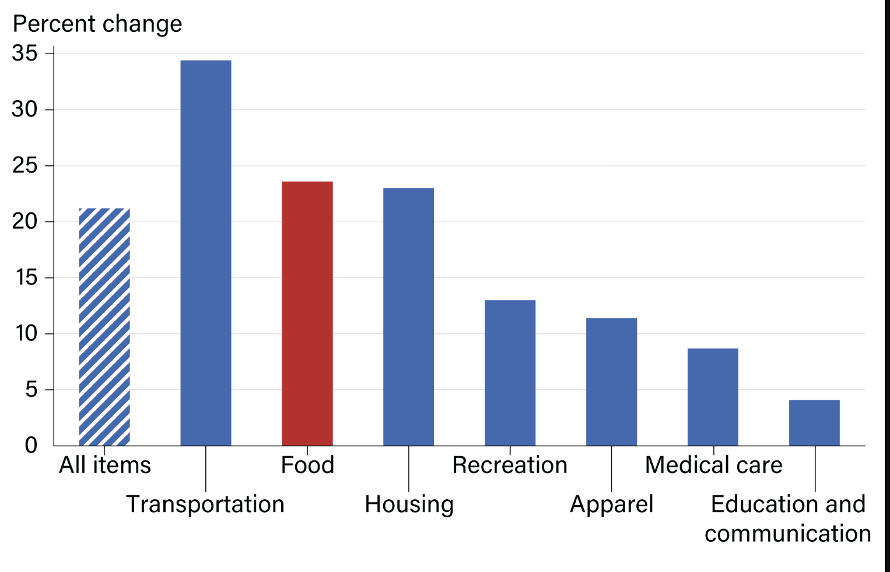

Relative to other categories, only the CPI for transportation exceeded the all-food CPI during the referenced time period among the major categories that index tracks (Davidenko & Sweitzer, 2025). Of course, it is worth noting that increased transportation costs include product logistics and delivery, which has a direct impact on the price of food. For reference, the chart below illustrates the increase in the all-food CPI compared to the all-items CPI and other major categories that the index measures.

Figure 1

Price Change for Major Consumer Price Index (CPI) Categories, 2020-24[2]

Note: Data from Davidenko & Sweitzer, 2025.

In an effort to compel other nations to renegotiate their trade postures towards the U.S. and reduce barriers to trade, President Trump is pursuing a necessary tariff and reciprocal tariff trade strategy. This strategy to reset our long-term trade equity could potentially have short-term implications on the price of certain staples, of which policymakers should try to mitigate at all costs.

No matter the precise causes of all-food inflation, the reality is that prices remain stubbornly high for what are arguably the least discretionary items the CPI tracks. For example, consumption related to the transportation CPI could be mitigated by using public transportation, carpooling, or telecommuting. Similarly, the next highest category (housing) could be mitigated by moving to less expensive locations or homes or sharing living spaces. Note that none of these situations are ideal, given that they cut to the heart of the necessities of daily life for tens of millions of working families and stand in contrast to the abundance and growth posture that Americans have come to expect in the macroeconomy. Still, these possible shifts in consumption highlight the inability to make changes beyond the margins when it comes to essential food items. Shifting to often less expensive, less nutritious options could lead to higher medical costs over the long term (Frey et al., 2025). When food costs rise, families often sacrifice other vital needs like healthcare, medication, or education. To ease these impossible choices, states should repeal grocery taxes to provide lasting relief that isn’t dependent on macroeconomic factors or uncontrollable events.

