Designing Education Savings Account Programs to Maximize Education Freedom

Key Takeaways

« Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) allow parents to customize their child's education across multiple providers and services.

« Universal eligibility is critical. Programs open to all students encourage the creation of new learning models and builds the needed coalition for long-term success.

« ESAs represent the gold standard in school choice policy, but getting the details right ensures that all K-12 children in a state can access genuine educational freedom.

introduction & Background

Education savings accounts, also known as education scholarship accounts, permit families to exit the traditional public school system and assume control over how and where their child learns. When a parent uses an ESA, a portion of the funds their local district would have received from the state for the student is deposited into a private account that is controlled by the parent and monitored by the state or an approved entity. Parents are then empowered to redeploy their own tax dollars on a combination of tuition, tutoring, homeschooling materials, specialized therapies, and other state-approved educational expenses. Because ESAs allow families to combine multiple categories of spending, they have significantly more potential than the conventional school voucher.

Vouchers, pioneered in Milwaukee in 1990 (Rouse, 1998) and currently available in 15 states (EdChoice, 2025, p. 69), can be used only for private school tuition. ESAs are more flexible and parent-friendly, allowing families to allocate some funds for tuition, some funds for tutoring, and the remainder for online courses or workforce training, for example. In some states, unspent ESA funds may be saved for higher education. This flexibility is a principal reason why ESAs are the gold standard for state-level school choice. Whereas vouchers must be spent entirely on full-time private school (which blunts a school’s incentive to control tuition), ESAs encourage families to weigh prices and quality, prompting schools and education providers to offer affordable learning opportunities.

Legislators crafting ESAs face several design questions, which are asked and answered in this issue brief. This paper is intended for states that are creating new programs or strengthening existing ones. Above all else, decisions about student eligibility determine whether ESAs will work best. Programs that are too small and restricted to select populations rarely develop the support needed to endure, while universal, well-funded ESAs become more resilient.

A Brief History of ESAs

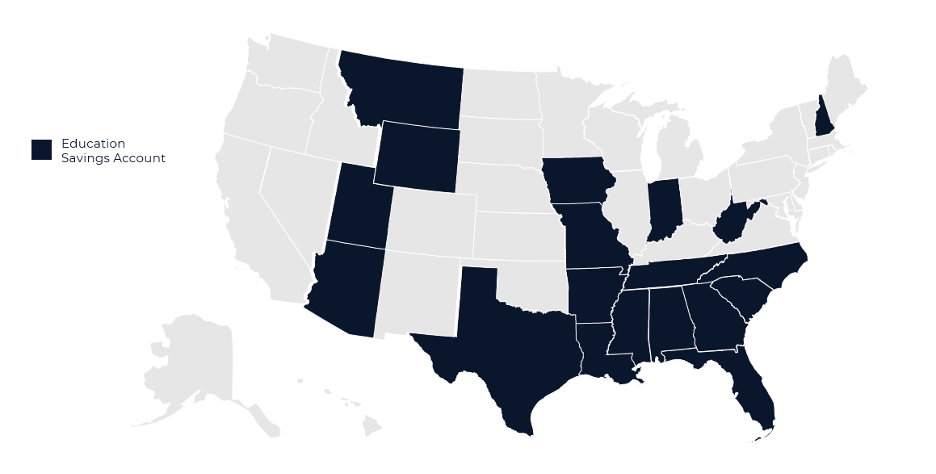

The ESA concept was first proposed by Dan Lips (2005) and first enacted in Arizona in 2011. Florida followed in 2014, then Mississippi and Tennessee in 2015, and then North Carolina in 2017 (EdChoice, 2025, p. 21). These initial programs were highly targeted, typically serving students with special needs who had previously enrolled in traditional public schools. Early results were promising: families reported high satisfaction (Bedrick & Butcher, 2013), encouraging early adopter states to expand eligibility and inspiring other legislatures to introduce ESA bills. Yet growth remained modest. From 2011 to 2020, only five states enacted ESA programs.

Figure 1

States with ESA Program

Note. Data from The ABCs of School Choice (p. 9) by EdChoice, 2025 (https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2026-ABCs.pdf) and the author’s research.

