Federal Education Tax Credit: Policy Roadmap for States

Key Takeaways

« A new federal initiative offers individuals up to $1,700 in dollar-for-dollar tax credits for contributions to Scholarship Granting Organizations, which fund a range of educational expenses for K-12 students across the country.

« States must affirmatively elect to participate in the tax credit. If a governor refuses, another authorized state actor can make the election.

« The simplest and most important step for states is to formally elect to participate—as soon as possible—so that SGOs have time to organize and solicit qualified donations.

« States with pre-existing education choice programs can align them to mirror the structure of the federal tax credit, which would maximize education freedom.

Introduction

The federal scholarship tax credit—also known as the federal education freedom tax credit—created in the Working Families Tax Cut Act (WFTCA) gives states a tremendous opportunity to expand educational freedom (H.R. 1, 2025). The law allows taxpayers to claim up to $1,700 in dollar-for-dollar federal tax credits for contributions to nonprofit Scholarship Granting Organizations (SGOs).

Thanks to the WFTCA, American taxpayers have a choice: send up to $1,700 to fund the federal government or redirect that $1,700 to an SGO that funds scholarships covering a range of K-12 educational expenses, including private school tuition and homeschooling (26 U.S.C. Sec. 25F, 2025). This is the first time the federal government has established a tax credit incentivizing scholarships for K-12 students—a historic step toward school choice for every student in every state (Donalds, 2025a).

Although taxpayers everywhere can begin making tax credit-eligible gifts in 2027, SGOs can only provide scholarships to students in states whose governors affirmatively opt-in to the program.

States that opt in will see donations support local students, while states that decline to opt in will see donations flow across state lines. Consider the example of Wisconsin, where the governor signaled that he will not participate (Beck, 2025). Wisconsin taxpayers can still make donations and claim the credit, but donations must be sent to SGOs in other participating states. Fortunately for students across America, Wisconsin is likely to be an outlier, as governors in Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas have already indicated they will opt in—and more are expected to follow (Bruenlin, 2025; Office of Governor Kim Reynolds, 2026; Exec. Order No. 25-14, 2025; Dausch, 2025; Schultz, 2025; Office of the Texas Governor, 2025).

Public support for participation is strong, according to a recent national poll: 71% of registered voters want their governor to opt in to the credit (Napolitan News, 2026). Among respondents with school-aged children at home, 78% say they are likely to apply for a scholarship if given the chance.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) have created a process for states and the District of Columbia to make an advance election to participate in the tax credit (Internal Revenue Service, 2025). Governors can simply submit Form 15714 to the IRS, allowing SGOs to distribute scholarships in 2027 (Donalds, 2025b).

The Treasury will propose regulations related to this tax credit in Summer 2026 (Donalds & Paul, 2025c). While some state legislative sessions will begin (and perhaps end) before these regulations are finalized, there are several statutory and administrative actions states can take in advance of federal rulemaking to support a successful launch of the tax credit initiative. The simplest and most important step is for states to formally elect to participate as soon as possible so that SGOs have time to organize and solicit qualified donations.

History

Efforts to create a federal school choice program span nearly three decades, but nothing became law until the federal tax credit in WFTCA. The Family Education Freedom Act, first introduced in 1997 and re-introduced in every Congress through 2011, proposed an individual tax credit for education-related expenses (H.R. 1816, 1998; H.R. 935, 2000; H.R. 368, 2001; H.R. 612, 2003; H.R. 406, 2005; H.R. 1056, 2007; H.R. 1951, 2009; H.R. 954, 2011). The 2014 Scholarships for Kids Act took a different approach, allowing federal funds earmarked for low-income students to cover private school tuition and other state-sanctioned educational providers (S. 1968, 2014). None of these efforts were signed into law.

During his 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump supported a $20 billion school choice initiative (Sullivan, 2016). Once in office, President Trump tasked Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos with developing a federal school choice program. DeVos’ plan became the Education Freedom Scholarships and Opportunity Act (EFS), introduced in 2019, which proposed a federal tax credit for private donations to SGOs (S. 634, 2019). EFS allowed individuals and corporations to claim the credit, capped at 10% of the donor’s adjusted gross income and $5 billion nationwide for contributions to SGOs.[1] Although EFS was not signed into law, it became the framework for future efforts.

The 2022 Educational Choice for Children Act (ECCA) improved on EFS by eliminating the state opt-in provision, preventing governors from restricting scholarships to be used at certain schools, and adding an escalator provision to annually increase the availability of credits (Blew et al., 2025). Congress reintroduced ECCA in 2024 (Todd-Smith & Butch, 2025), and the House Ways and Means Committee passed a streamlined version before the Fall election. In May 2025, the House passed a reconciliation bill that included the federal education tax credit. The Senate amended the proposal, finally settling on a 100% tax credit for individual taxpayers, with a per-donor cap of $1,700 (Blew et al., 2025). President Trump signed the bill into law, establishing the nation’s first federal scholarship tax credit.