The Impact of Eliminating Grocery Taxes on American Households

Rising food prices have increasingly strained family budgets, as shown by the sharp growth in household food spending. In 2020, food comprised roughly 6.8% of a typical household budget. Yet, by 2023, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that the share nearly doubled to 12.9%, an increase of 89.7% (Sweitzer & Davidenko, 2024). The USDA reports that in 2025, a household of four (defined as two adults under 50 and two pre-adolescent children) can expect to spend between $997 and $1,603 per month on food, depending on purchasing habits and dietary preferences (Milam-Samuel, 2025). These figures represent a sharp increase compared to the USDA’s 2020 estimates, which projected monthly food costs for the same household to be between $591 and $1,154 (United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, 2020). Consistent with this trend, between 2020 and 2024, total food spending in the nation increased from $1.8 trillion to $2.6 trillion, a rise of 44.4% in just four years (Zeballos & Sinclair, 2025).

The effects of rising all-food CPI are broad and far-reaching, impacting both individual household budgets and aggregate consumer spending. Given the myriads of factors identified that may continue to drive food prices upward, there is a need for a swift, targeted, and easily implemented relief measure to mitigate the financial burden on households. Repealing state grocery taxes represents a practical and effective policy response.

Where Grocery Taxes Currently Stand

At present, the 11 states indicated in Table 2 impose sales taxes on groceries. A total of three states impose their full state tax rates on groceries, and eight impose reduced rates. Of these states, Arkansas and Illinois recently approved legislation that will fully repeal their state-level grocery taxes beginning January 1, 2026. The laws enacted in both states permit local jurisdictions to continue to impose grocery taxes. Note that classifications for what states consider items subject to the grocery tax vary, with certain states excluding sugar-sweetened beverages and candy from the definition of groceries, while others may not. In these cases, excluded items like soda would be subject to the full sales tax rate. Ultimately, every state in this category includes the food staples recognized by the USDA, many of which were noted in the section above. Below is a chart highlighting the 11 states that currently impose sales taxes on groceries (as each state defines the term):

Table 2

States Currently Levying Sales Tax on Grocery Purchases

| State | Grocery Tax Rate | Standard Sales Tax Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 3.000% | 4.000% |

| Arkansas | 0.125% | 6.500% |

| Hawaii | 4.000% | N/A |

| Idaho | 6.000% | N/A |

| Illinois | 1.000% | 6.250% |

| Mississippi | 5.000% | 7.000% |

| Missouri | 1.225% | 4.225% |

| South Dakota | 4.20% | N/A |

| Tennessee | 4.000% | 7.000% |

| Utah | 1.750% | 6.100% |

| Virginia | 1.000% | 5.300% |

Note: Data from Stripe, 2025; Walczak, 2025[4].

The impact of these grocery taxes on household budgets is staggering, especially when comparing the cost of groceries as a percentage of median monthly household income across all states. In fact, of the three states where grocery costs exceed 2.5% of median household income, two states (Arkansas and Tennessee) impose sales taxes on groceries. California, for example, has the nation’s highest state sales tax rate but exempts groceries, while Tennessee levies a 4.00% sales tax on groceries. At the same time, the percentage of monthly household income for groceries in Tennessee is 2.23%, while in California, the same share is 1.69% and ranks 40th among the states in this category—a difference of 39.15% (McCann, 2025). Naturally, these differences are affected by other factors such as logistics and supply issues. Still, it is manifestly clear that grocery taxes materially contribute to these disparities among the states. For example, Mississippi has the highest share of monthly household income spent on food at 2.64%, and also imposed the highest sales tax on groceries in the nation (7.00%), until this rate was lowered in July of 2025 (Walczak, 2025).

One counterargument to the disparity in the share of monthly household income spent on food is that many of these states also have the lowest median incomes, so essential expenses like food naturally comprise a larger proportion of a smaller income. Yet this reasoning underscores a key policy point in favor of repealing grocery taxes: they are inherently regressive. In other words, those with lower incomes pay a larger share of their earnings in grocery taxes, while those with higher incomes will pay a smaller percentage. Indeed, as noted in the previous section, the USDA outlines four tiers of average monthly food costs for a family of four, ranging from least to most expensive, labeled “low-cost” to “liberal,” in the Department’s terminology.