After 2020, perhaps sparked by impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, adoption accelerated sharply, with 13 states creating ESAs between 2021 and 2025 (EdChoice, 2025). These newer programs were more ambitious, moving beyond narrow eligibility criteria to serve broader populations. Legislators responded to parental demand fueled by pandemic-era learning loss (Malkus, 2024), as well as to rising concerns about progressive ideological excesses in district schools (Greene & Paul, 2022). ESAs were no longer limited to students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) or to those assigned to low-performing schools. Instead, they were becoming a mechanism for delivering education freedom to all K-12 students.

In 2021, West Virginia enacted the first near-universal ESA (McElhinny, 2021), and Arizona responded a year later by expanding its trailblazing program to serve all students (Beienburg, 2022). As of this writing, ESAs are available in 19 states (America First Policy Institute, 2024) and have emerged as the leading state-level school choice mechanism (see Figure 1). Importantly, states are abandoning small, population-specific programs in favor of universal policies that allow all students to participate regardless of income, disability status, residence, or prior enrollment. The shift reflects a simple but essential goal: to provide all children with the opportunity to pursue an education aligned to their needs and family values.

The following sections of this issue brief provide policy recommendations on the most consequential elements of ESA design, drawing on lessons from states that have already navigated these important choices.

Which students should qualify for an ESa?

Every K-12 student in the state. ESAs should be available regardless of income, special education status, or prior public school enrollment. And all qualifying students should be guaranteed funding.

The first iteration of private school choice programs—meaning vouchers, tax-credit scholarships, and ESAs enacted between 1990 and 2015—restricted eligibility to specific student populations, with the intent of demonstrating proof of concept and attracting enough bipartisan support to eventually expand the population of eligible students. The strategy, though reasonable at the time, ultimately proved unsuccessful at scaling up eligibility to a large swath of American families. By 2020, few states had robust choice environments, and Democratic lawmakers repeatedly failed to secure the votes needed for passage, even when programs were limited to sympathetic subgroups (Greene & Paul, 2021). Education freedom advocates changed tactics after 2020, capitalizing on prolonged school closures and progressive ideological excesses to push for universally available education choice bills (Greene et al., 2021). This strategic shift was immediately successful, with twice as many ESA programs enacted between 2021 and 2023 than in all prior years combined. States should continue building on this strategy, creating and expanding programs to serve all students.

Universal eligibility strengthens a state's educational marketplace. When student eligibility is broad, education entrepreneurs receive a signal that demand will be scalable. New schools and learning environments can enter the market and grow with confidence. Targeted programs, on the other hand, send muted signals to providers and ultimately limit the supply. With less supply, families have fewer quality, affordable options.

It's important to define what is meant by universal. A state’s program is truly universal only if every student is eligible for an ESA and if every qualifying student is guaranteed funding (Tarnowski & Ritter, 2025). This distinction matters, as several states passed programs that appear to be available to all students but lack sufficient funding to provide ESAs to every child who applies (Tarnowski, 2024). As of this writing, the only ESA programs that are universal in eligibility and funding are Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, New Hampshire, and West Virginia.

ESAs often benefit state budgets (Lueken, 2024), which is another why reason lawmakers should embrace maximum eligibility with guaranteed funding. ESA students exit the traditional public school system, so states that are funding ESAs are simply redirecting dollars that those students would have otherwise received. At worst, this is budget neutral. What’s more, ESAs have historically been funded below per-pupil revenue averages in district schools (i.e., 75% of per-pupil funding), creating additional fiscal room. Relative to specialized population programs, universal programs minimize administrative burdens and compliance costs for state agencies. Limiting participation based on student characteristics requires agencies to check family income, review disability documentation, and verify prior public school enrollment—all of which can lead to errors and application denials that frustrate families (Hui, 2024; Jones, 2025).

If truly universal programs are not politically feasible, then states can phase in eligibility over time. West Virginia's Hope Scholarship and Arkansas's LEARNS Act followed this approach, as both of these programs sunset prior public school eligibility requirements after a few ramp-up years.

How much funding should an esa provide?

Lawmakers should fund ESAs with all public dollars that would have otherwise been provided to the participating student if he or she were enrolled in a traditional public school.

States have a compelling interest in raising public dollars to fund K-12 education, but there is no compelling interest in restricting those dollars to traditional public schools. A well-designed ESA program puts funding directly into the hands of parents, with guardrails and accountability, recognizing that parents can make the best decisions on behalf of their children.

The amount of funding that states deposit into ESAs varies and largely reflects local school funding norms. States that spend more on traditional public schools generally allocate more to their ESAs. On average, ESAs provide $6,000 to $10,000 annually per student (EdChoice, 2025, pp. 22-58). This typically includes all state revenue, some local revenue, and little to no federal revenue.