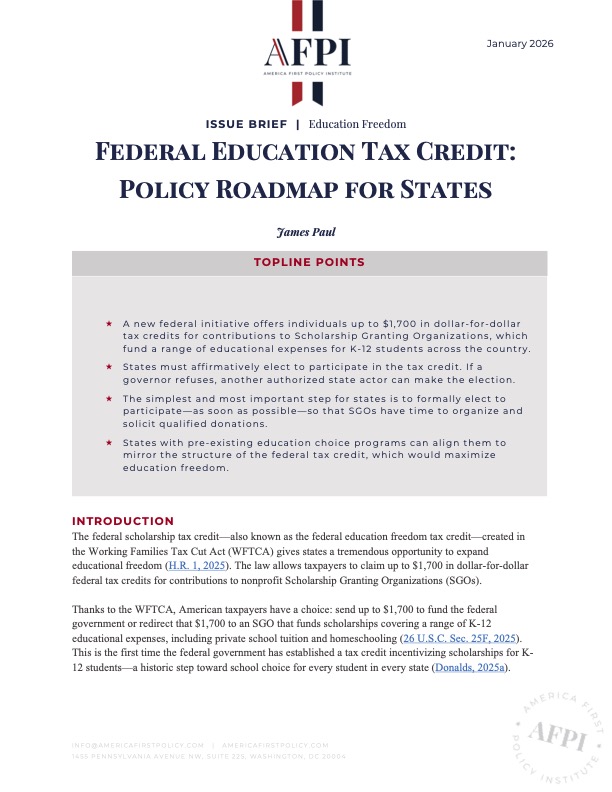

While federal school choice eventually passed after decades of effort, states have historically moved faster, enacting dozens of private school choice programs during the same period (see Figure 1; America First Policy Institute, 2024). These programs fall into several categories:

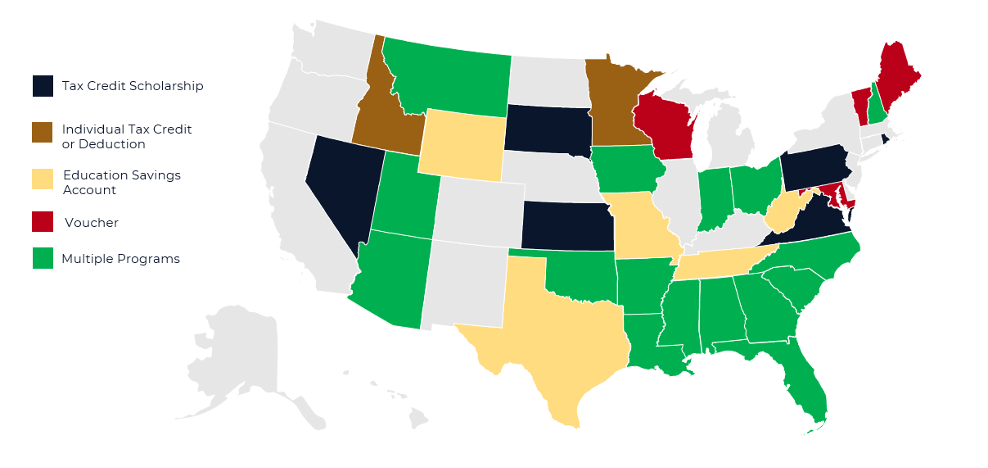

- Tax-credit scholarships currently operate in 17 states (see Figure 2). Individuals or businesses donate to an approved SGO in exchange for a credit against their state taxes. The SGO then awards scholarships to children, which are most frequently used for private school tuition. This model inspired the federal tax credit established in the WFTCA. States set their own rules with respect to student eligibility, donation limits, and tax-credit amounts.

- Education savings accounts (ESAs), also called education scholarship accounts, deposit a portion of state education funding into parent-controlled accounts that are monitored by the state. Parents direct this funding toward a range of approved expenses, such as private school tuition, online courses, tutoring, homeschooling, and educational therapies for students with special needs.

- Vouchers are state-funded scholarships that families use for private school tuition. Milwaukee piloted the nation’s first voucher program in 1990 (Rouse, 1998). Unlike ESAs, vouchers typically only cover private school tuition.

- Individual tax credits and deductions let parents reduce their tax liability based on their educational expenses incurred. Depending on program design, parents either claim a credit that lowers their tax bill or claim a deduction that reduces their taxable income. Unlike the three programs described above, parents must front the costs and wait until they file taxes to claim credits or deductions.