In June 2025, the gap between the USDA’s highest and lowest average monthly food cost tiers for a family of four (two adults 19-50 and two children 9-11 years old) is approximately $566 and, while regional differences and individual dietary preferences exist, average food costs remain relatively consistent (USDA, 2025). These relatively fixed costs underscore the disproportionate burden that rising food prices place upon families least able to absorb them, and which are only further exacerbated by grocery taxes in certain jurisdictions.

Mississippi offers a striking example of the regressive nature of grocery sales taxes and the disproportionate burden they place on those least able to afford them. As noted above, Mississippi not only had the highest percentage of monthly household expenditures spent on food but also imposed the highest grocery tax in the nation until July 1, 2025, when the rate was reduced to 5%, making it the second highest. Thus, the same family of four indicated above at the lowest food tier would pay an additional $920.64 and $1,396.08 a year at the highest tier at a grocery tax of 7% (the state’s full sales tax no matter the product). Under the now reduced 5% grocery tax rate, the same family would still pay $657.60 in taxes at the lowest food tier and additional $997.20 per year at the highest tier (USDA, 2025). Especially telling—and consistent with the burden imposed by a regressive tax like those on groceries—is the fact that Mississippi has the lowest median household income in 2025, at $44,966 a year (World Population Review, n.d.). Conversely, even a financially struggling family of four in California--despite the state’s highest sales tax—would not face this additional government burden from grocery taxes, regardless of the USDA food tier selected, given California exempts groceries.

The Impact on Families of Grocery Tax Elimination in States Since 2020

The elimination of grocery taxes since 2020 has been especially instructive as to how working families can be favorably impacted. As noted, the repeal of state grocery taxes has gained traction over the last decade or so, even across states in which their respective leaders may not share similar political

ideologies. The most recent example occurred during the recent one-year grocery tax holiday in Illinois, during which taxpayers saved a cumulative $360 million (Sharkey & Josko, 2023). The governor’s stated reason for implementing the tax holiday during Fiscal Year 2023 was to provide relief from rampant food inflation. A poll conducted as the holiday ended found that 70% supported permanently repealing the state’s grocery tax, in the wake of grocery prices rising 5.8% over the same 12-month period (Sharkey & Josko, 2023). The governor reiterated the ongoing burden of food inflation and the successful relief that the tax holiday provided working families when he proposed repealing the grocery tax permanently the following year (Pritzker, 2024). Yet, Illinois is not alone. The following table lists the states that have repealed or reduced their grocery taxes since the beginning of the decade, along with the actual or projected first-year savings for taxpayers. Note that projected data is used in cases where repeals have been approved but data is not yet available.

Table 3

First-Year Savings from Recent Grocery Tax Cuts

| State | Grocery Tax Repeal or Reduction |

Year of Grocery Tax Repeal or Reduction |

Cumulative Savings for Taxpayers (First Year, millions) |

Lost Grocery Tax Revenue as % of State Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | Repeal | 2026 | $10.9 | 0.168% |

| Illinois | Repeal | 2026 | $325 | 0.400% |

| Kansas | Repeal | 2025 | $156 | 0.600% |

| Mississippi | Reduction | 2025 | $127 | 1.628% |

| Oklahoma | Repeal | 2024 | $418 | 3.325% |

| Virginia | Repeal | 2023 | $399 | 0.456% |

Note: Data from Meadows, 2025[17].

One of the most compelling takeaways from Table 3 is that while the revenue lost from eliminating grocery taxes makes up only a small portion of state budgets, the savings for working families are meaningful and immediate. In Missouri, for example, repealing the grocery tax would save taxpayers an estimated $60 per week, or about $259.80 in an average month. As one supporter testified, “Sixty dollars may, to a lot of people, not sound like a lot of money… But $60 could be two weeks’ worth of gas money for me to get to my job, or it could be the copay for a doctor’s appointment, or new shoes” (Meadows, 2025). What is an arguably minor loss to governments can be a major benefit to low-income families. The growing momentum to repeal grocery taxes again reflects both the regressive nature of the tax and the relief its removal provides.