Rather than aiming for an arbitrary funding target (e.g., $5,000, $7,500, or $10,000), states should fund ESAs competitively with the per-pupil revenue allocated to traditional public schools. If ESA programs are underfunded, non-traditional educational providers cannot compete on equal footing with traditional public schools, which receive substantially more revenue through categorical grants, federal funds, and tax-supported or debt-financed capital projects. When ESA students exit the district school system, states can redirect operational dollars that would have otherwise been spent on those students. Capital funding is more complicated to reallocate, but should be shared equally to allow schools of choice to effectively compete in the long term. The goal should be to empower families to find the best option for their children, not to preserve revenue streams in the very public systems that families are seeking to leave.

Students with disabilities who participate in ESAs should receive supplemental funding consistent with the state's special education formula. Texas' ESA, for example, provides students with up to $30,000, informed by what the state’s special education funding formula would have allocated to that child (Texas Education Freedom Accounts, n.d.).

How should states allocate funding into the ESA?

ESAs should be funded through a state's per pupil funding formula.

Legislators face a fundamental decision between automatic formula funding and annual appropriation. Choosing between these options shapes whether an ESA delivers universal access or remains constrained by annual budget negotiations. A formula-funded program can grow to meet demand, while appropriated funding leaves the ESA vulnerable to shifts in political winds. Formula funding gives service providers confidence to enter and expand. Arkansas, Florida, and West Virginia have adopted formula-funded ESA programs that are most capable of meeting parental demand.

Although stable, formula-based funding allows ESAs to be truly universal, several states have enacted programs that are funded through appropriation. The examples below show the practical difficulties ESAs face when designed without formula-based funding:

- Louisiana’s ESA, established in 2024, relies on annual appropriation. In the program’s second year, the governor requested $94 million to fund new applicants, but a faction of lawmakers preferred to redirect $50 million of the requested ESA funding toward unbudgeted stipends for public school teachers (McKendry, 2025). Ultimately, only 800 out of 39,000 new applicants received scholarships, and the rest were consigned to a waitlist (Bedrick, 2025b; Maringy, 2025).

- In 2023, North Carolina passed a large ESA expansion, but the program remained funded through annual appropriation. One year later, 55,000 unfunded students applied for the program, culminating in parents rallying at the state capitol building, urging the Legislature to clear the waitlist (Bass, 2024). Fortunately, lawmakers approved new funds for the program (Levesque, 2024b), but uncertainty remains about whether funding will keep pace with future demand.

- Utah annually appropriates a set amount of funding toward its ESA, thereby limiting the number of scholarships awarded and ensuring that some families end up on waitlists. In the program’s first year, 10,000 students were awarded scholarships out of 27,270 who applied (Gilbert, 2024).

- In 2025, Alabama officials were surprised by the amount of parental demand in the first year of its ESA program and had to propose an additional funding allocation (Crain, 2025).

ESAs can also be funded by tax credit-eligible donations to approved nonprofits, which in turn distribute and administer scholarships to eligible students. The tax credit approach, although suboptimal because it relies on donor interest, can serve as an alternative when formula funding is politically infeasible. Tax credit ESAs are perhaps most viable in states with constitutional restrictions against school choice programs. Since tax credit programs are privately funded, they may be less susceptible to legal challenges from education freedom opponents (Bedrick et al., 2016).

What expenses should an ESA cover?

Families should have maximum flexibility to spend funds on tuition, homeschooling materials, special education therapies, tutoring, online learning, and a range of other educational costs.

ESAs were always intended to be more flexible than vouchers. Accordingly, parents should be empowered to spend ESA funds on a wide range of educational options, not just private school tuition. Recall that traditional public schools routinely spend public funds on transportation, special education therapies, field trips, curricular materials, and other contracted services. ESA families deserve the same latitude, and when lawmakers craft ESAs, they should include a broad range of allowable expenses and service providers. If a school district can spend education revenue on a particular expense, so too should ESA families.

Florida follows this approach, permitting families to use funding on the following: K-12 private school tuition and fees; instructional materials; curricula; postsecondary tuition and fees; testing fees; contracted public school services; tutoring; educational therapies; homeschooling expenses; summer education fees; after-school education fees; and certain prekindergarten tuition and fees (The Family Empowerment Scholarship Program, 2023, Sec. 1002.394). Arizona's program is similarly comprehensive. ESA funds can be used for the following: K-12 private school tuition or fees; textbooks; educational therapies, paraprofessionals or educational aides; tuition for vocational and life skills education; assistive technology; tutoring; curricula; online learning; testing fees; postsecondary tuition and fees; contracted public school services; and school uniforms (Arizona Empowerment Scholarship Accounts, 2011, Sec 15-2402).