Figure 1

States with Existing Private School Choice Programs

Note. Data from The ABCs of School Choice (p. 9) by EdChoice, 2025 (https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2026-ABCs.pdf) and the author’s research.

Figure 2

States with Tax Credit Scholarships

Note. Data from The ABCs of School Choice (p. 21) by EdChoice, 2025 (https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/2026-ABCs.pdf) and the author’s research.

Federal tax credit: Recommendations for all states

In Summer 2026, the Treasury is expected to issue regulations for participating states. Until then, states should consider the following actions to align with the expected outlines of the federal tax credit. If any conflict emerges between these recommendations and final federal rules, the federal rules will prevail.

- Governors should opt in to the credit by submitting the Advance Election to Participate Under Section 25F for 2027 (Form 15714).

- Adopt the broadest income limits and qualified expenses allowed by federal law.

- Permit scholarships to be used in private schools, homeschools, microschools, hybrid programs, tutoring, online programs, special education services, and any other educational setting permitted under 26 U.S.C. 530.

- Clarify that scholarship funds are intended to supplement existing educational opportunities rather than supplant state education revenue. Accordingly, states could prohibit traditional public schools from receiving scholarship funding from any student to provide any service, program, or activity for which it already received public funds.

- Federal law permits scholarships to be spent in traditional public schools, but states can limit how much money flows into those settings to preserve the supplement-not-supplant principle. For example, states could cap the maximum amount of tax-credit eligible funding that SGOs provide to students for use in traditional public schools (e.g., no more than 15% of scholarship funds disbursed in any calendar year).

- If permitted by Treasury/IRS, states should submit updated lists of participating SGOs multiple times per year, especially during 2027, to ensure the maximum number of SGOs can participate as they are established and prepare to distribute scholarships.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR states where the governor has not YET opted in

The WFTCA provides that the election to participate is made by “the Governor of the State or by such other individual, agency, or entity as is designated under State law to make such elections on behalf of the State with respect to Federal tax benefits” (26 U.S.C. Sec. 25F, 2025). If the governor declines to opt in, taxpayers in that state can still claim the federal credit, but their donations will be sent to SGOs in other jurisdictions. States should act to prevent this outcome.

- Assign the opt-in authority to another state official. Legislatures can authorize the Treasurer, Auditor, Comptroller, or even itself to make the election.

- Establish a contingency rule stating that if a governor does not opt in by the time regulations are published by Treasury/IRS, another designated authority is empowered to make the election on behalf of the state.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR states with existing choice programs

States already offering private school choice—be it through ESAs, vouchers, or state-level tax credit scholarships—should consider how current programs will interact with the new scholarships funded by federal tax credit-eligible donations. Many existing state programs provide less per-pupil funding than net public school expenditures, and the new federal tax credit can reduce those disparities. States can also harmonize eligibility rules to reduce confusion for families and education providers.

- Explicitly allow SGOs to provide “top-up scholarships” for students already receiving an ESA, voucher, or state tax credit scholarship. Many state school choice programs do not cover full tuition at a nonpublic school, so combined awards should be encouraged. By using federal scholarships to top up existing programs, states create a fair environment where public schools, private schools, and other learning models compete on equal footing.

- If an existing program limits eligibility by income, states should raise the program’s income threshold to match the federal tax credit limit, which is 300% of the area median gross income. This term refers to the income limits published in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Income Limits Documentation System.

- State revenue agencies should prepare to prevent tax credit double counting. Donors should not receive a state tax benefit for the same contribution that qualifies for a 100% federal tax credit.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR states without existing choice programs