Funding the Elimination of the Grocery Tax

Support for repealing state grocery taxes has expanded across party lines, driven by concerns over the tax’s disproportionate impact on lower-income households and its limited importance to state budgets. However, to offset the lost revenue, states have often relied upon budget cuts or alternative funding sources. While eliminating the grocery tax is a positive step, not all states have filled the gap in ways that consistently benefit the very taxpayers the policy was intended to help.

Debates over tax cuts reveal a fundamental divide about the purpose of government. Critics claim that revenue reductions threaten essential services, but this position presupposes government efficiency and the effectiveness of government programs and services. In reality, programs without a profit motive face little pressure to spend wisely or streamline operations. and the money they spend belongs to taxpayers, not the state. Tax cuts, then, are not acts of generosity but restoration to the taxpayers of what is, in the first instance, their own.

This proposal begins from a different premise: that unchecked government growth and the taxes sustaining it weigh heavily on citizens. True fiscal responsibility means shrinking waste and bureaucracy, not shifting taxes elsewhere or piling on debt. By that measure, Illinois offers the wrong model. Its repeal of the grocery tax was a step in the right direction, but it was undermined by the decision to let localities reimpose the same tax to fund municipal projects and initiatives (Feurer, 2023). Rather, the proposal maintains that the loss of grocery tax revenue should prompt officials and citizens to reassess priorities and practice greater fiscal discipline.

Conversely, Arkansas, which is also due to sunset its grocery tax on January 1, 2026, demonstrated a fiscally responsible approach that encouraged government agencies that were dependent on the state’s grocery tax to make up lost revenue with more efficient operations. Arkansas’ state grocery tax funds outdoor recreation and tourism departments, as well as wildlife and nature preservation programs. In Fiscal Year 2027 (the first full fiscal year of the grocery tax repeal’s enactment), it is expected to cost the state $10.9 million (Grajeda, 2025a). For context, the state’s enacted Fiscal Year 2026 budget totals $6.49 billion, making the projected revenue loss approximately 1.7% of the total budget. Assuming moderate budget growth in Fiscal Year 2027, the relative impact of the repealed grocery tax revenue will decline (Grajeda, 2025b).

Lawmakers did not find the need to “pay for” these cuts by reappropriating funds or cutting other programs. Rather, by relying on the efficiently operated agencies that were the beneficiaries of this tax, these agencies used their surpluses to absorb the loss of grocery tax subsidies, essentially buying down the grocery tax with their excess funds. For example, the Division of Arkansas Heritage received $950,000 in Fiscal Year 2025 and had a budget of $51 million. Responding to the impending cuts, the director attested to the Division’s capacity to absorb the $950,000 loss (Brawner, 2025). Upon approval of the grocery tax repeal, Gov. Sanders confidently affirmed the reality that surpluses and efficiently run agencies made this tax repeal possible, saying, “These agencies have very healthy, strong budgets, [I’m] very confident in their ability to continue to do what we’ve been doing, which is breaking tourism records” (Grajeda, 2025a).

Unlike Illinois, Arkansas did not shift the grocery tax burden to local governments. Instead, it used the resulting revenue reduction to shrink the overall size of government. Rejecting the impulse to treat surpluses as an excuse for higher spending, the state eliminated the grocery tax outright and required agencies to absorb the loss. Conversely, Illinois’s approach will leave taxpayers vulnerable to uneven and regressive future reimpositions of the grocery tax by their local jurisdictions, which are now free to do so. By relying on the strong financial health and operational efficiency of its agencies, Arkansas managed to sunset the grocery tax without resorting to backfilling funds and, thus, offers a model of responsibly eliminating a state grocery tax that also delivers meaningful reform in the form of lower taxes and a movement toward the overall reduction of government.