Should TESTING BE REQUIRED FOR ESA students?

ESA students should not be required to take state tests administered by public schools.

Lawmakers seeking to expand freedom and flexibility in education should apply the same principles to testing requirements. If ESA participants are forced to take the same public school accountability tests, non-public schools and service providers will likely start teaching to those tests, thus undermining education freedom and innovation. Private schools, homeschools, and other providers need flexibility to innovate without pressure to align instruction to public school pedagogy, values, and standards. Backdoor curricular mandates could push private schools to opt out of the program altogether. Research from Florida’s education sector shows that private schools were 46% less likely to participate in choice programs when faced with the prospect of mandatory state testing (DeAngelis et al., 2019).

Parents who favor nontraditional learning environments care about test scores (Watson & Lee, 2025), but they want assessments that make sense for their school's approach. ESA programs could therefore require some form of testing without mandating any particular assessment (Tate, 2024). In other words, states should permit ESA families and participating schools to choose from a menu of nationally recognized, norm-referenced tests and require that those results are reported to parents and stakeholders at the school or program level. (Parents should be permitted to request their student take state tests, if they wish). This way, education providers have the freedom to build curriculum around their mission while still being accountable to parents for student achievement. Lawmakers can also direct state agencies to conduct regular parent surveys to gauge satisfaction with the ESA program and learn about areas for improvement.

Should States Require ACCREDITATION OR CERTIFICATION OF participating schools and Education service providers?

No, states should encourage new educational options by minimizing barriers to entry.

The primary goal of an ESA program is to increase the supply of alternative learning options. When parents, as consumers, can direct how education dollars are spent, new learning models will emerge and compete based on quality and value. To fully realize this supply-side expansion, states must avoid mandatory accreditation or certification standards on schools and providers. Top-down accreditation and state certification requirements have not been successful at improving quality in traditional public schools, and applying these same requirements to ESA providers will stifle the very innovation that educational freedom programs are meant to encourage. Instead of making private schools jump through bureaucratic hoops or satisfy accreditors, states should trust parents to decide which educational providers deserve their money.

West Virginia is a model state when it comes to encouraging new educational models (Hope Scholarship Program, 2021/2024, Sec.18-31). The Mountain State’s ESA statute simply requires that an education service provider submit notice that it wishes to participate in the program and certify that it will not discriminate with respect race, color, or national origin. There are no requirements for accreditation.

On the other end of the spectrum, these states include certain barriers to entry for schools and instructors:

- Georgia requires all participating private schools to be accredited or in the process of becoming accredited (Georgia Education Savings Authority, 2025).

- Florida requires that tuition and fees for part-time tutoring services be provided by individuals who are traditionally certified, which significantly limits the pool of high-quality instructors who can mentor ESA students (The Family Empowerment Scholarship Program, 2023, Sec. 1002.394).

- Texas requires participating private schools to be accredited and to have been in operation for at least two years (Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, n.d.). Attempting to ensure that parents choose among quality options may be well-intended, but these requirements make it harder for new schools to get off the ground.

What State Agency should Manage the ESA Program?

The State Treasurer, Comptroller, or a similar finance-oriented agency should handle this role.

One of the most important policy decisions is selecting the state agency to be the program administrator. Oftentimes, the best choice is not the Department of Education. State Education Agencies (SEAs) specialize in following federal rules and creating their own rules for districts to follow, neither of which has much to do with managing an ESA. Further, there is a risk that SEAs might run the program in ways that undermine education freedom, given their close ties to the traditional public education system.

Financial agencies like the State Treasurer or Comptroller are better positioned for this role because they already know how to distribute funds, oversee payment platforms, and audit accounts. Unlike SEAs which are most responsive to the needs of the traditional public school system, financial agencies are primarily focused on managing funds efficiently. Whatever agency ends up in charge, states need to staff it with people who understand and support parental choice in education.