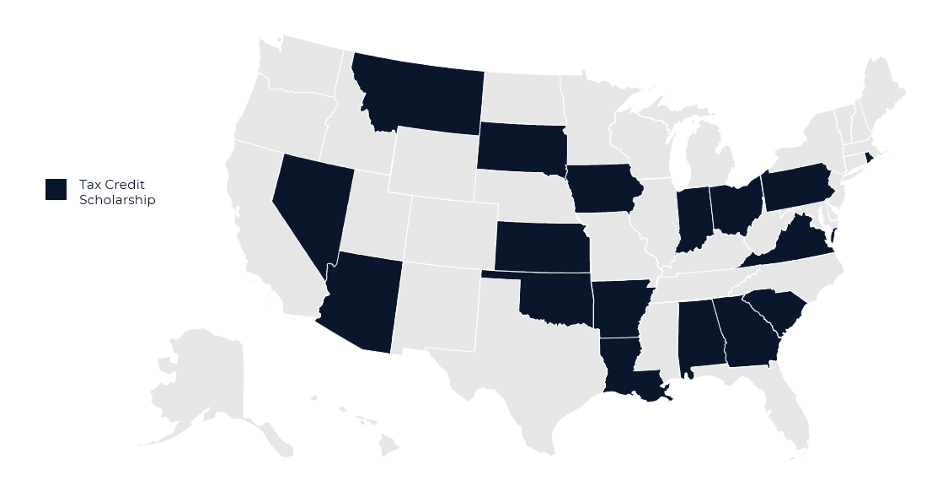

States without existing school choice infrastructure can use the federal tax credit as a springboard for new programs. States that opt in to the federal credit could offer an additional state credit, such as up to $5,000 per taxpayer, for contributions to in-state SGOs. Under this hypothetical, a taxpayer could contribute $6,700 to an SGO and receive a $1,700 federal credit plus a $5,000 state credit. States may choose a lower credit value than 100% to address fiscal concerns, but a full dollar-for-dollar tax credit is most likely to spur transformative gifts to SGOs.

Figure 3 illustrates the hypothetical example of Illinois creating a parallel state-level tax credit.[2] In this example, Illinois passes legislation to permit individual taxpayers to claim up to $2,500 (and for married filing jointly couples, up to $5,000) in dollar-for-dollar state tax credits for contributions to SGOs that appear on Illinois’ state list. Figure 3 shows the tax consequences for a family with $150,000 in household income across three scenarios. In scenario 1, the family makes no charitable donation and sees about $115,000 in take-home pay. In scenario 2, the family makes a $6,700 donation to a traditional nonprofit charity and claims a federal tax deduction, which lowers both take-home pay and taxes paid.[3] In scenario 3, however, the family makes a $6,700 donation to an eligible SGO on Illinois’ list and receives a $1,700 federal tax credit along with a $5,000 state tax credit. Here, the family retains the same $115,000 take-home pay but significantly reduces its taxes paid at both the state and federal levels, relative to scenario 1. The family also has a higher income retained in scenario 3 relative to scenario 2.

Figure 3

Hypothetical Example: Comparative Impact of Charitable Giving on Taxes and Income

Note. This figure presents simplified tax scenarios for an Illinois family with a $150,000 income, assuming standard deductions and no additional tax complications. Calculations use 2025 married filing jointly federal tax brackets, Illinois’ 4.95% flat income tax rate, and 7.65% FICA taxes. Actual outcomes will vary depending on individual tax situations.

CONCLUSION

This issue brief provides recommendations that are flexible enough to support states with governors who are inclined to opt in, states with governors who are not, and states with or without existing school choice programs. States should consider these legislative and administrative steps to support a meaningful expansion of education freedom.

Appendix: Implementation Framework

States Recommended For |

Policy Recommendation |

Action Required |

All States |

Governors should take administrative action opting into the credit. |

Governors fill out Form 15714. |

States where the governor has opted in or is likely to opt in |

Adopt the broadest income limits and qualified expenses allowed by federal law. Permit scholarships to be used in private schools, homeschools, microschools, hybrid programs, tutoring, online programs, special education services, and any other educational setting permitted under 26 U.S.C. 530. |

No legislation is required, but states should be vigilant about legislative or regulatory efforts to limit student eligibility or the types of eligible expenses. |

Clarify that scholarship funds are intended to supplement existing educational opportunities rather than supplant state education revenue. |

Pass legislation prohibiting traditional public schools from receiving scholarship funding from any student to provide any service, program, or activity for which it already received public funds. |

|

Maximize the number of SGOs that distribute scholarships and give SGOs sufficient time to solicit tax credit-eligible donations. |

Pending forthcoming guidance from Treasury, states should prepare to submit lists of participating SGOs to Treasury multiple times per year, especially during 2027. |

|

States where the governor has NOT opted in, or is unlikely to opt in |

Assign the opt in authority to another state official. |

Pass legislation authorizing the Treasurer, Auditor, Comptroller, or the Legislature itself to make the opt-in election. |

States with existing private school choice programs [ESAs, tax credit scholarships, vouchers] |

Explicitly allow SGOs to provide “top-up scholarships” for students already receiving an ESA, voucher, or state tax credit scholarship. |

Pass legislation clarifying that SGOs may award scholarships to supplement existing choice programs. |

If an existing school choice program limits eligibility by income, states should raise the income threshold to match the federal tax credit program limit, which is 300% of the area median gross income (AMGI), or, more preferably, eliminate the income limitation altogether. |

Pass legislation amending existing programs to eliminate the income threshold or increase student eligibility income threshold to 300% AMGI. |

|

Prevent taxpayers from claiming duplicative state and federal tax credits for the same contribution. |

State revenue agencies update tax forms and audit procedures to prevent tax-credit double counting. |

|

States without existing private school choice programs |

Create a parallel state-level tax credit that mirrors federal rules. |

Pass legislation enacting a state-level tax credit, aligned with federal rules, that further incentivizes contributions to SGOs in a state. See Figure 3. |

Works Cited