South Dakota as a Case Study in Addressing Concerns for Funding Grocery Tax Elimination

Not every state has been successful in repealing its grocery tax. Attempts to repeal South Dakota’s grocery tax have repeatedly failed: first in 2004 by voter initiative, then in 2023 in the state legislature, and again in 2024, also by voter initiative (Keene, 2024; Whitney, 2023). Each attempt was soundly defeated by overwhelming margins. While discouraging, these failures serve as cautionary tales, offering valuable lessons on how other states that are considering grocery tax repeals can address common counterarguments and strategic missteps to better position their proposals for success. Indeed, the state’s two most recent failures are most instructive.

For the state’s 2023 legislative session, then-Governor Kristi Noem strongly advocated for the state legislature to repeal the state grocery tax, which is taxed at the state’s standard sales tax rate. Indeed, she campaigned on what would have represented an approximately $102 million tax cut. Noem argued that the tax cut could be covered by budget surpluses, but Republican legislators primarily objected to missing the opportunity to use these surpluses “in favor of strategic investments before enacting a tax cut,” pointing to such things as increasing teacher pay. While the bill failed in committee 8-1, the state passed a reduction in the general sales tax from 4.5% to 4.2%, where it stands today. The governor’s Bureau of Finance and Management estimated that this tax cut represented a savings of $0.30 on a $100 grocery bill (Huber, 2023).

Attempts to repeal the grocery tax by voter initiative in 2024 proved even more difficult. Critics cited Initiated Measure 28’s exemption of “anything made for human consumption” from sales tax, which they considered overly broad (Initiated Measure 28, 2024). The crux of this definition, while allowing the state to continue taxing alcohol and prepared food, would exempt such things as CBD products, toiletries, over-the-counter drugs, and tobacco (which would compromise the settlement the state made with tobacco companies for state costs mitigating the effects of smoking). Instead of a narrow tax cut on the essential food items families need to survive, the broad definition risked exempting even novelty and recreational items, potentially leading to unforeseen revenue loss and potential legal complications (South Dakota Searchlight, n.d.).

Both failures represent different ways in which advocates for repealing state grocery taxes can fail to understand the implications of their proposals. The 2023 legislation represented a fundamental difference in premises about tax revenue and lawmakers’ approach to stewarding public funds. Despite having budget surpluses that could have offset the cost of repealing the grocery tax and provided relief to working families, even Republican lawmakers chose to expand state spending instead. Their decision to use surpluses for new projects, rather than tax relief, squandered a rare chance to reduce the burden of government without affecting current spending.

In both the 2023 legislative effort and the 2024 ballot initiative, a lack of strategic alignment, whether with legislative values or voter skepticism, proved fatal. Advocates misunderstood both the political dynamics within the legislature and the fiscal implications of the initiative’s language. In both cases, the proposals were misaligned with the concerns of legislators and voters alike. In the future, effective attempts at eliminating the grocery tax will require better political coalition-building and more precise policy language. These shifts would help to develop messaging that resonates with both lawmakers and the public. Proposals should anticipate and preempt common objections by demonstrating fiscal responsibility and a clear, limited scope of any tax repeal.

Approaches to Eliminating Grocery Taxes for Relief from High Prices

In order to provide American families meaningful relief through the repeal of grocery taxes, future proposals must be advanced with greater strategic focus, avoiding the insufficient precision that doomed past efforts. This approach entails narrowly tailored tax relief directed at essential grocery items, framed within the broader context of comprehensive fiscal reform.

1. Address Concerns by Affirming that Non-Essential Goods Will Not be Affected by Grocery Tax Repeals

The decisive defeat of South Dakota’s Initiated Measure 28 and the legislative rejection of repeal efforts in 2023 underscore the need for a more disciplined approach. Future proposals must both double down on the premise that tax revenue belongs to those that generated these funds and acknowledge that these same citizens value certain state services funded by taxes, such as education. Proposals to eliminate the grocery tax should remain focused on food staples and avoid broad definitions of exempt items.