Contracting with nonprofit organizations to support program administration can make the program run more smoothly for parents. For example, Florida contracts with Step Up For Students to handle application review, vendor management, and payment processing for its ESA program (Levesque, 2024a; Step Up for Students, n.d.). Texas will use a similar approach, with the Comptroller of Public Accounts serving as the agency manager and Certified Educational Assistance Organizations (nonprofits) handling day-to-day administration (Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, 2025). States that engage with nonprofit organizations or other vendors to support the ESA administration should competitively bid the opportunity through a transparent process.

How should States Audit ESA Spending?

States must strike a balance between fraud prevention and convenience for participating parents.

Critics of education freedom warn that letting parents control education dollars will lead to fraud (Hroncich, 2025), but the experience in Arizona tells a different story. As the first state to enact ESAs and now home to one of the largest programs in the country, Arizona has a track record of empowering parents while limiting fraud. A recent audit uncovered potential fraud or misuse in less than one-tenth of 1% of all Arizona ESA spending (Bedrick, 2025b). An earlier review in 2018 found less than 1% of purchases were made from unauthorized vendors (Bedrick, 2024).

Most ESA programs use online platforms where parents shop from a closed marketplace of approved vendors (ClassWallet, 2021). These digital wallets are better than reimbursement models that force parents to outlay cash on the front end. Digital wallets can lower the risk of fraudulent purchases by giving parents access to curated lists of vetted providers and products (Odyssey, n.d.). Because everything listed in the marketplace is already approved, parents can make purchases without having to wait for paperwork to clear.

Parents in West Virginia’s ESA program use a digital wallet that, in addition to providing access to pre-approved items and vendors, also allows them to request new items. When parents submit these new requests, a machine-learning model performs an initial eligibility review (Hope Scholarship, 2025). Items flagged as potentially unallowable are either removed from the parent’s shopping cart or sent to a human reviewer for manual approval. In the future, states should continue exploring artificial intelligence tools to screen and process routine payments automatically, thus reducing staff time spent manually reviewing each transaction (Chartier, 2023). States should also implement risk-based auditing, which is an approach that focuses oversight on transactions and accounts that are most likely to have problems.

Any case of fraud, no matter how small, becomes a talking point for ESA opponents (Hendrie, 2023). It should therefore be a top priority for supporters of education freedom to keep ESA programs clean and functioning as intended. When bad actors are identified—be it parents or providers—they should be removed from the program and prosecuted when warranted. But isolated incidents should not sink programs that are working well for hundreds of thousands of families, and lawmakers should steel their spines against bad-faith criticism along these lines.

Should Unused ESA Funds Revert to the State?

No. Unused ESA funds should roll over annually and remain in parents’ accounts for future allowable K-12 or higher education expenses.

Reverting dollars to state governments sends a “use-it-or-lose-it” signal to parents that lawmakers should seek to avoid. Alternatively, allowing parents to keep unused balances in their ESA incentivizes responsible budgeting and prevents inefficient spending at the end of a school year. Permitting funds to roll over can also help moderate tuition inflation at participating private schools. A study by Bedrick, Greene, and Burke from the Heritage Foundation (2023) found that states with school choice policies (such as ESAs) experienced 7% lower private school tuition inflation relative to states without school choice. Empowering parents with the control to direct education spending and encouraging them to plan for expenses is an important step toward creating a better-functioning education marketplace.

Several states permit ESA funds to roll over annually. Some, like Florida, even allow unspent balances after 12th grade to be used on postsecondary expenses (The Family Empowerment Scholarship Program, 2023, Sec. 1002.394). Conversely, Alabama's ESA does not allow funds to roll over and reverts unused dollars back to state coffers (Griesbach, 2025). In the future, states should allow contributions to 529 savings accounts as an allowable expense under the ESA program.

conclusion

Education Savings Accounts offer states a path to transform K–12 education by placing parents, not bureaucrats, at the center of decision-making. When every education dollar follows students to the environments where they learn best, families gain real power to choose among providers, and a healthy form of free-market competition emerges. That competition drives schools and service providers to improve quality, expand access, and innovate in ways that a centralized system simply cannot replicate.

States that adopt universal eligibility, stable formula-based funding, broad allowable uses, limited regulatory barriers, flexible assessment options, and modern oversight mechanisms create conditions where education entrepreneurs can enter the market and families can select what works for their children. When parents are empowered and providers compete to serve them, students benefit. With strong policy design and unwavering commitment to education freedom, ESAs can become the cornerstone of a more dynamic, responsive, and innovative education system—one that delivers better outcomes and greater opportunity for every child.

Resources