2. Reform Structural Spending and Improve Government Efficiency to Offset Revenue Losses

To address concerns that repealing the grocery tax may merely shift the burden onto other forms of taxation, advocates must reassure taxpayers that surplus revenues can and should be prioritized to ease the financial burden on citizens without necessitating other tax increases. States ought to repeal their grocery taxes using existing budget surpluses and agency savings rather than raising other taxes or cutting essential programs. Following the model of Arkansas, which used surpluses within its own agencies to eliminate the grocery tax, the plan argues that states can make similar repeals while improving government efficiency and accountability. By requiring agencies to operate more efficiently and by prioritizing surplus revenues for tax relief, the proposal aims to lower the overall tax burden on citizens and reduce the size and cost of state government. Ultimately, this policy proposal can and should bring needed relief to citizens seize the opportunity to lessen the government’s burden.

3. Remove Taxes on Essential Food and Grocery Items at Both the State and Local Level

The approach by which each state eliminates grocery taxes is as important as the repeals themselves. Unlike Illinois, states considering repeal should prohibit local jurisdictions from reimposing grocery taxes altogether. Ideally, such legislation would also prevent municipalities from substituting other taxes to recoup lost revenue, compelling them instead to adapt through the kinds of efficiency and cost-cutting measures outlined in Section 2 above.

Conclusion

The existence of grocery taxes in periods of elevated food prices represents an avoidable and regressive burden on working families. As the experience of states such as Illinois and Arkansas demonstrate, repeal provides immediate, measurable relief that voters strongly support, and it can be achieved in both Republican- and Democrat-led jurisdictions. The most effective and durable way to repeal grocery taxes is to use the process to improve government efficiency and create lasting tax relief for families.

While concerns over revenue loss are not insignificant, they must be weighed against the fundamental principle that governments should not tax essential goods that no household can easily forgo. Still, these concerns about revenue loss and funding of essential services must be addressed to ease the passage of future grocery tax repeals. Grocery tax repeals must be focused on the essential food staples on which families depend, and should omit recreational items such as alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco-derived products. Further, to ensure that tax relief is meaningful and lasting, states must not permit local jurisdictions to enact their own grocery taxes. With food costs continuing to outpace overall inflation and public frustration over the cost of living shaping the national political landscape, state leaders have both the fiscal means and the moral imperative to act.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The above table compares the retail prices of essential food staples in January 2020—two months prior to the officially declared COVID-19 emergency—and in January 2025, when the Biden Administration ended. The data highlights the lasting effects of that period’s policy responses and events on the cost of everyday groceries. Note that the data represent unadjusted prices, excluding seasonal trends.

[2] The above chart highlights the relative increase in the all-food CPI compared to the overall all-items CPI and other key index components, underscoring the disproportionate impact of inflation on food prices.

[3] Mississippi taxed groceries at the full sales tax rate of 7% until July 1, 2025 when the tax on groceries was reduced to 5% (Office of Governor Tate Reeves, 2025).

[4] The chart above lists the 11 states that currently impose a sales tax on groceries, with the term groceries defined according to each individual state’s tax code, including the taxes of Arkansas and Illinois which will sunset January 1, 2026. It does not include additional rates which might be imposed by local jurisdictions which can sometimes be more than double the base state tax rate, thus greatly increasing the tax burden on the consumer.

[7] Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), 2024.

[8] Ill. Governor’s Office, 2025.

[10] Kan. Legis., S.B. 125, 2025

[12] Office of Governor Tate Reeves, 2024

[17] This table highlights the financial impact of recent grocery tax repeals or reductions across several states. For each, it shows the cumulative savings for taxpayers in the first fiscal year of implementation. The fourth column shows the diminished revenue due to the repeal of the grocery tax as a percentage of the state budget the year it was enacted. The data used represents actual savings realized by residents in the first year or projected savings where data is not yet available.

Resources